Dogwhistles, and the witting and unwitting polyphony of words

Reasonable People #13: When should I accuse someone of not meaning what they say? Concept slippage around "unconscious bias"; why the right isn't anti-scientific; reasoned discourse as a taught skill

There’s a story Jon Ronson tells of trying to work out exactly what David Icke believes. In Them: Adventures With Extremists (2002), Ronson tells the story of Icke’s tour of Canada. I haven’t read the book in years, so this is from memory, but two details stuck with me.

The first is how Icke sold 500 tickets at a book signing, when the week before, in the same venue, Chomsky only sold 50. There is a massive market for conspiracy theory.

The second is how the Anti Defamation League planed to disrupt Icke’s talks. He’s antisemitic, they claimed. When he talks about the world being secretly run by alien lizards, what he really means is that the world is being secretly run by Jews. The ADL is convinced Icke is talking in code, recruiting the tired conspiracy theories which have buttressed antisemitism for centuries. Ronson goes to interview Icke and comes back to the the ADL, and says something like: “You know, I don’t think when he says ‘lizards’ he means ‘Jews’. I think when he says ‘lizards’ he really means lizards”.

Dogwhistles interest me because they subvert the plane on which argument happens. If what I mean isn’t what I say, then we might be arguing about different things. How do you argue back against something which isn’t explicitly stated? When is it fair to accuse someone of meaning something different from what they say?

In her 2018 paper, Jenny Saul brings some conceptual tidying up to the term. She borrows a definition from Kimberley Witten: A dogwhistle is

a speech act designed, with intent, to allow two plausible interpretations, with one interpretation being a private, coded message targeted for a subset of the general audience, and concealed in such a way that this general audience is unaware of the existence of the second, coded interpretation

Saul then uses this to spring off and distinguish three kinds of dogwhistle:

The “explicit intentional” dogwhistle, which is where I know and the target audience know what I mean. One of her examples is the phrase “wonder working power” which George W. Bush used to signal Christian values to fundamentalist voters. I learnt another example from R, a black British man living in San Francisco. Back in 2005 or so, I, a naïve white British man, was visiting and commented on how mad it was that the American right complained about “Socialist policies” when the US had nothing that looked anything like socialism nor any prospect of it. R. explained that use of the term originated with debates about segregation from the 1950s and socialism was associated with an anti-segregationist position. So politicians on the right could complain of “socialist policies” and their white audience could hear “policies which support Black people or increase your likelihood of having to deal with them”.

Oh!

Used like this, dogwhistles are similar to insinuation. Your target knows what you mean, but you get deniability because you didn’t say it explicitly.

The “implicit intentional” dogwhistle:, which is where I know but the target audience doesn’t consciously know. These are important in political speech, says Saul, because norms of what is permissible to believe can cause a target audience to reject explicit dogwhistles, while still being vulnerable to messages which invoke those values. So, the Norm of Racial Equality, says Saul, means that messages recognised as racist, even dogwhistles, may be rejected by a politician’s audience, but many in that audience will respond to a message which invokes race indirectly. One of her examples is “inner city crime”, which connotes Black, or the use of a picture of Black man in a political advert about crime. White voters, the claim is, respond based on hidden feelings of racial resentment, but without knowing that they are doing this. The implicit intentional dogwhistle allows the politician to knowingly have their racist cake, and have it eaten.

I’m usually skeptical of the idea of implicit or unconscious meanings, but it is clear that words comes with a cloud of associations and not all of those associations will be reflected upon, even though they hover in the periphery. Choosing a dogwhistle which targets a particular audience, while having an effect but also remaining below the radar of awareness seems like an incredibly difficult thing for a politician to do deliberately. More plausible to me is that intentional dogwhistles are fully recognised by some in the target audience, and this recognition “fades out”, along with its effectiveness, as the audience becomes less keyed in to the associations of the phrase.

The “unintentional” dogwhistle, which is where neither I nor the audience know the coded message, but - as per the definition of dogwhistle - it still has an effect on the targeted audience. This can happen when an intentional dogwhistle gets taken up “in the wild” and deployed by a politician who is unaware of the original covert meaning. By using a dogwhistle term they become a vehicle of the secondary, covert, insinuation. Saul gives the example of the word “welfare” in US political speech, which, she says, now comes with a racialised associations regardless of which kind of politician uses it.

There’s a parallel here with disinformation and misinformation. Disinformation is deliberately seeded propaganda, misinformation is just non-truths sincerely passed on (I take this distinction from First Draft’s Claire Wardle, who made it, iirc, on this Govt vs Robots podcast). So disinformation becomes misinformation as the particular content moves into the wild and becomes “organically shared” non-truths, and it is hard for the rest of us - looking on at something like the anti-vaxx communities or whatever - to work out which speech acts deliberately sabotage constructive dialogue, and which are just incidentally destructive because people genuinely have strong views, bad habits, and real dialogue is simply just very very hard.

Saul’s paper then discusses the difficulties with challenging dogwhistles of all types:

it will indeed be conversationally challenging to make what has been covert explicit. People will reject what challengers say, and deny that it is true. Sanity may be, and often is, called into question. Challengers will be accused of having a political agenda. The conversation will be derailed, and it will not flow smoothly. It is difficult… and as a result it is hard to make oneself do it, or to persist in the face of this resistance. There are, then, important lessons here for those seeking to fight pernicious covert perlocutionary acts. But if challengers are aware of how these speech acts work, then it becomes clear that despite this resistance it is well worth doing.

This presents us - you, and me, reader - as insiders to the dogwhistle. In particular we are not using them, or targeted by them, but calling them out. This, as Saul suggests, is important and necessary work, despite the potential for sanity questioning and conversation derailing.

It is a flattering position, but it isn’t the only one. Saul’s taxonomy makes clear that we can be unwitting targets, or unwitting users, of dogwhistles. Given the pholyphonic potential of all words, and the precarity of the common ground that necessarily comes from wider conversations, all speech acts have the potential to contain dogwhistles - intentional and unintentional, implicit and explicit.

This is, of course, what makes textual analysis so much fun, but it creates the opportunity for much unnecessary derailment, and ambiguity over where the line is between speech which needs to be called out for the use of dogwhistles, deconstructed and replaced, and speech which contains words which have some associations for some people which some other people reject but arguing about it now will stop us getting anything done.

If this sounds abstract, I can only recommend you spend more time on internet fora and following spats on social media.

(don’t actually spend more time doing this)

The distinction between unintentional and intentional dogwhistles helps with the David Icke case. Does it matter whether he meant Jews, or lizards? If his audience hears ‘Jews’ and receives his message as consonant with an existing antisemitic understanding which has been prefigured by conspiracy theories with similar structure, maybe it doesn’t - at least not if you are speaking with them.

But how to argue with Icke himself? He wants to talk about lizards, and trying to tell him he means something else means you are immediately making an argument which is outside his confessed frame of reference.

Countering dogwhistles is easier when we are clear that the perpetrators know what they are doing, and are doing it deliberately . When we are all at risk of being unwitting perpetrators, the strategy of detecting and eliminating dogwhistles becomes a lot harder.

Saul, J. (2018). Dogwhistles, political manipulation, and philosophy of Language. New work on speech acts, 360, 84.

Ronson, J. (2002). Them: Adventures With Extremists.

BOOK REVIEW: Calvin Lai reviews “Sway: Unravelling Unconscious Bias” by Pragya Agarwal

Calvin Lai is a researcher on implicit biases, and has done great work on the effectiveness of different interventions (tl;dr - low and temporary for the most part. That’s also what we found btw). So he knows whereof he speaks when he reviews Agarwal’s book on unconscious bias. Choice quotes:

Research tells us that prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination are pervasive. Less attention is paid to how to connect these findings together. What common psychological principles underlie the prevalence of unconsciously biased discrimination?

I suspect that Agarwal's lack of emphasis on common principles is due to concept creep: an expansion of the idea of unconscious bias that goes beyond its original meaning (1). She assumes that many social disparities are necessarily caused by unconscious biases. However, many of the disparities she describes are better explained by structural causes or conscious prejudices. She writes, for example, that “implicit aversive attitudes” are an explanation for racial housing segregation. Racial housing segregation can often be more parsimoniously explained by institutional forces, such as a history of redlining, exclusionary zoning regulations, and economic inequalities. When psychological biases are considered, there is clearer evidence of real estate agents consciously steering homebuyers to certain neighborhoods on the basis of the homebuyers' race rather than as a result of unconscious bias.

Another form of concept creep is in the use of the term “unconscious” to encompass biases that are subtle but conscious. Some may just be hidden (for example, an avowed racist who lies about the reasons for treating a racial minority poorly), or they may be fast to arise (for example, a visceral reaction to a person who speaks with a foreign accent).

Related: Kenan Malik on unconscious bias training Enough of the psychobabble. Racism is not something to fix with therapy

The Coronavirus and the Right’s Scientific Counterrevolution

I love this Ari Schulman essay, which puts an essential frame on the destablisation of scientific authority in the age of covid. The key point is that it is to mischaractertise right-wing demagogues as “anti-science”, rather they are merely anti-institutional. Rather than rejecting facts, they are rejecting the established curation of facts. They still wish to borrow the aura of credibility of science, and they do this by adopting an attitude of brave truth-tellers in a world of stifling orthodoxy:

the Trump era has given all but free rein to the right’s adoption of the Galilean stance. Perhaps this was inevitable: It is the clearest model available in our culture’s scientific mythology, however tenuous a relationship it may bear to history, of a figure dissenting from mainstream scientific views, one who sees himself as persecuted by a corrupt orthodoxy to which he is the rightful heir. The Galileo myth is also continuous with a long history of scientific gadflies who see themselves carrying forward the legacy of the Enlightenment model of skeptical inquiry: the radical individual freed from the oppression of institutions, in something of a funhouse-mirror image of the real work of science. The problem we’re now seeing, however, is that the Galileo model now often eventuates not only in counterinstitutional inquiry, but also in bad science

So the the cultural veneration of science means that even debunking of science borrows a scientific model.

The perceived need for debunking is driven by an establishment attitude to the public, as object and obstacle to scientific informed policy. Around coronavirus, Schulman argues, the public was treated as an audience to be informed (or misinformed, in the case of the lack of need for masks), to be persuaded, rather than as competent adults capable of participating.

The Galilean right senses, not without reason, that invocations of science often function as a mask for social, rhetorical, and political power. The trouble is that instead of forging a more humane relationship with science, gadflies on the right have decided to steal that power for themselves. Entranced by a story about how they have triumphed over the slavishness of groupthink, the Galileans have only become more manipulable, more credulous, more deluded.

Read the whole thing for the full diagnosis of the maladies of our relationship with science, and expertise, on both the left and the right.

Reasoned Discourse as a Vital 21st-Century Skill - Deanna Kuhn (2016)

Epistemological understanding—the understanding of how we know what we claim to – develops in a predictable sequence. Through at least their first decade, children believe that we know the world directly and first hand—just look and see and truth reveals itself as a set of known facts. By their second decade, the discovery that the beliefs even of alleged experts differ typically leads to a radical turnabout. A world of certain facts is replaced by one of knowledge as freely chosen opinions—how things seem to me. Knowledge, once entirely objective, is now treated as entirely subjective – believe whatever you want.

Only some individuals progress to a third epistemological stance in which objective and subjective dimensions of knowing are coordinated and knowledge consists of judgments, made within a framework of alternatives and evidence and expressing our best current understanding, though subject always to change.

She also identifies these two essential “intellectual skills” for good argumentation:

the distinction between explanations which are possible, plausible and compelling

recognising that most complex things don’t have simple, unitary, causes

Paper: Design Thinking in Argumentation Theory and Practice

This essay proposes a design perspective on argumentation, intended as complementary to empirical and critical scholarship. In any substantive domain, design can provide insights that differ from those provided by scientific or humanistic perspectives. For argumentation, the key advantage of a design perspective is the recognition that humanity’s natural capacity for reason and reasonableness can be extended through inventions that improve on unaided human intellect. Historically, these inventions have fallen into three broad classes: logical systems, scientific methods, and disputation frameworks. Behind each such invention is a specifiable “design hypothesis”: an idea about how to decrease error or how to increase the quality of outcomes from reasoning

Jackson, S. (2015). Design thinking in argumentation theory and practice. Argumentation, 29(3), 243-263.

New project funded! Understanding online political advertising: perceptions, uses and regulation

We’ll be hiring for a January 2021 start

Also, Andreas has two 5 year post-docs doing NLP on his 5-year ERC project Automated Verification of Textual Claims (AVeriTeC).

And finally…

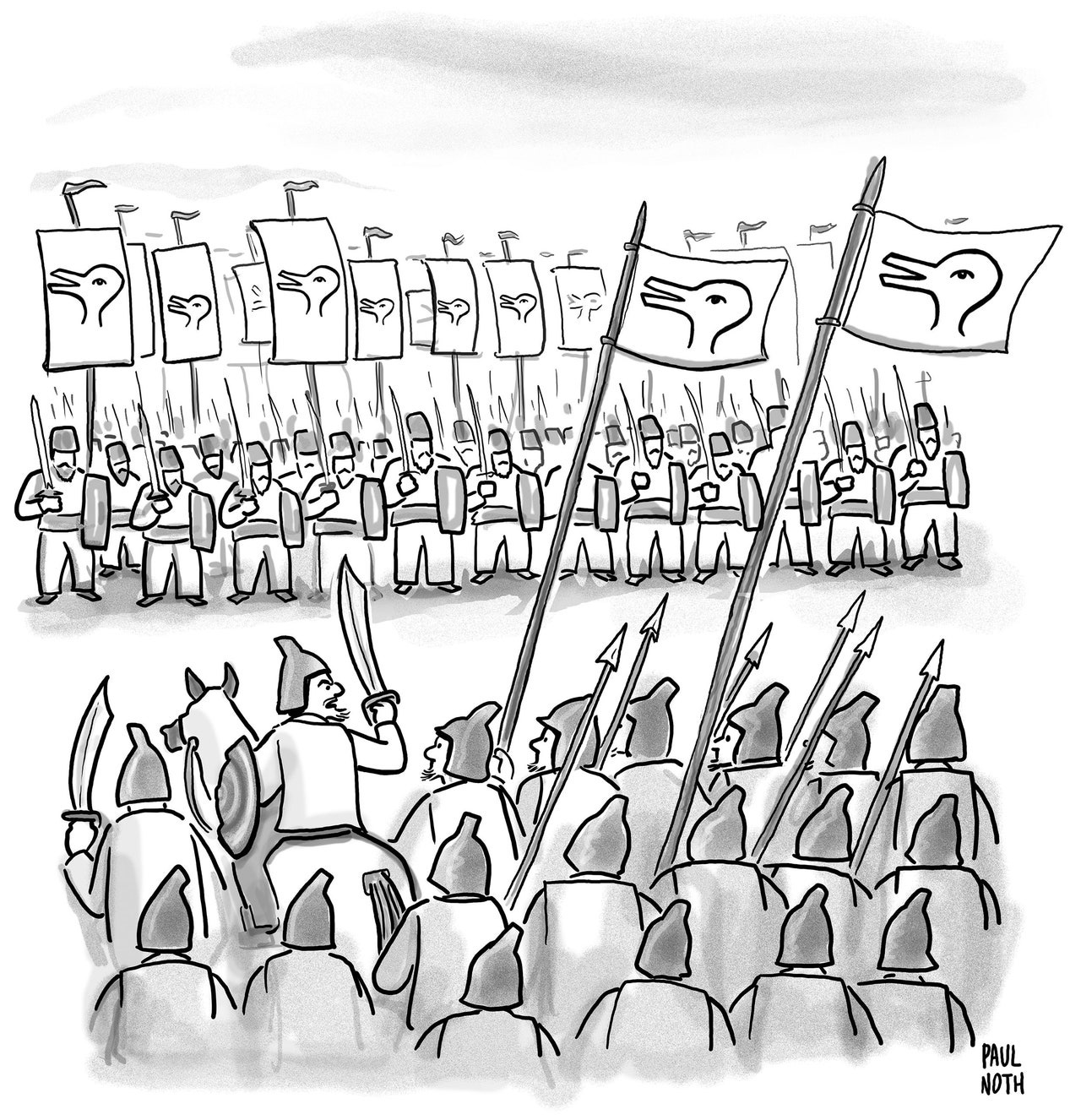

“There can be no peace until they renounce their Rabbit God and accept our Duck God.”

New Yorker cartoon by Paul Noth

END