Across The Red Line

Reasonable People #19 a radio show about listening to your ideological opponent's reasons made me listen to my ideological opponent's reasons...and I liked it.

Nobody is persuaded, nobody has their mind changed. Perhaps the reason the discussions on Across The Red Line are so engaging is that these things aren’t the point.

Across The Red Line is a BBC Radio 4 production which takes two people with diametrically opposed views on some issue, and brings them into dialogue with the chair (Anne McElvoy) and an expert in conflict resolution (Gabrielle Rifkind or Louisa Weinstein).

The first episode I listened to spelled out at the beginning that the point of the discussion was not to persuade or change minds, but to help each other understand the opposing point of view. The point is not even to reach some agreement or consensus, explained the Rifkind, but to reach a better understanding of the person who disagrees with you. The method is to focus on finding shared values and experiences, not exchanging arguments.

All I can say at this point is that it works. This prescription may not sound revolutionary, but the experience of listening was so different from most radio debates, where - once the smoke has cleared - everyone is as entrenched as ever, including me. Despite each side lobbing argument after argument, nobody is persuaded and nobody has their mind changed.

One of the guests on that first episode I listened to was a figure that I personally find despicable. If you had asked me before listening I would have said that I find this person, and their faction, intellectually glib and strategically duplicitous, with a history of advocating for irresponsible and inconsistent positions.

Our Blessed Homeland, by Tom Gauld

But the programme left me softened, if not actually charmed. The guest I thought I despised came across as sincere, thoughtful and with a set of views informed by personal experience and moral conviction. Things which almost certainly wouldn’t have come across in an adversarial debate (and which I had certainly never picked up on from previous media appearances).

After an initial statement of views, the show has a segment where the guests are encouraged to ask each other about the values and experiences which inform their beliefs. What happened to them in their lives that made them think this way? Listening to this, I was struck by the overlap with the recipe for intimacy published by Arthue Aron and colleagues in their 1997 paper The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings.

Aron’s procedure uses a series of questions which encourage ‘escalating, reciprocal, personal self-disclosure’. Starting with ‘Given the choice of anyone in the world, whom would you want as a dinner guest?’ (#1), through ‘How do you feel about your relationship with your mother?’ (#24) to ‘Share a personal problem and ask your partner’s advice on how he or she might handle it. Also, ask your partner to reflect back to you how you seem to be feeling about the problem you have chosen.’ (#36). (The full list is here if you want to try it).

I note that Aron’s procedure worked worked regardless of whether pairs were matched according to their agreement or disagreement on an issue (study 2).

The programme ends with asking the participants to swop chairs and put into words their counterpart’s position. The counterpart then gets to comment on whether they’ve been fairly represented. This is a form of the Ideological Turing Test.

The original Turing Test is a measure of an artificial intelligence’s ability to masquerade as a human. The ideological Turing Test asks you to masquerade as someone you disagree with. My suspicion is that many of us couldn’t successfully represent the views of people we disagree with (which raises the question of what we’re really disagreeing on, if we don’t understand each other).

The ideological Turing Test is part of Daniel Dennett’s prescription for how to do criticism successfully, and we’ve been thinking about whether we could operationalise it to use as a test of the success of interventions which encourage open mindedness in our new EPRSC grant.

On a similar note, this study underscores the value of exercises like Across The Red Line: Exposure to Opposing Reasons Reduces Negative Impressions of Ideological Opponents.

The authors looked at polarised issues like using animals in scientific testing, standardised testing or universal healthcare (with US participants). They found that people tended to rate those with opposing views as lacking good reasons for their position, and the more strongly they felt this, the more they were also likely to rate those with opposing views as also lacking intellectual capacity (i.e. dumb) and lacking moral character (i.e. evil).

The first bit of good news is that, actually, people didn’t rate people with opposing views very highly as dumb or evil (just more so than people with supporting views). The second bit of good news is that exposing people to reasons supporting the opposing view reduced this effect.

Our results provide evidence that reasons serve a novel function distinct from persuasion, decision change, or acquiring knowledge. That is, providing opposing reasons effectively functions to reduce negative impressions of opponents.

And

This, in turn, might have the potential to make people more willing to listen to opponents and more willing to engage in genuine discussion with their opponents, which might have positive implications for compromise, fruitful deliberation, and the pursuit of a common good in a well-functioning democracy

BBC Radio 4: Across The Red Line

Aron, A., Melinat, E., Aron, E. N., Vallone, R. D., & Bator, R. J. (1997). The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(4), 363-377.

Stanley, M. (in press). Exposure to Opposing Reasons Reduces Negative Impressions of Ideological Opponents. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/w9tp2

Vaccine concerns

Previously I’ve argued that one reason people don’t trust the experts is because they don’t believe they have their best interests at heart, not because they doubt their expertise. Trust is science among the general population is going to take on terrible practical importance when a vaccine for coronavirus becomes available.

My hunch is skepticism about vaccines is driven by a more general alienation from the establishment. If you don’t trust government (and the mainstream media, and Universities, and medical authorities) then you’ve less reason to trust claims of safety for vaccines. This leaves a gap which intuitions and misinformation can fill.

Two reports which support this hunch:

#1 Trust in scientists and attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine policy: The role of perception of scientists as elitists. (study pre-registration here).

The more you perceive scientists as elites, the lower the level of trust and the less willingness to receive vaccinations. A working paper reporting an experimental manipulation of perception of scientists as elitist (but confirming previous observational research).

#2 Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation and data deficits on social media:

Narratives challenging the safety of vaccines have been perennial players in the online vaccine debate. Yet this research shows that narratives related to mistrust in the intentions of institutions and key figures surrounding vaccines are now driving as much of the online conversation and vaccine skepticism as safety concerns. This issue is compounded by the complexities and vulnerabilities of this information ecosystem. It is full of “data deficits” — situations where demand for information about a topic is high, but the supply of credible information is low — that are being exploited by bad actors.

There’s lots more in the report which I’ve only skimmed so far. One notable thing is not just that these factors which were found to be salient in online vaccine discussion - discussion of motives and data deficits around safety - but some thing which you might expect (like conspiracy theories) were less salient:

With vaccines it is important not to let hardcore anti-vaxx campaigners occupy all the rhetorical headspace. A small minority will never be persuaded, but a larger group is vaccine hesitant for legitimate reasons and can be reached with proactive, positive, communication about the benefits of vaccines.

If you want to hear what a failure of positive communication about vaccine benefits is like, please enjoy this radio segment from the BBC (November 12th at about 2 hours 10 minute) which was incredibly ill-judged. It led with a host of unfounded and badly thought reasons for vaccine hesitancy and then followed up with reasonable points from experts who were…well, reasonable, but not dynamic enough to come back from the disadvantage that this framing put them in.

Me: Why don’t we trust the experts?, also Throwing science at anti-vaxxers just makes them more hardline

First Draft report: Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation and data deficits on social media

Kossowska, M., Szwed, P., & Czarnek, G. (2020, November 12). Trust in scientists and attitudes towards vaccines and vaccine policy: The role of perception of scientists as elitists. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/xzj9f

Reasons will change your mind

Part of an occasional series where I claim that evidence of human bias and imperviousness to reasons can actually be read to show exactly the opposite.

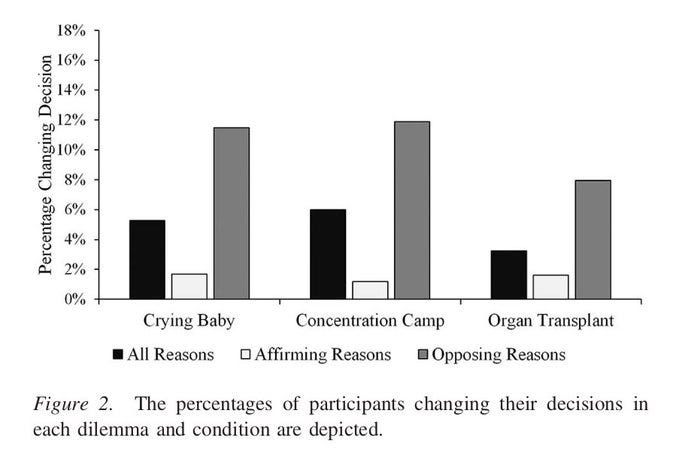

In ‘Reasons probably won’t change your mind: The role of reasons in revising moral decisions’ Stanley and colleagues gave participants tragic or ordinary moral dilemmas and asked them to choose one of the two options. They then presented them with reasons to support their original choice, reasons to oppose it, or both. Finally, they had the chance to reconsider their choice.

The authors conclude that the largest influence on people’s final choices was their initial choice, and so “reasons probably won’t change your mind”. Statistically, this is unimpeachable, but I think you can get a lot from recalibrating exactly what you would expect from hearing opposing reasons.

Here’s the results from their first study:

It looks to me like hearing opposing reasons induces judgement change at ~5 times the rate of hearing only supporting reasons. (The results are similar in their other studies.)

I’d read this as showing the power of reasons, not their impotence. The thought being that when participants make their initial choices on moral dilemmas they presumably bring to bear their total understanding - a world view, set of values, system of reasons etc. It wouldn't be madness to expect no change of judgement after listening to opposing reasons.

This from the paper abstract:

This resistance to changing moral decisions is at least partly attributable to a biased, motivated evaluation of the available reasons: participants rated the reasons supporting their initial decisions more favorably than the reasons opposing their initial decisions, regardless of the reported strategy used to make the initial decision. Overall, our results suggest that the consideration of reasons rarely induces people to change their initial decisions in moral

It seems like to accept this argument you have to make the assumption that people’s initial choices are essentially arbitrary. Maybe for a philosopher they are, since they are all dilemmas without right answers, but it is disrespectful of the participants to assume they pick an initial choice at random (and, essentially begs the question of whether our choices are guided by reasons).

I don’t accept the claim that participants used "motivated reasoning" to justify their initial choices (as shown by evaluations of argument quality being influenced by their initial judgement). If people had their own good reasons for their initial choices of course they would rate opposing reasons as lower quality. This is participants being consistent in applying their view of the world. It is a slander to call it motivated reasoning.

Stanley, M. L., Dougherty, A. M., Yang, B. W., Henne, P., & De Brigard, F. (2018). Reasons probably won’t change your mind: The role of reasons in revising moral decisions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 147(7), 962.

Propwatch

Propwatch is a media literacy organisation with a mission to help people recognise and counter misinformation. They were kind enough to ask me to record an interview about The Illusory Truth Effect and How it Works, based on this BBC Future article by me a few years ago (in turn based on an article from Lisa Fazio’s lab).

Needless to say I’ve been too self-conscious to actually watch the video, but I do remember enjoying the discussion. If you watch it, you can at least entertain yourself by trying to figure out what some of the books on my bookshelf are.

~10 minutes

And finally…

Via @tomfgoodwin

Tom, you recently asked for a paper about Wikipedia. Did you mean this one? https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.706.5770&rep=rep1&type=pdf