ChoiceEngine is an interactive essay, a sort of Choose-You-Own-Adventure about the neuroscience, psychology and philosophy of freewill. Here's the start.

This is the dilemma. We believe in order. Things happen for a reason. The universe, of which we are part, obeys causal laws. This determinism promises us an ordered world, and a comprehensible one. A world that follows natural laws without magic or deities.

And yet our feeling of being free to choose opposes this causal universe. We have the unavoidable experience of choosing. Out from the centre of our selves a choice arises, seemingly uncompelled by history. We experience ourselves as uncaused causers.

Each choice is made by us, and so it feels that it could have been made otherwise. We can’t avoid choosing, and we are compelled to believe that this choosing matters.

...

Things happen for a reason, but surely we are not mere things!

The way it works is this: you receive this text by tweeting START at the @ChoiceEngine. After each text segment you choose from a list of keywords to tweet back at the bot, triggering it to send you back the next bit of the essay you want to read.

ChoiceEngine explores the felt contradictions of freewill, both in the text and the structure. The interactive medium plays on the idea that choices are inevitable (you can't play the game without making them), but also constrained (ultimately, the choices you can make are limited by the text I’ve written).

The truth that ChoiceEngine tries to express is that the you of you - the freedom of being yourself - is generated by the choices you make, regardless of whether those choices are determined or not. You’re not free of the physics of cause and effect. You are the centre of a universe of patterns of causation, a unique nexus which has its own character and its own unpredictable future. You are the choice engine.

The project flickered into life when I was invited to give a talk at the Secular & Atheist Society at University of Sheffield, back in 2014. In preparing I made pages and pages of notes, and thought a lot of about Daniel Dennett's Elbow Room and things like the Libet experiments (where brain signals anticipating a choice appear to be detectable before the individual is conscious of making a choice).

The ideas rattled around in my brain box for a few years, until funding from The Festival of the Mind helped the project move forward in the form of ChoiceEngine. James Jeffries built the backstage gubbins which make the text a twitter bot, and Jon Cannon designed the look and feel. It was a huge privilege to work with both of these two.

When you tweet at the bot it is designed to not always reply immediately. This was a choice meant to make interacting with the bot have some of the tempo of texting with a friend - the replies come back immediately, or after five minutes, or the next day, stringing the dialogue out over a far longer stretch of time than it would take to read through the words if they were all there immediately in front of you.

Again, this bit of medium design is meant to echo the message of the text - the idea that the problem of freewill is a feeling, not a logical paradox. You cure yourself of the problem by adjusting to it, not by solving it.

But now, after four years of service, and over a thousand choosers/readers, ChoiceEngine, is being retired. A service we are using to run the bot has changed its charging scheme, so the bot will be decommissioned by the end of October.

As of the point of writing you can still enjoy it by tweeting @ChoiceEngine START, but for legacy purposes I’ve now made the full text available without you needing to navigate via the twitter bot: choice-engine-text/ STARTSTART at @ChoiceEngine

You can plot the possible paths through the essay. It looks something like this

There are 18 nodes, although no single possible path takes you through all of them. The shortest path is 5 nodes long. (Somewhere in the database is a record of all the paths walked by all the readers, awaiting some future dataviz project).

After the launch of the project I wrote a short article for New Scientist, which you can read here (“It's not an illusion, you have free will. It's just not what you think”, 3 April 2019). As well as the project launching on twitter, we had a set of live talks at the festival, (my slides are here), and we were lucky enough to be joined by Dr Helena Ifill who whipped up the interdisciplinary ferment with some thoughts on her research on gothic literature and Victorian conceptions of freewill .

The full text of the ChoiceEngine will stay up - at tomstafford.github.io/choice-engine-text - although obviously the interactive element will be missing now and you'll just have to navigate it the old fashioned way by clicking links.

For completeness, here is the complete list of contents

1: dark-wood - START HERE

2: have-map

3: philosophers

4: useless

5: determinism

6: libet1

7: libet2

8: sphexishness

9: complexity

10: chaos

11: reasons

12: intuitions

13: causation

14: expts

15: hyped

16: close

17: more

18: colophon

ChoiceEngine was written by me, Tom Stafford, built by James Jefferies (web: shedcode.co.uk, twitter: @jamesjefferies), designed by Jon Cannon (web: joncannon.co.uk, instagram: @j_o_n_c_a_n/), and funded by Festival of the Mind. Full credits here.

Full ChoiceEngine text: tomstafford.github.io/choice-engine-text/

Report: A rising tide: Strengthening public permission for climate action

A think-tank report describes a RCT of 10 different persuasive messages on the importance of climate change. You can read a summary in this post, but my summary of the summary is that messages focussed on the intrinsic importance of climate action were more effective in sustaining public support for climate action than ‘co-benefit’ messages which emphasised that acting on climate could also create jobs, provide energy security.

Here’s a summary graph.

The top three “intrinsic”messages are

Global leadership. An upbeat, patriotic narrative about what Britain has done on climate thus far, and our potential to lead the world on it going forward.

Climate impacts. The impacts of climate change are here now and will get worse if we don’t act. But it’s not too late.

Future generations. We have a duty to help younger generations avoid the worst effects of climate change.

And you can see these appear to outperform co-benefits like jobs, energy security, levelling up etc.

Akehurst summarises the findings as “messages of universal destiny or concern beat more transactional ones”. I’d have to read the methodology in detail to be convinced - RCTs are complex objects and I have enough trouble running an experiment with two conditions and getting meaningful results, so this study with ten conditions surely has more risk of issues.

The question of mechanism is also interesting. Are co-benefit messages harder to make, because you’re trying to explain two things and their connection? Is the “jobs” bit of voters minds already occupied, so there’s no room for a climate angle? Or is it that the real motivator for people is things which hit their core values - like concern for future generations - and co-benefit messages are simply too transactional to resonate with peoples’ values?

Akehurst considers these possibilities and offers this thought

I think it’s simply likely that what is happening here is a conflation of elite opinion with public opinion. Co-benefit narratives do well with politicians; they do well with activists, donors. And they do well at keeping climate relevant with journalists.

All of these audiences matter, of course, they just aren’t the same as voters. But we assume they are

Post: Strengthening public support for climate action

Full report: A rising tide: Strengthening public permission for climate action

Twitter: @SteveAkehurst

Also worth checking out is this communication professional’s critique of the concept of framing ‘Words aren't magic’. Thanks to A. for the recommendation.

Dan Olner: Jordan Peterson’s zombie climate ideas

Dan traces the intellectual currents informing Jordan Peterson’s confusion about climate change. The relevance to this newsletter is that Dan diagnoses Peterson, with a particular view of knowledge and (the impossibility of) reasoned action with roots in Hayek:

You can find Peterson’s market/knowledge views in their entirety in Hayek’s 1945 essay, The Use of Knowledge in Society: the free market is the only valid knowledge-generating mechanism, capable of coordinating all economic activity. It is supra-human: the presumption that scientific knowledge can be used to intefere with the market’s working, so the theory goes, is both profoundly ignorant of the true nature of knowledge and deeply dangerous hubris, failing to understand the limits of human minds relative to the intelligence of the market.

Post: Jordan Peterson’s zombie climate ideas

Dan is currently the recipient of Prestigious Dan Olner fellowship and is on twitter as @DanOlner

Josh Koenig: Reasonable People Can Disagree—A “Company Values” Hack

In this post from 2014, Koenig shares a thought from Chris Moody about the idea of core values - the attempt by companies to say something about what their business is about, beyond the day to day. The problem is that statements of “Company Values” often end up sounding like platitudes, they are nice but don’t are often vague, or cliched, or both. Here’s Moody’s hack for avoiding that:

try to express your values in such a way that reasonable people can disagree with them.

Koenig writes

It’s counterintuitive, but brilliant. Values help you make decisions. And not obvious decisions like “Should we behave ethically?”, but decisions that otherwise feel murky. Answers to questions like “Should I hire this person” or “When and how do I deliver bad news?”.

Values should help you cut through noise. To do that, they need an edge.

And

I’ll give you a specific example. One of [the business Koenig co-founded] Pantheon’s company values is trust, a value so obvious it could be accused of being a cliché. Who doesn’t want to work in a trusting atmosphere, to be seen as trustworthy? “Here at Pantheon we value trust.” Duh. Trust is awesome. How could anyone disagree with that?

What if you phrased it like this: “nobody is going to help you unless you ask.” Suddenly it doesn’t sound quite as rosy. Actually operating in a high-trust environment can be daunting—you’re expected to take on some gnarly problems, handle them with little to no supervision, and deliver results.

In a world of vagueness and cliche we need all the tools we can get, so I share here

Link: Reasonable People Can Disagree—A “Company Values” Hack

PODCAST: Receptiveness to Other Opinions with Julia Minson

What I like about Minson’s approach is that she explicitly orients it in contrast to “how to change minds”. She introduces the idea of “attitude conflict” which is where people object to other people’s beliefs. Obviously this doesn’t always happen (e.g. you like milk chocolate, I like dark chocolate, it’s not a biggie), but when beliefs are over important issues, affect others and there is a perceived weight of evidence (e.g. covid vaccination) I may come to think that other people’s contrary attitudes are a problem in and of themselves. This is Attitude Conflict

Against this backdrop, the idea of conversational receptiveness takes on a special importance. Am I willing to listen to others, even in presence of attitude conflict, and/or around topics where it may be a given that neither of us will change our minds? In these circumstances, changing attitudes may be a remote possibility, but it still matters how we treat each other, and whether we think the other party is morally bad or unintelligent.

It is these two - the beliefs about others -that Minson’s Conversational Receptiveness scale focusses. In this podcast Minson talks about the ideas and history behind her work.

From (the recommended) opinionsciencepodcast.com

Listen: Receptiveness to Other Opinions with Julia Minson

Related paper: Yeomans, M., Minson, J., Collins, H., Chen, F., & Gino, F. (2020). Conversational receptiveness: Improving engagement with opposing views. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 160, 131-148.

REVIEW: Information aggregation and collective intelligence beyond the wisdom of crowds

We show that in both group decision-making situations, cognitive and behavioural algorithms that capitalize on individual heterogeneity are the key for collective intelligence to emerge. These algorithms include accuracy or expertise-weighted aggregation of individual inputs and implicit or explicit coordination of cognition and behaviour towards division of labour

Kameda, T., Toyokawa, W., & Tindale, R. S. (2022). Information aggregation and collective intelligence beyond the wisdom of crowds. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1-13.

It is worth pointing out that the growing literature on effective group decision making contradicts a long tradition in political and social psychology on the madness of crowds etc. As an example of this tradition, here’s a citation-classic from Cass (“Nudge”) Sunstein:

Sunstein, C. R. (1999). The law of group polarization. University of Chicago Law School, John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper, (91).

And finally…

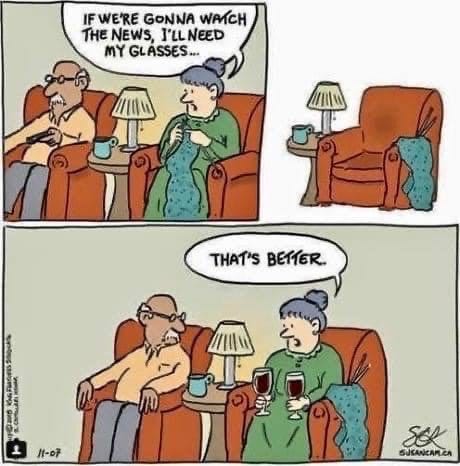

“If we’re gonna watch the news, I’ll need my glasses…" cartoon from Susan Camilleri Konar, site: susancam.ca

Comments? Feedback? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Twitter at @tomstafford

END

Hell of a lot of work you’ve put into this. Thank you.