AI-juiced political microtargeting

Reasonable People #53 looking carefully at the claims in one study which uses generative AI to customise ads to personality type

Come with me on an interrogation of this recent paper - The persuasive effects of political microtargeting in the age of generative artificial intelligence - Simchon, Edwards & Lewandowsky (2024).

(This post is too long for some email readers, so if you have this in your inbox you may need to click the header to see the whole thing)

Claims:

Recent technological advancements, involving generative AI and personality inference from consumed text, can potentially create a highly scalable “manipulation machine” that targets individuals based on their unique vulnerabilities without requiring human input. This paper presents four studies examining the effectiveness of this putative “manipulation machine.” The results demonstrate that personalized political ads tailored to individuals’ personalities are more effective than nonpersonalized ads (studies 1a and 1b). Additionally, we showcase the feasibility of automatically generating and validating these personalized ads on a large scale (studies 2a and 2b).

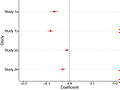

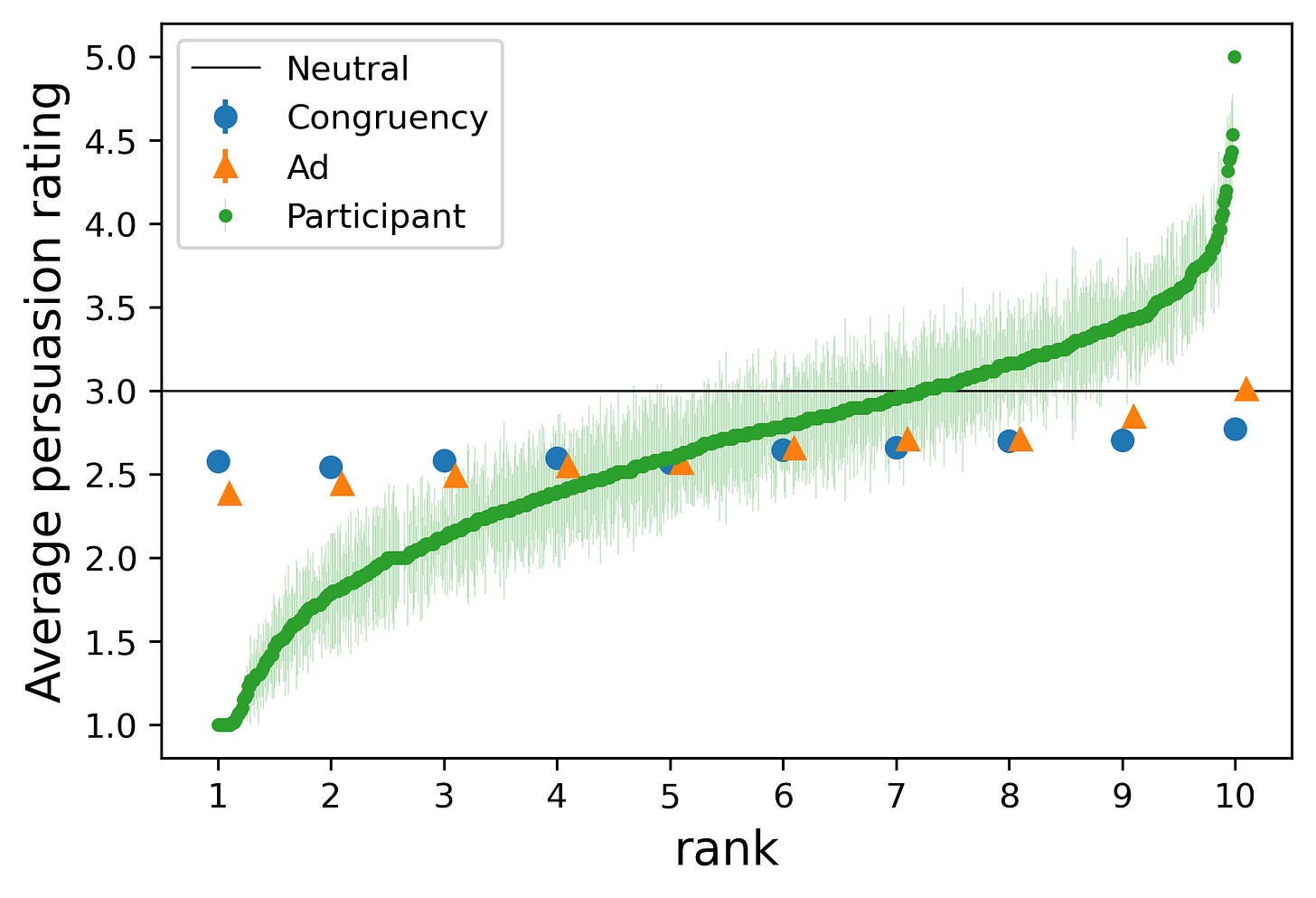

The key results are summarised in their Figure 1,. which which shows the importance personality matching in predicting persuasion, for the analyses they ran, in each of their four studies.

When you’re assessing an experiment, it’s always instructive to look at what a study actually showed, and what they actually measured, and compare these with what the claim. That’s what I’ll do here. But first…

A preliminary endorsement

Along with the published paper, supplementary appendices are also available, also the full set of materials used, as well as all data and analysis code. This is an example of best practice without which the kind of review I’m about to present wouldn’t be possible, and for which the authors deserve credit.

While, in what I write below, I question the interpretation the authors put on their results, in the course of reviewing the results I became convinced of the accuracy of the report and the high standards which the governed the conduct of the research. My critical comments should be read in this context.

Stimuli

The paper frames the idea of a “manipulation machine” within the familiar context of Brexit (UK) and Trump (US) and the involvement of targetting firm Cambridge Analytica in both. The paper describes the ads as “political ads that were published on Facebook to UK users between December 2019 and December 2021”. Given this, I was expecting Political ads with a capital P: ads from parties, probably, or at least electoral campaign ads.

Here’s ad 1 (of 10) from studies 1a and 1b:

Far more innocuous than the Brexit/Trump/Cambridge Analytica framing suggests. To be fair, some are a bit more spicy. But not much:

Aside from the “small p” political nature of the ads and their topics, they are- to my eye - pretty bland. They are hard to have strong feelings about either for or against, and so don’t obviously seem suitable for tests of psychological targetting.

Here’s the advert rated most persuasive by participants in experiment 1b:

Outcome variable

Now let’s look at what the study actually measured. The measures were ratings of perceived persuasiveness. Here are the six questions in full, for each advert participants rated each one on a 1 to 5 scale from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”

“I find this ad to be persuasive”

“This is an effective ad”

“I would click on this link after seeing this ad”

“Overall, I like this ad”

“This ad has made me more interested in the topic”

“I am interested in learning more about this topic after seeing this ad”.

There is some difference between participants’ perceptions of whether an ad is persuasive and if it actually persuades them to change their behaviour (e.g. their voting). The authors defend the choice of outcome variable in this way…

our focus is on endorsement of ideas and ideologies. In this attitudinal playing field, self-reports have a strong track record in microtargeted persuasion (15, 19). A meta analysis revealed a reliable link between self-reported persuasion and measures of attitudes or intentions ( r = 0.41) (20), confirming the appropriateness of perceived persuasion ratings for our research.

The unstated part of the justification for using this outcome measure is that measuring real-behaviour is just so challenging. Nobody will claim that self-reported attitudes are perfect measures of persuasion, but the practicalities of experimentation mean you are often left with the imperfect proxy outcomes rather than the true measure (like voting behaviour) which you want to theorise about.

For this study, let’s leave it is as the study measures persuasion in a way that means the authors can legitimately claim to have evidence of persuasion, but we - dear readers - may also have legitimate doubts about how strong the generalisations from this evidence can be.

Effect size

The first two studies of the paper simply take the 10 adverts, after assessing them a score for the personality dimension “openness”, show them to participants, who rate them on the items listed above. The targeting part is that each participant also does a short personality quiz, so has their own score for openness. This means each ad x participant combination has a “personality matching” score, and it is the effectiveness of this in predicting the outcome measure that is shown in Figure 1.

The analysis used to produce the result - a regression - is fundamentally a statistical model which takes variation in the input and output variables and tries to predict one from the other. This has a couple of consequences. First the results depend on the observed variation. It isn’t obvious, for example, that results general to adverts in a different range of persuasiveness (although they may).

Second, the size of the effect reported by the model can be hard to interpret. It is fundamentally a relation between changes in the predictor (in this case “personality matching” ) and output (persuasiveness rating).

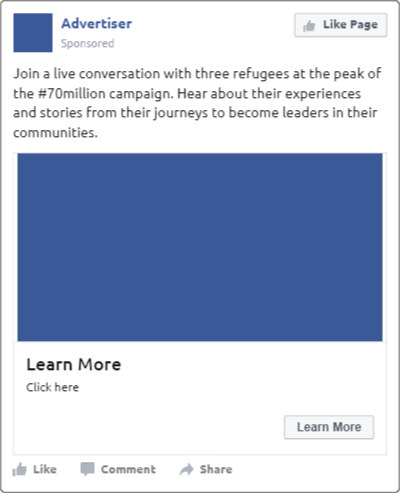

To get handle how both of these elements, I replotted the data from study 1b (again, kudos to the authors for sharing, which made this possible).

For the first plot, I made two series. The first is every advert, in order of average persuasiveness rating (from lowest to highest - in the plot, orange triangles). For the second series I took every participant x advert interaction and categorised them into ten equally sized bins based on persuasiveness rating (from lowest to highest - in the plot, blue circles).

The hope is that the plot shows the variation which the different factors produce in persuasiveness (i.e. the raw material which the analysis is trying to explain):

A few of things leap out at me from this plot

most ads rating by most people as *not* persuasive. The neutral point on the scale is a 3 (neither agree not disagree with the statement), and the average rating is ~2.6 (so on average participants slightly disagreed that the ads were persuasive, or they liked it, or whatever).

you can see the effect the main claim of the paper rests on in the slope of the blue ‘congruency’ points: as the personality match variable increases, so do participant’s average rating of the ads.

there is more variation due to differences between ads than due to differences in congruency/personality matching.

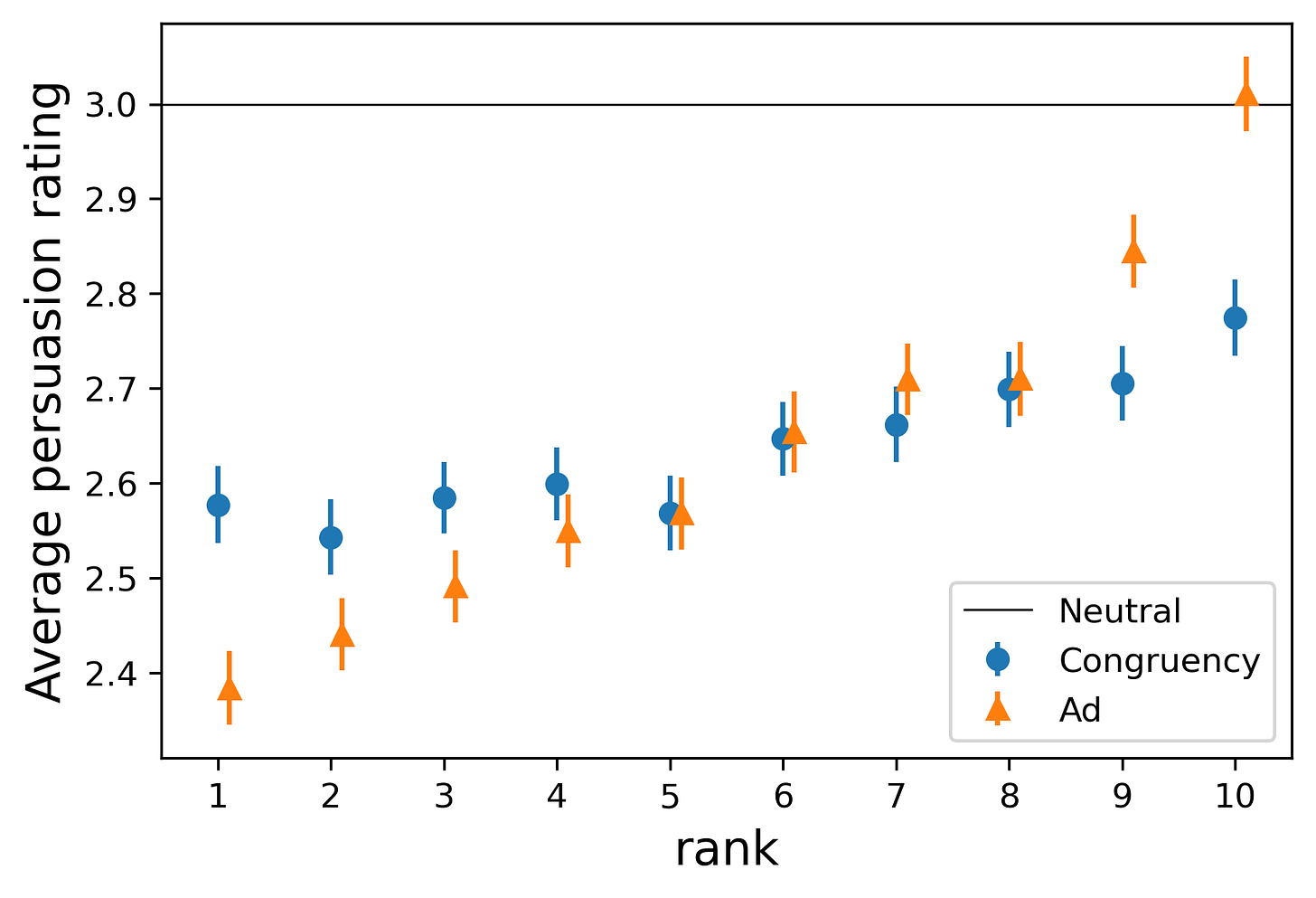

The relative lack of variation can be put into context if we replot the figure using the full scale from 1 (“strong disagree”) to 5 (“strongly agree”), and add a series which shows the average persuasion rating given by each participant (from lowest to highest - in the plot, green points. Also because there are 803 participants they should be ranked 1st to 803rd, but I’ve scaled it so it fits with the other bins, 1 to 10).

From this from I take

much bigger variation between participants than between adverts

a bunch of participants have average ratings of 1 (bottom left of the curve), meaning they gave every advert a score of 1 on every question. Thanks guys, what did you even get paid for?!

but for the most part participants have managed to spread themselves evenly over the totally available space of “persuadedness”.

Conclusions

What to make of this?

On the one hand, we’ve some dull ads, rated as unpersuasive and non-interesting by participants. Research using these doesn’t seem a good fit to the “hot” political microtargeting of “unique vulnerabilities” which the reader is invited to imagine by the paper introduction.

On the other hand, notice how my hesitations about the sheer dullness of the stimuli undercut hesitations about the size of the effect produced: if personality matching meant participants were more likely to give higher ratings to these adverts, isn’t it possible that for more engaging adverts - ones with more personality, in that sense - would shift the dial more strongly?

I say, yes, it does. For all the flaws of a weak outcome measure and uninspiring stimuli, I think the study shows that personality matching - in the way measured here - could predict greater persuasiveness of adverts.

However, I think it also shows at the same time, that there are bigger differences between adverts due to other factors than between well and badly matched adverts (my replotted first figure). My take away would be that it is probably more effective to design better adverts, rather than better targetted adverts.

Additionally, my second figure suggests that the really big differences are between people, and due to factors other than captured by personality variables. This supports the efficacy of finding the people that are already engaged and persuaded by your material - a well established campaign tactic more akin to mobilisation than persuasion.

Context is everything

Linking to this paper in a piece in The Conversation, one coauthor (Stephen Lewandowsky) writes “A recent paper illustrated how large language models can be deployed to craft micro-targeted ads at scale, estimating that for every 100,000 individuals targeted, at least several thousand can be persuaded.”

It isn’t clear how they get to this statistics from the paper published, but it is undoubtedly true, that - to the extent you believe the paper shows a genuine persuasive effect - it shows a marginal effect of N out of 100,000 people effected (or 100,000 people all effected N% maybe). Whether N is 1 in 100,000 or 10,000 in 100,000 doesn’t matter much. Given the uncertainties of the experiment you couldn’t claim either with much certainty.

What the summary leaves out is what the persuasive effect is. “At least several thousand can be persuaded that an advert is slightly less terrible” would be more accurate. And it leaves out that the other factors which the experiment shows may be more important (“Thousands more were persuaded more by different ads rather than the ones targeteds for them”).

Reviewing the study left me convinced the effect reported is reliable - the study is thoroughly done - but also that the authors have read more into it than I would have.

Context for the context

This study and The Conversation piece by coauthor Lewandowsky are part of a wider discussion about misinformation, and how it should be characterised and how serious it is a threat. Dan Williams, whose comment on an earlier newsletter, led me to look at this paper, has set out a number of warnings about over interpreting results like the one I’ve reviewed today (start here?). He’s one of a number of skeptical voices which are the target of this recently published rebuttal : Why Misinformation Must Not Be Ignored (Ecker, Tay, Roozenbeek, Cook, Oreskes, Lewandowsky, 2024). I’ll review that next time, for now I’ll say that the claims in this kind of review - and where any of us put ourselves in these debates - depend on the careful reading of evidence like the study I’ve just walked through.

References

Simchon, A., Edwards, M., & Lewandowsky, S. (2024). The persuasive effects of political microtargeting in the age of generative artificial intelligence. PNAS nexus, 3(2), pgae035. https://doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgae035

Data & code: https://osf.io/5w3ct/

The Conversation: Disinformation threatens global elections – here’s how to fight back

Ecker, U. K. H., Tay, L. Q., Roozenbeek, J., Linden, S., Cook, J., Oreskes, N., & Lewandowsky, S. (2024, March 4). Why Misinformation Must Not Be Ignored. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/8a6cj

Last time:

RP #52 Propaganda is dangerous, but not because it is persuasive, in which I put out my list of non-persuasion functions of propaganda:

Phil Feldman made a good suggestion, that propaganda also serves to build narratives, and that the existence of narratives (and sources of narrative confirmation) serve to bring people into your sphere of influence (out keep them out of other people’s). This seems like an important thought. I had a worry at the time of writing that there is an aspect “grand narrative” aspect of propaganda which I wasn’t capturing, and Phil’s comment opened my mind to the idea that there are, in turn, reasons you want to build narratives, using propaganda or other means (and, really, at the limits, isn’t one person’s propaganda another person’s comms strategy?). Thanks Phil!

The (lack of) success of Nazi propaganda: update

Also last time I linked to a study - “Nazi indoctrination and anti-Semitic beliefs in Germany” (Voigtländer & Voth, 2015) - what has had been recruited to argue that Nazi propaganda was not that successful. The key result was that antisemitism was higher among those who went to school during the Nazi era - a success for Nazi indoctrination, but not, it was argued, for radio or print propaganda.

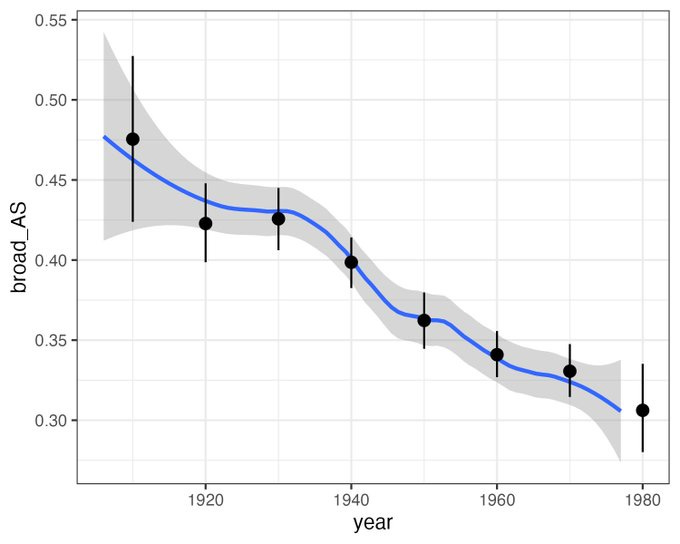

Two weeks ago, Alexander Bor ran his own re-analysis of some of the same source data that Voigtländer & Voth, 2015 used. The re-analysis questions the basis for there being any indications of a success of antisemitic Nazi indoctrination: Bor’s reanalysis shows a continuous decline in antisemitic attitudes against birth year

If you *squint* you might argue that the Nazi era coincides with pause in the decrease in antisemitism, but not more than this (the prior paper argued there was a bump for those born in the late 20s and 30s relative to those born before or after).

And finally…

Zach Weinersmith: https://www.smbc-comics.com/comic/caveman

END

Comments? Feedback? Personality matching? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online