Unfollow

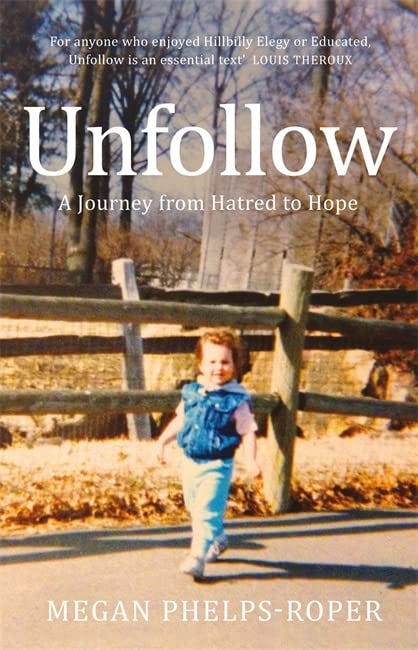

Reasonable People #28: Megan Phelps-Roper's story of losing faith in the Westboro Baptist Church

Westboro Baptist Church is a small faith-based community from Topeka, Kansas. Their white church building is surrounded by the homes of families who are part of the Church. They are a SPLC designated hate group, who you may know from their inflammatorily named website - godhatesfags.com - or from their devoted picketing of the funerals of US soldiers killed abroad.

They are still going. On May 4th 2022 they are picketing the T-Mobile Centre in Kansas City, because Justin Bieber is playing there. You can read their blog and hear about how deaths in Ukraine, or new coronavirus variants, reflect God’s Judgement on a sinful world.

Megan-Phelps Roper is the granddaughter of the founder of the church, and spent 26 years with the church. She was, as she self-describes, “all in”: picketing, proselytising, giving interviews and leading the charge of the Church’s flamboyant social media presence.

In November 2012 she left the church, her family, and the absolute certainty of their doctrine. Unfollow is her autobiography, the story of her life and the history of her coming to the realisation that her beliefs, however fervently held, were wrong.

Unfollow gives an up close view of what it was like inside a group whose beliefs are dramatically at odds with wider society. The Church’s beliefs seem so extreme, their commitment to alienating themselves from the mainstream so complete, that I found myself surprised with some of what Phelps-Roper described about Westboro Baptist Church.

I though a hate group would be dominated by hate - by cruelty, misery and paranoia. Instead, Phelps-Roper describes a childhood which had many idyllic elements. She lived with her large extended family (one of eleven siblings!) and fellow church members, with routines dominated by service (such as picketing) but also lots of fun, laughter and love. Meals and parties. The extent of her love for her family shines on every page, and you can read the whole book as a letter of explanation to family still in the church (including, as far as I know, her parents and the majority of her siblings). Unfollow also describes authoritarian, cruel and psychologically manipulative elements to her upbringing, but the extent - and sustaining joy - of the tight, loving, family bonds were not what I expected, even if they make sense (since Church members tried to provoke the rest of the world, obviously they would need to stick tight together).

I thought a hate group would be closed to outside influences, but it seems the Church welcomed them in. They were so confident in their rightness that they didn’t see any need to ban modern influences like Hollywood movies or pop music. In fact, all the better for Church members to develop their hurtful parodies of current events and popular culture. Elton John’s “Candle in the wind” was rewritten as “Harlot full of sin” by the Church so they could celebrate the death of Princess Diana . Phelps-Roper’s description of the joyful siblings singing

But it seems to me you lived your life

Like a harlot full of sin

God cut you off

Now the flames set in

typifies the Church’s genius for trolling the pain of the rest of the world, and provides an image which captures the paradox of a loving hate group.

I thought a hate group would shut down all discussion and debate, settling all matters with the Founder saying “It’s so because I say so, because God says so”. There’s some of that, especially towards the end of her time in the Church, but the atmosphere of Phelp-Roper’s childhood was one that positively embraced discussion and debate. How else could you train a child on a picket line holding a sign saying “Thank God for dead soldiers” to argue their corner? Fred Phelps, the Church founder was a lawyer, and his children worked in family business. In a weird way, the totalitarian nature of their ideology encouraged a constant, communal, litigation. It’s one way to develop consensus, and consensus was essential because a signature of Church beliefs was agreeing to disagree wasn’t possible. Everyone not completely Right was 100% Wrong, and consequently damned.

(There’s another way to achieve group consensus of course - have a single person or small group decide what the Law is and pass it down to everyone else. Phelps-Roper describes what she calls ‘a coup’ in the leadership of the Church during her last years there. A small group of men appointed themselves Elders and declared that all decisions would be made by them, and all others (women or children) follow the instruction of their fathers or husbands. This stage of the church sounds more like the description I had originally expected. Dissent stifled by isolating doubters, gaslighting, and outright bullying).

* * *

Like the saying about bankruptcy, Phelps-Roper’s loss of faith happened two ways. Slowly, then all at once. Unfollow follows various threads, which I give my re-description of here.

First, the importance of consistency (and inconsistency). Phelps-Roper diligently documents her struggles with Church doctrine. In a way, the absolutist nature of the Church’s beliefs acts to make even a single example of inconsistency stick out. This is so much so that she recalls the first doubts she had about teachings from a Church elder, doubts from years prior to her apostasy. She recognises the efforts that she made, during the years of being a believer, to push these doubts out of her mind, but eventually the seed of merely recognising inconsistency grew, and she found herself doubting more and more of the slogans that the Church picketed with, was able to apply the precepts preached by the Church to the Church’s own behaviour. The contradicts created a tension, not one that couldn’t be skimmed over, pushed out of mind or avoided, but a tension nonetheless which added the pressure when her faith did eventually break (see RP #7 for more on consistency).

A second factor was the social changes in the Church, and the way various members (including Phelp-Roper’s own mother and sister) were treated. There’s self-interest here, to realise something is wrong when it affects your loved ones, but also it is another reflection of the powerful need for consistency: what is unfairness if not inconsistency in the social domain?

Third on my list, and close to my heart, is social media. Phelps-Roper (@meganphelps) describes her preoccupation with twitter, roughly in the period 2009-2012 (coincidentally the golden age of that platform in my opinion). You can search back through her timeline and find the tweets from those days. Here’s a fairly innocuous one (#GodHatesXmas)

…but there is also abundant evidence of replies, long conversations of back and forth as Phelps-Roper argues her corner, breezily swapping jokes and telling people they were going to hell. In the book she describes how she formed relationships with a handful of disparate people she engaged with over twitter, not people she agreed with, but people who seemed willing to engage the person she was, beyond the beliefs that she espoused. Later, these relationships would be key in cracking the shell of her ideology.

I love a good news story, and social media needs positive press. For all you hear about echo chambers, the research seems to suggest that people have broader networks, ideologically, on social media than they do offline. This is so much more true for someone in Phelps-Roper’s position. Social media provided connections outside of her family and Church. These connections existed long before she left the Church, and you have to admire the people who put energy into them, for what may have been years with no seeming prospect of changing Phelps-Roper’s beliefs. Only in retrospect can their value and importance be seen.

* * *

Reading Unfollow, we can try and draw some general lessons about transformations in people’s deeply held beliefs.

The account of belief change in Unfollow doesn’t follow a simple cause-effect model. Conversion or de-conversion isn’t like one domino hitting another, but more like a complex system which adjusts to increasing pressures without showing external changes for a long time and then suddenly snaps, moving into a new configuration. You can’t predict the trigger event, any more than you can predict an earthquake (although with both belief change and earthquakes we might hope to figure out the general causes, the fault lines that make shifts more likely).

Her account shows clearly that beliefs are both emotional, and intellectual, and social objects. The Westboro Baptist Church of Phelps-Roper’s upbringing was all of this in spades, each element reinforcing the other. Changing beliefs required different circumstances on all fronts: emotional changes due to the behaviour of the Church, social changes in the dynamic of the Church families, but also intellectual changes due to the ideas Phelps-Roper was wrestling with. Trying to reduce her conversion to just one element won’t make sense. The ideas matter, but so do feelings, faith and family.

It’s also clear that the timescales for this change are long. Although there is an electrifying account of the very moment when the possibility of the Church being in the wrong solidified in her mind, Phelps-Roper recalls doubts she had decades before she came to this moment. Fleeting unease about the unfalsifiability of doctrine, noting the contradiction between some Church beliefs and scripture, revulsion over the basic horror of one particular passage of the bible (Judges 19-21). these cognitive/emotional reactions fed into the eventual earthquake of belief change, when it came.

The final lesson I take from Unfollow about belief change is the importance of internal factors, about the change being generated by the reasoning processes of the person undergoing the conversion. We talk a lot about how people’s beliefs are changed, strategising and theorising about how to influence others, but the account in Unfollow puts the person holding the beliefs absolutely at the centre. Phelps-Roper describes the events and circumstances that led to her radical beliefs, and to her change of heart, but ultimately the change came from within her, because of some basic drive in her personality to ask these questions.

Unfollow reminded me of this Forster quote

I believe … in an aristocracy of the sensitive, the considerate and the plucky. Its members are to be found in all nations and classes, and all through the ages, and there is a secret understanding between them when they meet.

Phelps-Roper was able to overcome the barriers to change erected by a lifetime - by a family, a micro-society, backed by the threat of Hellfire - because of a restless, inquiring, mind and a basic joy in life and engaging with ideas and other people. We all have this capacity. Although Unfollow is an intensely personal story, in this way it also has a hopeful message for the rest of us.

Miscellaneous links and readings follow

More on Phelps-Roper

Interview by David McRaney: What we can learn about dialogue, persuasion, and change from those who have turned away from extremism (highly recommended)

The Author on twitter: @meganphelps

Author website: meganphelpsroper.com/

INTERVIEW: FLASHPOINTS #3: How can we tell if a leader is irrational?

Ian Leslie e-interviewed me on this topic in his newsletter, gently encouraging me to comment on how we talk about Putin’s motives and hopefully also sharing something general about how to think about rationality (and why this newsletter is named “Reasonable People” not “Rational People”)

PAPER: A values-alignment intervention protects adolescents from the effects of food marketing

I’ve not read this for results reliability, but the basic idea illustrates the idea of reframing (RP#27) - and how it connects to existing values. Rather than try and convince adolescents to avoid junk food so they are healthy, Christopher J. Bryan and colleagues trialled an intervention which focussed on autonomy (from adult manipulation by junk food adverts).

From the abstract:

…we counter this influence with an intervention that frames manipulative food marketing as incompatible with important adolescent values, including social justice and autonomy from adult control. In a preregistered, longitudinal, randomized, controlled field experiment, we show that this framing intervention reduces boys’ and girls’ implicit positive associations with junk food marketing and substantially improves boys’ daily dietary choices in the school cafeteria. Both of these effects were sustained for at least three months.

From a 2021 talk abstract on the topic, Bryan says this about the research

Most public appeals to engage in such “should” behaviors (e.g., exercise, eat healthily, save for the future, conserve energy) focus on the pragmatic reasons why those behaviors are important. The problem with this approach is that such pragmatic appeals lack the motivational immediacy to drive the needed changes in behavior for reasons psychologists have understood for decades. Here, I suggest an alternative approach: reframing should behaviors in terms that emphasize how those behaviors serve the values that are already immediate and important to the people whose behavior one seeks to change

Bryan, C. J., Yeager, D. S., & Hinojosa, C. P. (2019). A values-alignment intervention protects adolescents from the effects of food marketing. Nature human behaviour, 3(6), 596-603.

PAPER: Fighting misinformation or fighting for information?

Argues that the problem of outright fake news is so marginal that any mitigation measures will, almost by definition, have small effects. It is more important, therefore, to focus on establishing trust and acceptance of reliable information

Acerbi, A., Altay, S., & Mercier, H. (2022). Research note: Fighting misinformation or fighting for information? Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 3(1)

NON-REPLICATION: No Illusion of explanatory depth in political views

Or, perhaps: using the illusion of explanatory depth to reduce extremism isn’t as straightforward as previously presented.

PODCAST Elizabeth Anderson & Talking to the Other Side

Link: Elizabeth Anderson & Talking to the Other Side

From “The Philosopher and the News” podcast, Elizabeth Anderson on what pragmatist philosophy has to offer the discourse.

I'd get "marginalise conflict entrepreneurs" printed on a t-shirt, except that according to Anderson this would be identity expressive discourse, and so a bad thing

PAPER: Fostering climate change consensus: The role of intimacy in group discussions

Groups given instructions which fostered intimacy had more effective discussions (more consensus, more belief change) that those told to focus on information. Another entry for the social-emotional-intellectual model of rationality.

van Swol, L. M., Bloomfield, E. F., Chang, C. T., & Willes, S. (2022). Fostering climate change consensus: the role of intimacy in group discussions. Public Understanding of Science, 31(1), 103-118.

And finally…

A cartoon for everyone with too much to do, from FowlLanguageComics

END

Thank you, Tom, for this piece about Megan Phelps-Roper's and the Westboro Baptist Church. I read this immediately after reading Anne Applebaum's piece in the Atlantic, There Is No Liberal World Order, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2022/05/autocracy-could-destroy-democracy-russia-ukraine/629363

The two pieces seem to fit remarkable well together. Reading your article, it felt like I could apply it to Russia simply be changing a few words. Taken together with Anne's description of freedom in the first paragraph it gave an insight into one of the ways that Russia is different from the Western world and why many still support Putin. The contrast also raises a far more subtle question. By making the link with authoritarianism in Russia it caused me to think about authoritarianism by individuals and groups within a democracy. At the most extreme I imagine an authoritarian liberal democracy; one that actively forbids authoritarianism. This is not comfortable reflection.

I have a nagging thought that a shared belief system is an integral part of a society. That variation on 'them' and 'us' are a human given an aspect of being human that makes a group strong, far stronger that other expect, but also one that some have discovered can be manipulated.

Taken together I think that these two articles express the challenge of our times.

Thank you Tom, great article!