Community Notes require a Community

How we used a novel analysis to understand what causes people to quit the widely adopted content-moderation system

Self-promotion alert - new results, but not peer-reviewed yet. Posts here are free to read, but if you like what I do please consider upgrading to paid.

Community Notes is the crowdsourced content moderation system which X pioneered. It matters because it supports engagement with facts and consensus-seeking even across lines of political polarisation.

Working with researcher Zahra Arjmandi-Lari and the fact-checker, online sleuth and author of the Indicator newsletter Alexios Mantzarlis, we analysed data on the X Community Notes system for trends in participation. The resulting preprint is titled ‘Threats to the sustainability of Community Notes on X’.

There’s no better writer on fact-checking in general than Alexios, and his latest newsletter sets out the context for why this work matters:

In January, Mark Zuckerberg (wrongly) cast Community Notes as an alternative to the fact-checking program it had built with the International Fact-Checking Network.1 With America’s governing party treating “fact-checker” as an insult, both Meta and TikTok have launched a Community Notes-like feature. YouTube has also said it is doing the same but it must be operating at such an infinitesimally small scale that it has been impossible to detect with a naked eye.

Whether as a fig leaf or a genuine effort (or a little bit of both), algorithmically-mediated crowdsourced labels are now a part of the infrastructure of major social platforms.

As the program that inspired the copycats – and the only one to share data at scale – X’s Community Notes matters disproportionately.

Here’s what we found out in our research.

He then goes on to walk through what we found. Jump over to Indicator to read all about it. Below, I want to pull out just one part of the analysis I’m particularly excited about.

The special ingredient of Community Notes is the bridging algorithm, which converts the upvotes on proposed notes into an overall helpfulness score. To get a high score - and so to be published on X - a Note needs to receive votes from across the spectrum of voters. It is not enough to receive many votes, a Note needs to receive votes from a diverse set of people.

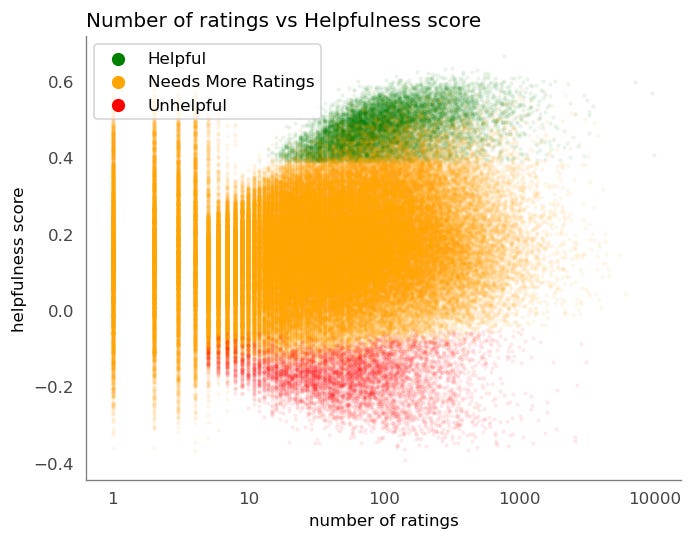

You can see this in this scatterplot. Each Note is a point, with the number of votes on the x-axis (log scale), and the helpfulness score on the y-axis. Red dots are Notes which the algorithm categorised as “unhelpful”. Green dots are Notes which the algorithm categorised as “helpful” and so published for everyone to see on X. Yellow dots represent Notes which the algorithm couldn’t categorise (because of insufficient votes of sufficient diversity).

You can clearly see the bridging algorithm at work - even notes with thousands of votes may not be published. Only Notes with a helpfulness score above 0.4 are published. (you can read more about the algorithm in my newsletter from January).

So most Notes which are written never get shown to users - over 90% in fact, and the number may be dropping. We were interested in whether this low rate is affecting users’ engagement with the system. Is there a sense in which writing Notes which never get published discourages future engagement? Does getting a Note published make it more likely an author will submit another Note to the system?

The question is a classic riddle for observational data: we see that the people who get more Notes published write more Notes, but this also works the other way around, and sounds less interesting - people who write more Notes get more notes published. The key question is “what causes what?”

To get at this, we looked at Notes from first-time authors which were just above and just below the publication threshold. The logic is that Notes here are comparable in quality and comparable in the kind of author that produces them. Some (those just above the threshold) get published, and some (those just below) don’t. We then go and look at the future behaviour of the lucky (published) and unlucky (unpublished) : do they write more Community Notes, or give up?

Fans of causal inference will recognise this as a Regression Discontinuity Design, one of a family of methods which allows some insight into what causes what when you don’t have the privilege of running experiments (experiments - which allow random assignment to different conditions - are the strongest causal inference method, but not always possible).

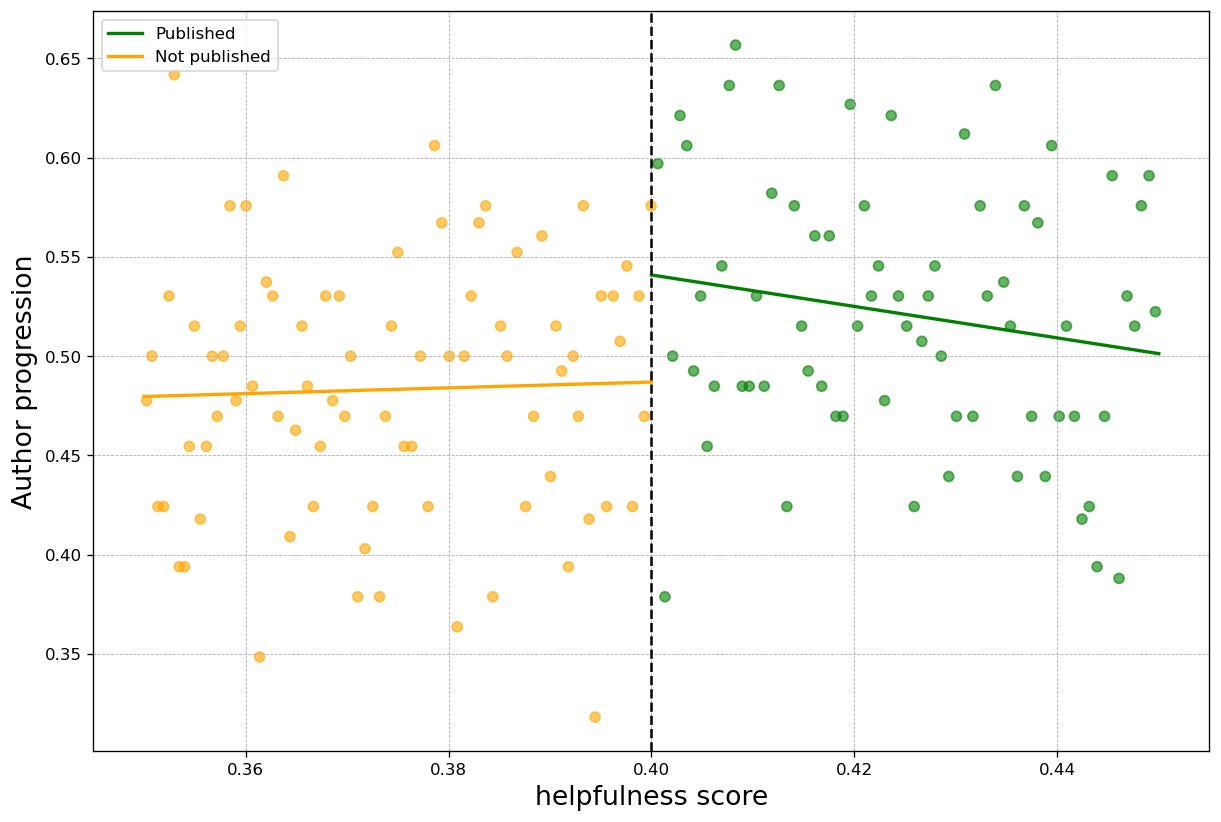

Here’s our graph of the analysis:

Note helpfulness score is on the x-axis, and the discontinuity - the 0.4 threshold for publication - is marked by the vertical dotted line. The y-axis is the measure the probability of a Note author going on to author another note. For individual authors this is either 0 (they quit and don’t author another note) or 1 (they author at least one more note). The plot shows clusters of authors (grouped by the helpfulness score of their first Note), so the y-axis is a proportion.

The statistical question the Regression Discontinuity Design analysis asks is if we can detect evidence that there is a jump - a discontinuity - around the threshold. Does our estimate of the likelihood of author progression change around that point?

It does - it isn’t a big effect, but the analysis suggests that the probability an author progresses to author more notes increases by around 5% if their first Note is published on the system (in absolute terms, the probability of authoring future Notes changes from ~48% to ~53%).

The strength of this analysis is that it supports a causal interpretation. It is not just that authors whose Notes are rated ‘helpful’ who go on the author more Notes - remember, we’re assuming authors whose first Notes are just above and just below the threshold for publication are effectively identical. To the extent we believe the assumptions of the analysis this is an effect of getting published. Having your first Note shown makes you more likely to author future Notes. And not getting published, which is the fate of most Notes, makes a Note author more likely to give up and drop out of the Community Notes system.

Community Notes is a neat system, thoughtfully designed. The algorithm is a clever way of harnessing partisan dynamics in the service of consensus seeking. However, no amount of algorithmic sophistication can deliver collective intelligence without a solid base of participation, and our analysis suggests that base is vulnerable. X, and other platforms which are using or thinking of adopting this approach should take note of that. There’s no Community Notes system without a community behind it.

Links: Indicator : Community fact-checking on X survived Elon Musk. It may not survive AI.

Paper: Threats to the sustainability of Community Notes on X

Previously, on Community Notes:

I’m writing more for Reasonable People while on my career break. Upgrading to a paid subscription will encourage this

Keep reading for more on what I’ve been reading on persuasion, polarisation and AI fact-checking.

Mike Caulfield: AI can walk through all the doors at once

Well put explanation of how (and why) AI is useful as a fact-checking tool

Link: AI can walk through all the doors at once

Jennifer Reich: What 20 Years of Listening to Vaccine-Hesitant Parents Has Taught Me

Reich argues that true “anti-vaxxers” are rare. Instead, lack of clarity over vaccine safety and benefits is landing with an audience which has been encouraged to focus on behavioural choices and self-responsibility for health, while discouraged from thinking about collective outcomes:

The growth of vaccine hesitance in America may feel inexplicable, ignorant or irrational to those who feel confident in their decisions to vaccinate. Yet my research suggests that this approach to vaccines is entirely logical in a culture that insists that health is the result of hard work and informed consumer decisions and too often sees illness as a personal failure.

thus

the growing unease with vaccines reflects how many parents now feel they must trust their own judgment rather than expert advice that feels generic, impersonal or politicized

Link: What 20 Years of Listening to Vaccine-Hesitant Parents Has Taught Me (Jennifer Reich, New York Times, 30 Sept 2025)

RADIO: AntiSocial

Blurbed:

“Peace talks for the culture wars. In an era of polarisation, propaganda and pile-ons, Adam Fleming helps you work out what the arguments are really about.”.

The latest episode is about the accusation that “angry middle-aged white men” are responsible for creating political division. As well as bringing to bear some interesting polling evidence on polarisation in the UK, the episode is also interesting in how the accusation bottoms out - at least in the telling of Jim Dale, the advocate for the case in this programme. Eventually he’s brought to admit that he believes ordinary people are being tricked and led astray by the silver-tongued demagoguery of the far-right.

The counter-point, made by Paul Embery, is harder to hear, but has more faith in human nature.

Link: BBC Radio 4 AntiSocial

Andrew Brown: Academic slaughter

A tale of ‘savage treachery in the rain forest and in academia’ ... gripping

Start here, with part 1

…And finally

Oatmeal comic about AI art. Too long to put here. Click

Link: https://theoatmeal.com/comics/ai_art

END

Comments? Feedback? Notes? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

I liked your MindHacks post about Chromostereopsis, a incredibly spooky phenomenon. I find some of the effect lingers with just one eye open. I also see the blue colour closer. A rarely discussed phenomenon I had only stumbled on once a bit like Aphantasia that I suffer from.

As to community, how easy is it to shift reality with paid bots. You suggest notes are not promoted until they have some minimum amount of engagement but what is making sure that engagement is not programmed?

Would the post below published on X wind up promoted or censored and would it be dictated by factual content, censorship or peoples prejudice.

https://www.arkmedic.info/p/the-pfizer-job