Pathologies of collective life

Reasonable People #54 : Two phenomena which derail useful meetings, and thoughts on how to tame them.

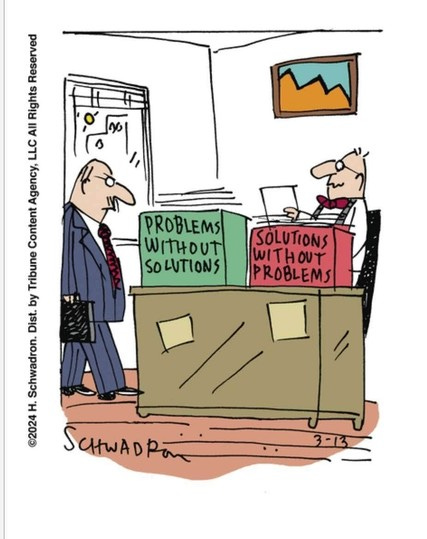

Particular welcome to everyone who subscribed in the last four months and forgot they had because I haven’t posted. I make no promises on frequency or relevance of posts, only that I will supply some mix of speculation, commentary and reporting around the psychology of reason, persuasion and argumentation. Scroll to the end for short reports and a cartoon, keep reading for today’s main thought…

Like all institutional people, I go to a lot of meetings. Their quirks interest me.

You share 50% a sizeable proportion of your DNA with a banana. That's not because you have genes for being yellow and delicious, but because you share management genes, genes responsible for turning on and off other genes. Genetic bureaucracy.

If evolution couldn't cut bureaucracy out down to less than 50% of the system, I don't have much hope for human organisations. [1]

But still, there are a lot of meetings. Their quirks interest me.

Recently, as part of a large project I'm part of, the issue of a logo for the project came up. An important issue. Not as important as deciding on the project priorities, or on how we allocate the budget, or who will work on what. So maybe, in the scheme of things, not that important. I recognised the Logo Decision immediately as a member of the class of Bike Shed Issues and so could turn to checking my email, confident in the knowledge that the rest of our meeting would be dominated by discussion of the logo which didn't require my attention and would proceed just as well - or badly - without me as with it.

Bike Shed Issues are from C Northcote Parkinson, the same Parkinson of Parkinson's Law ("Use expands to fill capacity"). In his book, Parkinson's Law: The Pursuit of Progress (1958), Parkinson chronicles a whole set of observations with a general applicability, the sort of things that will be familiar to anyone who enjoys membership of an organisation, large or small.

One principle from the book is that meetings will be dominated by discussion of the least important issue, while the most important issue will receive least attention. Parkinson even provides the generating mechanism behind this, which I'm going come back to and rephrase in the terms of the psychology of reason.

Imagine a planning meeting for a new nuclear reactor. First item: design specifications for the reactor. Hard choices, trading off safety, efficiency, cost. What parameters for the cooling system? Which mixture of isotopes? How many failsafes on the warning systems? Not many in the meeting can be experts in all these issues, and even if you have an opinion you may show yourself up for a fool if you speak out. Arguably the most important topic in the meeting is finished off in five minutes, the engineers recommendations are either waived through or sent back for some final checks. Next up: what colour to paint the bike sheds in the reactor parking lot. An issue of no consequence to the running of the reactor, and hence one which everyone can fearlessly have an opinion on. As a bonus, the issue of colour is one we all expertise in - or at least feel we have a grasp of what is necessary to take part in discussion of the issue. I like pink because it is friendly. You like green because bikes are a sustainable transport solution. Maggie suggests having a mural painted to deter graffiti. It's a game everyone can play, and we'll have a great time. Discussion of the bike sheds takes up the remaining 55 minutes of the meeting.

That more time is spent on less important issues is the effect. The cause is the ability of people to chip in, which is inversely proportional to the difficult of the choices and the exclusiveness of the background required.

In my own case, the chair managed to restrict discussion of the project logo to ten minutes, but even his legendarily ruthless timekeeping couldn't prevent several follow up points over email and the circulation of the iterated proposal and poll for voting on the new options.

A related phenonenon was introduced to me by Stephen Curry, called “admiring the problem”. This is where sophisticated discussions of complex issues devolve into inaction by the sheer weight of the cleverness participants in the discussion bring to it. The phase captures the feeling I've often had that I'm in a room full of exceptionally clever and well informed people but we are competing to provide reasons why everything is impossible, rather than direct our collective efforts towards establishing what is possible.

Now I've come to think of "admiring the problem" as the same kind of phenomenon as Bike Shedding, and if we recognised the forces driving it, we could maybe make the most of it, or at least reconcile ourselves to why it needs to happen.

Discussion is more than just exchanging information, more than providing reasons even. All discussions build on a set of shared understandings, a common ground [2]. The better you know each other, the more common ground. "There's a buffet car on this train" says my wife, and I know she is asking me to get her an americano with milk - because of our common ground which includes that this is what she likes to drink at around this time in the morning, and I am the one with Euros in my pocket. When you know each other well you can say less and mean more, because you're building on a common ground of shared knowledge which has already been established.

Through the lens of common ground, the quirks of meetings make more sense. We're colleagues, not intimates. It may be that we all know the obvious, but that is not enough - the common ground for discussion needs to be established. The obvious needs to be stated - who is who, why we're here, what the items on the agenda are. Not because anybody doesn't know these things, but because we need to know that everybody else knows that everybody else knows these things. Knowing what everyone else knows is the common ground. Only with this in place we can proceed to discuss the business of the day. The Bike Shed discussion proceeds with such alacrity because the common ground is manifest - everyone knows everyone knows about colour choices. The reactor specifications discussion is so hard because even the experts in the room can't be sure what elements of their expertise are shared with the other experts.

Meetings begin with introductions so we all know who each other are. Maybe they should all also begin with an introduction to the problem, so we know what each other know. The Amazon formula - the meeting begin with everyone reading a two page briefing [3] - has the same effect, forcing a common ground on everyone - not only does everyone know what is in the briefing, but they know that everyone else knows. They’ve just seen them reading it at the same time as them.

Next time I chair a meeting, I might formally declare an initial portion of the meeting for admiring the problem. With the difficulty of the problem aired for all to acknowledge, maybe we could then more successfully more the discussion onward to practical actions.

Institutional life is about more than decisions, or exchange of information. We feel sympathy or solidarity with our fellows, understand each other based on what we can share about how we see the world. I used to be a lot more impatient with the amount of time spent on the obvious in meetings. Now I see the obvious as a necessary part of collective intelligence. It needs to be stated and restated so a group can constitute and collectively know what it knows. Effective discussions begin with the obvious. The only problem is if they end there too. Common ground is comfortable, and some experiment results suggest that groups can underperform at problem solving because people focus on shared knowledge, rather than each individual contributing the unique information they posses to the common pool [4]. Now I recognise the power of common knowledge I might relax more when we start with it, but also invent strategies to contain the time we spend on it, so we can more forward.

That's my ambition, at least. But right now you'll have to excuse me, I need to vote in that poll on the project logo.

Footnotes …

[1] I owe this observation to Andrew Brown, who observed it or reported it from one of the interviewees for his great book on intellectual history of mid century evolutionary biology The Darwin Wars. At least I think I owe the observation to him - I’m writing on a train so my fact checking abilities are limited. EDIT: Thanks to Ruben C. Arslan for the fact-check on this (see comments)

[2] Common Knowledge “Reasonable People #31: Why the Heard/Depp case dominated the front pages, why a crypto firm paid $14 million to advertise during the Super Bowl, and why video calls are likely to stay annoying”

[3] A convention borrowed from Edward Tufte. I think he reports this here https://pca.st/episode/d9f64c01-eb97-485e-b0b8-309460d845e6

[4] Wittenbaum, G. M., & Park, E. S. (2001). The Collective Preference for Shared Information. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00118

Recent and related from Reasonable People

(March 2024) AI-juiced political microtargeting : Reasonable People #53 looking carefully at the claims in one study which uses generative AI to customise ads to personality type

(March 2024) Propaganda is dangerous, but not because it is persuasive : Reasonable People #52: I pick at the claim that propaganda "doesn't work".

(June 2022) Common knowledge : Reasonable People #31: Why the Heard/Depp case dominated the front pages, why a crypto firm paid $14 million to advertise during the Super Bowl, and why video calls are likely to stay annoying

(March 2020) Arguing across common ground : Reasonable People #3: When good reasons are a bad guide

PAPER: Collaboratively adding context to social media posts reduces the sharing of false news

Abstract

We build a novel database of around 285,000 notes from the Twitter Community Notes program to analyze the causal influence of appending contextual information to potentially misleading posts on their dissemination. Employing a difference in difference design, our findings reveal that adding context below a tweet reduces the number of retweets by almost half. A significant, albeit smaller, effect is observed when focusing on the number of replies or quotes. Community Notes also increase by 80% the probability that a tweet is deleted by its creator. The post-treatment impact is substantial, but the overall effect on tweet virality is contingent upon the timing of the contextual information's publication. Our research concludes that, although crowdsourced fact-checking is effective, its current speed may not be adequate to substantially reduce the dissemination of misleading information on social media.

Renault, T., Amariles, D. R., & Troussel, A. (2024). Collaboratively adding context to social media posts reduces the sharing of false news. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.02803.

Thread from lead author: https://twitter.com/captaineco_fr/status/1775890025705841097

I think Community Notes are a really interesting innovation in social media and the collective negotiation of our shared information environments. They are criticised for often coming too slow (since errors often spread very quickly), and for being a get-out for x/twitter having to spend real money on a moderation team. These can be true and there still be good aspects of the experiment we should learn from.

PAPER: Alice in Wonderland: Simple Tasks Showing Complete Reasoning Breakdown in State-Of-the-Art Large Language Models

Abstract:

Large Language Models (LLMs) are often described as being instances of foundation models - that is, models that transfer strongly across various tasks and conditions in few-show or zero-shot manner, while exhibiting scaling laws that predict function improvement when increasing the pre-training scale. These claims of excelling in different functions and tasks rely on measurements taken across various sets of standardized benchmarks showing high scores for such models. We demonstrate here a dramatic breakdown of function and reasoning capabilities of state-of-the-art models trained at the largest available scales which claim strong function, using a simple, short, conventional common sense problem formulated in concise natural language, easily solvable by humans. The breakdown is dramatic, as models also express strong overconfidence in their wrong solutions, while providing often non-sensical "reasoning"-like explanations akin to confabulations to justify and backup the validity of their clearly failed responses, making them sound plausible. Various standard interventions in an attempt to get the right solution, like various type of enhanced prompting, or urging the models to reconsider the wrong solutions again by multi step re-evaluation, fail. We take these initial observations to the scientific and technological community to stimulate urgent re-assessment of the claimed capabilities of current generation of LLMs, Such re-assessment also requires common action to create standardized benchmarks that would allow proper detection of such basic reasoning deficits that obviously manage to remain undiscovered by current state-of-the-art evaluation procedures and benchmarks. Code for reproducing experiments in the paper and raw experiments data can be found at this https URL

Nezhurina, M., Cipolina-Kun, L., Cherti, M., & Jitsev, J. (2024). Alice in Wonderland: Simple Tasks Showing Complete Reasoning Breakdown in State-Of-the-Art Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.02061.

This is their “simple, short, conventional common sense problem formulated in concise natural language, easily solvable by humans” (and the answer):

"Alice has N brothers and she also has M sisters. How many sisters does

Alice’s brother have?".

In this instance, the correct answer would be M + 1

And finally

As Kai Arzheimer observed, one for social scientists:

END

Comments? Feedback? Restatements of the obvious? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

Way back when, I similarly mused about *accountable shared ground* as the thing that big org meetings produce and that make them unavoidably boring. https://speakerdeck.com/codingconduct/un-boring-meetings

Actually working at Amazon and participating in those briefing-before-talking kinds of meetings, I really like it as a practice and recommend!

Re bananas: that statement doesn’t have much meaning but even interpreted charitably it doesn’t seem to be true https://lab.dessimoz.org/blog/2020/12/08/human-banana-orthologs