The Epistemic IKEA effect

Reasonable People #20: The benefits of letting people come to their own conclusions

On my desk is a pen holder. It's a series of triangular prisms, each 4 inches deep, stacked together. Each prism is made from one third of the lid of an old pizza box, held together with packing tape, which is peeling.

Nobody would pick this item out of a skip, but I am inordinately fond of it. The reason of course is because it is my pen holder. I made it, measuring out and cutting each 4" x 12" piece of pizza box; taping each unit; taping units together to make the bigger pyramid.

There's a paper on this phenomenon, the "IKEA effect", named after the furniture store famous for selling flatpack furniture which you assemble yourself.

From Norton, Mochon & Ariely’s (2012) abstract:

In four studies in which consumers assembled IKEA boxes, folded origami, and built sets of Legos, we demonstrate and investigate boundary conditions for the IKEA effect — the increase in valuation of self-made products. Participants saw their amateurish creations as similar in value to experts' creations, and expected others to share their opinions. We show that labor leads to love only when labor results in successful completion of tasks; when participants built and then destroyed their creations, or failed to complete them, the IKEA effect dissipated. Finally, we show that labor increases valuation for both “do-it-yourselfers” and novices.

Norton and colleagues discuss the psychological drivers of the IKEA effect. Perhaps it is because of the effort itself, or the chance to be competent at something? Perhaps the signalling value of those things (“Look what I made!”)? Or the positive feelings associated with being a “smart shopper”, not needing someone to pre-build something for you?

Something they don’t consider, but which seems a plausible factor to me, is assurance: if you make something yourself you have insight into how reliably it is constructed. Not necessarily that it is perfect, but how the parts fit together, and sense of what might go wrong and how it could be fixed if it does.

This assurance can be false, of course. If the world gave you shoddy materials, or a bad assembly instructions, your care and attention may produce an unreliable construction, one which you are inordinately attached to but which should not be trusted.

* * *

Much has been written about the negative effects of our current social media landscape on belief formation. Here’s Zeynep Tufekci on how the YouTube algorithm drives you towards more extreme versions of whatever content you start with. Here’s danah boyd on how bad actors exploit ‘data voids’ in the information ecosystem.

It’s right to focus on structures and bad actors, but since I’m a psychologist I also like to think about the individuals who actively pursue misinformation. Many results show how hard it can be to shift people’s beliefs, even when there’s good evidence they’re mistaken. Perhaps a factor here is a kind of IKEA effect for beliefs; we become inordinately attached views we’ve built ourselves, even when those views are assembled out of parts which are unreliable.

All the factors which could drive a physical IKEA effect could also play a role in an epistemic IKEA effect : we value the effort we put in to gathering information, enjoy the feelings of mastery that results from insight. We’re proud to show off what we’ve learnt, and to show that we’re savvy epistemic actors, who can figure things out for themselves.

I was peripherally involved with a Shift/Wellcome Trust project which did a “digital ethnography” of vaccine hesitant parents - sitting with these people as they used the internet, seeing how they came across vaccine/health information and how they reacted to it and shared it. (I talk about this more in my talk at Truth and Trust Online 2019). One thing which stood out for me was how common it was for people who believed vaccines myths to say “I’ve done the research”.

Views of vaccine hesitant parents on Facebook. “Please do careful research on this”, “I researched this”, “I’ve done AT LEAST one hour of research a day for nine months”.

This supports the idea that the effort of coming to your own conclusions plays a role in people’s attachment to mistaken beliefs. Perhaps it also supports the idea that it is easy to overestimate your own skill in assembling a view, and underestimate how badly you’ve been mislead by the quality of the material you’ve been viewing. (And of course this isn’t just a risk for people who don’t know what “real research” is. With covid we’ve seen how many scholars are not immune to being mislead when they stumble out of their area of expertise).

* * *

There may be a way to leverage this epistemic IKEA effect for good, as demonstrated in new work by Sacha Altay, Anne-Sophie Hacquin, Coralie Chevallier & Hugo Mercier in a preprint “Information Delivered by a Chatbot Has a Positive Impact on COVID-19 Vaccines Attitudes and Intentions”.

Important context for this is that previous studies which attempt to shift vaccine attitudes have been unsuccessful or had only modest effects (e.g. Nyhan et al, 2014).

Altay and colleagues reasoned that one block to persuasion around vaccine information was the need to deal with counter-arguments, which naturally arise when you present people with information that contradicts prior beliefs (this, they argue, is why small group discussions are such a great format for changing minds).

The research team used a survey of a representative sample of the French population, one of the most vaccine hesitant in the world, to gather common questions about the covid-19 vaccines. They then organised quality information and arguments addressing these questions in a way that could be explored through an online chatbot. The chatbot allows you to select from pre-set responses (rather than respond to free text) and so explore vaccine information (which participants in the experiment did, for half of them for more than 5 minutes, compared to a control condition which just received a much abridged summary of the vaccine information).

The effects were substantial:

a 37% increase in participants holding positive [vaccine] attitudes, and a 20% decrease in participants saying they would not get vaccinated. Moreover, instead of observing, as in past experiments, backfire effects, the participants who held the most negative views changed their opinions the most.

You can interact with their chatbot (and practice your French) here http://51.210.106.163/chatbot/

* * *

When we want to persuade people it is tempting to bludgeon them with what we perceive are the facts, to push on them - wholesale - our particular and alternative view of the world. Instead, it might be productive to think about how we can let people ‘roll their own’ views, and take advantage of the instinct we all have to put things together ourselves, to be proud of the conclusions we come to.

* * *

References:

Altay, S., Hacquin, A., Chevallier, C., & Mercier, H. (2021, January 4). Information Delivered by a Chatbot Has a Positive Impact on COVID-19 Vaccines Attitudes and Intentions. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/eb2gt (tweet thread)

danah boyd. Media Manipulation, Strategic Amplification, and Responsible Journalism. Sep 14, 2018.

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. Journal of consumer psychology, 22(3), 453-460. (PDF)

Tom Stafford. Rational Choices About Who To Trust, at Truth and Trust Online 2019. 5 Oct 2019 (video, transcript)

Zeynep Tufekci, YouTube, the Great Radicalizer. New York Times, March 10, 2018

Paper: Why Facts Are Not Enough: Understanding and Managing the Motivated Rejection of Science

By Matthew Hornsey

Abstract:

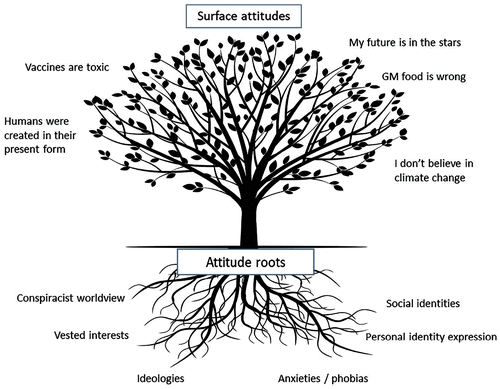

Efforts to change the attitudes of creationists, antivaccination advocates, and climate skeptics by simply providing evidence have had limited success. Motivated reasoning helps make sense of this communication challenge: If people are motivated to hold a scientifically unorthodox belief, they selectively interpret evidence to reinforce their preferred position. In the current article, I summarize research on six psychological roots from which science-skeptical attitudes grow: (a) ideologies, (b) vested interests, (c) conspiracist worldviews, (d) fears and phobias, (e) personal-identity expression, and (f) social-identity needs. The case is made that effective science communication relies on understanding and attending to these underlying motivations.

My worry about this account is that it risks trying to explain the rejection of science without explaining the acceptance of science. That you reject science because you are a conspiracy theorist, while I accept science because it is correct, is asymmetrical - your rejection and my acceptance are fundamentally different.

I like the call to focus on the roots of attitudes, rather than their surface expression. Here’s a diagram from the paper:

Hornsey, M. J. (2020). Why Facts Are Not Enough: Understanding and Managing the Motivated Rejection of Science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420969364

Post: The Dunning-Kruger effect probably is real

The Dunning-Kruger effect is where you are “unskilled and unaware of it”, or specifically that the people with least competance in any domain are most likely to overestimate their ability. Graph from the original paper:

Recently there has been some criticisms that the original findings which support the effect are the result of a statistical artifact, rather than strong evidence that lack of ability is likely to go hand-in-hand with believing you are above average. Ben Vincent picks up the challenge, with a really neat post which uses simulation to reproduce the original challenge results and pick them apart. He concludes that the Dunning-Kruger effect probably is real, and along the way showcases the value of using computational modelling to aid our thinking about psychological results.

Ben Vincent. The Dunning-Kruger effect probably is real. 29 Dec 2020.

Ben on twitter @inferencelab, web: inferencelab.com

And finally…

Those good tweets / tweet threads:

Gear change, discussion of Brexit: