Thinking in Public

A meme-tastic reasonable People #8 : half-thoughts on epistemically productive online environments

Before the internet was everywhere, back when it was still a place, there was a certain ethic associated with self-publishing content. Part of that ethic was commitment. Back when blogging was a thing, people would labouriously craft posts (hundreds, even thousands of words!), linking out to external pages, or back to previous things they'd written, much in the style of academic citations. On the sidebar of these personal weblogs you would find a curated "blogroll" of websites the author would regularly read and link to.

Reader, I was there.

To give you a sense of this, in 2003 I thought to start a psychology blog, so I looked around to see if such a thing existed already. I could find literally one or two. That’s right - just small handfull of people writing regularly about psychology research and posting it for free on the internet.

It's all different now. When posts are shorter, notifications are incessant (and direct to your phone), and liking, replying and embedding other content is all slick and often merely the push of a button.

But that isn't all that has changed.

Part of the ethic of the earlier internet was a palpable commitment to thinking in public. Blogging, for lots of people, wasn't about self-publicity but was a way of working things out, out loud. It was okay to make mistakes, or publish a half thought. There was a tightly networked conversation with local networks of blogs, authored by people who wrote in response to each other, who got to know other though the back and forth of comments and response posts. The shared ethic was that by open discussion we'd collectively advance.

I was thinking about this commitment to public thought after I heard Natalie Ashton's lecture, 'Productive Online Environments: Why Twitter is (Epistemically) Better than Facebook' (Department of Philosophy seminar, University of Sheffield, 6th March 2020).

Ashton's argument encouraged us to think about how the platform-properties of online environments have epistemic effects. Specifically she argued that the types of connections they allow, the engagement style, and content and privacy settings mean twitter is more 'epistemically productive'.

This made me think about what I loved and hated about blogging culture, and what I love and hate about social media now. Both, I still believe, can be incredibly epistemically productive.

There's a lovely 2002 paper called 'The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth' in which two psychologists show that people often overestimate the depth of their understanding. The experiment uses a popular children's book ("The Way Things Work"), which is one of reasons I like it.

Taking examples from this book - "How a helicopter works" "How a door lock works", "How a flushing toilet works" - participants were first challenged to rate their understanding of how that thing, X, worked. They were then asked to generate a written explanation, then asked questions to test their understanding, then presented with an expert's answer on how X worked. This process revealed what you must have guessed by now - participants were massively overconfident about how well they understood these things. Their explanations were superficial, their answers to detailed question wrong and their response to expert understanding was an embarrassed realisation of their ignorance.

We all suffer this cognitive illusion, mistaking our familiarity for understanding. We all have experience of flushing a toilet, or using a door lock, or voting on how the country is run. That ease of interaction disguises the inner working from us; often ignorance of the inner working is necessary for a fluent interaction.

An illusion of explanatory depth can exist between us too. If I know the answer is X, and you know the answer is X, but we never discuss exactly what we mean by X, then we might rub along in mutual incomprehension, thinking we are on the same side, yelling at all the non-Xers out there without discovering our disagreements.

Writing can be an antidote for the illusion of explanatory depth, but you have to imagine a skeptical audience rather than a cheering one. When you write you are trying to capture thoughts and explain them in a way that a distant other can understand them. I don't know who you are, and I don't know what you know. I can't assume we agree, so I try and bridge the common ground I assume we do share: words, some rudimentary features of the world. Can I build an argument from just these?

The more I know we have in common the easier it is for me to communicate, but also the greater the risk I'll rely on shortcuts, falling back on things which are a familiar part of our shared language but which hide an explanatory gap.

Humour seems particular vulnerable to hiding explanatory gaps - something you can get an insight into by skimming the gags and put downs of those you disagree with.

For you, dear reader, I crossed the Atlantic and my natural political inclinations to browse pro-gun and pro-Trump memes. Let's try this now, imagine you are a European liberal:

Or

My reaction to these put downs and owns isn't to feel put down or owned. It's "That's not the point?!". They don't make any sense to me as arguments, but they have currency as arguments within a different ideological group - or perhaps as tokens of more elaborated arguments, that I would disagree with if given the chance.

Another

Mate! These are not exclusive options!

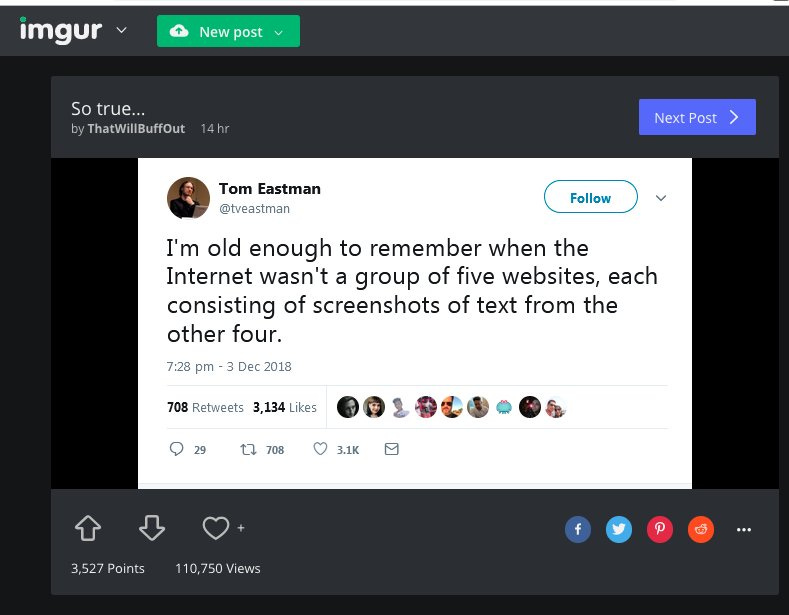

I started by saying that thinking in public could be a cure for the illusion of explanatory depth, but it obviously isn't always. How does social media work for or against this effect, and how is it different from "1st generation" blogging? Something about the extreme brevity (twitter used to be 140 characters!), the unidimensional feedback (meaning all platforms focus us on number of views or likes) and the hyper-social nature of these spaces (meaning we play to our in-crowd?), makes reasonable discussion harder. Means we get memes rather than arguments.

One reason I disagree with Ashton's conclusion that twitter is epistemically better than facebook is because facebook is more often layered on top of existing non-virtual connections. I can argue with my brother on facebook, but bring in the common ground we have from interactions outside of facebook (and the knowledge that clever puts downs have a cost because I have to face him across the Christmas dinner table).

There’s design-oriented discussion to be had about how social media platforms could be re-worked to support better collective thought. Probably you would turn off the retweet button and share buttons, remove the count of likes on each post, and make content less “discoverable” to encourage the sense of semi-private conversation -- all the exact opposite of the design changes made in the last ten years on twitter.

In the spirit of half thoughts I am going to leave this here.

If you enjoy the newsletter, please consider forwarding it, or telling people about it by sharing this link https://tomstafford.substack.com and if you can complete or complement any of my half thoughts, please hit reply and get in touch

References

Rozenblit, L., & Keil, F. (2002). The misunderstood limits of folk science: An illusion of explanatory depth. Cognitive science, 26(5), 521-562.

A 2014 article I wrote for BBC Furure about using the illusion of explanatory depth in political discussions: The best way to win an argument

Other stuff

WHO Best practice guidance: How to respond to vocal vaccine deniers in public

Great example of practical advice on how to do science communication in a hostile environment. Thanks to Kat Jennings for the recommendation

Ipsos Mori: Trust - The Truth (Sept 2019)

Over the last twenty years the number of people who believe "most people can be trusted" has increased, there is increased in trust of print media, and stable trust in government. Which is all counter-narrative to some extent. Some of the “erosion of trust” in experts is just a loss of deference. No doubt there are interesting changes (and less interesting research articles) being written about how 2020 will affect trust in authorities, political and scientific.

Foreign Policy: Confucianism Isn’t Helping Beat the Coronavirus

Cultural tropes don’t explain South Korea’s success against COVID-19. Competent leadership does.

A nice illustration of how false beliefs about (ir)rationality and bias, especially in other people or other groups, can stop you seeing what is really going on:

Ultimately, South Korea’s success is thanks to competent leadership that inspired public trust. No sacred Confucian text advised Korean health officials to summon medical companies and told them to ramp up testing capacity when Korea had only four known cases of COVID-19. No Asian wisdom made Korean doctors think they should test everyone with pneumonia symptoms regardless of travel history, which led to the discovery of the now infamous “Patient 31” and the suppression of the massive coronavirus cluster in the city of Daegu caused by the secretive Shincheonji cult. The South Korean public isn’t hoarding toilet paper not because they are sheep with no individual agency but because they plainly saw that their government was committed to being transparent and trusted it to act in their interest.

Mindhacks.com: Do we suffer ‘behavioural fatigue’ for pandemic prevention measures?

Rapid mini-review from the great @vaughanbell, which I think also illustrates something about how psychology research is packaged. Lots of epidemiological models included decay of adherence to new social practices, without committing to a thick psychological interpretation of why adherence decays. In this process of explaining this collapses into describing it as “fatigue”, which is psychologically-thick (in that it implies that the mechanism is universal, inevitable etc). This secondary, thick “explanation” then (possibly) has a feedback on which policies decision makers think are possible/desirable.

Related: thoughtful thread from Joe Morrison on his aborted philosophy journey with ‘lay epidemiology’

BBC Future: Why smart people believe coronavirus myths by David Robson

Research here will be familiar to regular RP readers (if there are there any of those yet). Here’s a clue from David:

Quick brain teaser: Emily’s father has three daughters. The first two are named April and May. What is the third daughter’s name?

If you answered “June”, you might be more likely to spread fake news about coronavirus.

Unherd: Don’t trust the psychologists on coronavirus: Many of the responses to Covid-19 come from a deeply-flawed discipline by Stuart Ritchie

Yep

…And finally

XKCD’s 2007 Map of Online Communities

(And compare 2010 map here)