Belief in the reasonableness of others

Reasonable People #57: Developing a measure of our faith in reason, new work from me

The twin suns of this newsletter are that people are often far more reasonable than they have been portrayed, and that what we believe about human reasonableness matters.

I’ve been thinking about that second part. If what we believe about human reasonableness matters, it should be possible to capture that for individuals, or particular populations, to measure it and understand something about the cluster of attitudes and beliefs that are downstream. Is faith in the reasonableness of others part of general support for democracy? Does it protect you from conspiracy theories?

If that’s true, it would be nice to know. And if it’s not true, it would also be nice to know (in the sense of ‘nice’ that is “we are meant to be open to being proved wrong about things”).

Back in 2022 I went looking to see if there was an existing measure for belief in the reasonableness of others; a set of survey questions which we could add up the answers to in order to quantify people has having high, or low, or middling faith in the reasonableness of others. As I wrote in the newsletter, I didn’t find anything which was exactly right. There are measures of a belief in a just world, of generalised trust of other people, of cynical beliefs about human nature, but nothing which tapped this specific idea that we are reasonable - strive for consistency, follow evidence, admit when we’re wrong, resist manipulation, and so on.

Psychologists have a well-known toothbrush problem with their theories and their associated measures - everyone wants their own, nobody wants to use anyone else’s. To avoid contributing to this, I was really hopeful someone had already developed a measure which captured the ideas I was interested in, but I just couldn’t find it.

Ok, I thought, maybe I could invent a new measure to quantify the belief in the reasonableness of other people. The initial efforts to do this are reported in our newly minted preprint Quantifying belief in the rationality of others: the Faith in Reason scale, co-authored with Kate Dommett and Junyan Zhu.

So, how do you invent a new measure in psychology? Well it seems their are two basic approaches. The first approach is that you can rigorously review the existing literature, develop a conceptual framework which defines your concept of interest, develop and refine individual questions (“items”) which probe aspects of this concept, then add or drop items to ensure you are efficiently measuring something which is both statistically coherent and which cleaves to the real-world aspects of the thing you hoped to measure. This last aspect is particularly tricky and called the problem of ‘external validity’. It is easy enough to invent a measure which looks like it is measuring a real thing - for example, people are consistent in how they answer it - but it doesn’t relate at all to the particular real thing you set out to measure. Imagine I want to measure people’s tendency to eat more crisps when they really shouldn’t. I could have a scale with questions like “Are you going to eat more crisps?” and it would look superficially plausible, but that doesn’t go far in ensuring it would have any validity as a measure of whether people actually eat more crisps when they are sat down with idle hands and a bowl of crisps in front of them. You could score high on my fictional “I definitely won’t eat more crisps” measure and still be the type of person who stuffs their face. It would be a measure with low external validity. (There’s a well developed science for developing measures. There are references in our report, but a good place to start is Flake & Fried, 2020).

That’s the first approach to measurement development. It sure is a lot of work, which is why second approach is so popular : just invent some items, throw them at participants and assume you’re measuring what you hoped to measure.

I’m no expert at this, but I thought I’d at least aspire to the first approach.

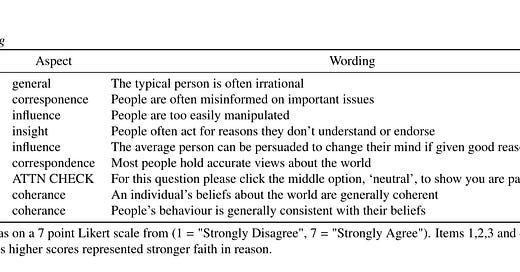

First off, theory. Rationality and reasonableness1 are richly debated, but core aspects include ‘correspondence’ (what the reasonable person believes matches the external world) and ‘coherence’ (the reasonable person’s beliefs are consistent with each other). Along with these an insight into the nature of your own beliefs is core to reasonableness, and an ability to modify them for the right reasons circumstances (and resist modifying them for bad reasons). Let’s call this last core idea that of ‘influence’. There are references in the preprint. You might ask at this point if these things necessarily go together - when people think of reason are they thinking of these aspects in some sort of collective aspect, in which the components track or trade-off against one another. Well, developing the measure with these items is one way of finding out.

Next, I invented question wording which tried to tap these aspects, in ways that were positively and negatively framed. Here’s what I came up with.

Then we asked the items of a representative sample of nearly 2000 UK voters (who were were surveying anyway), and got some data which allows analysis of these items.

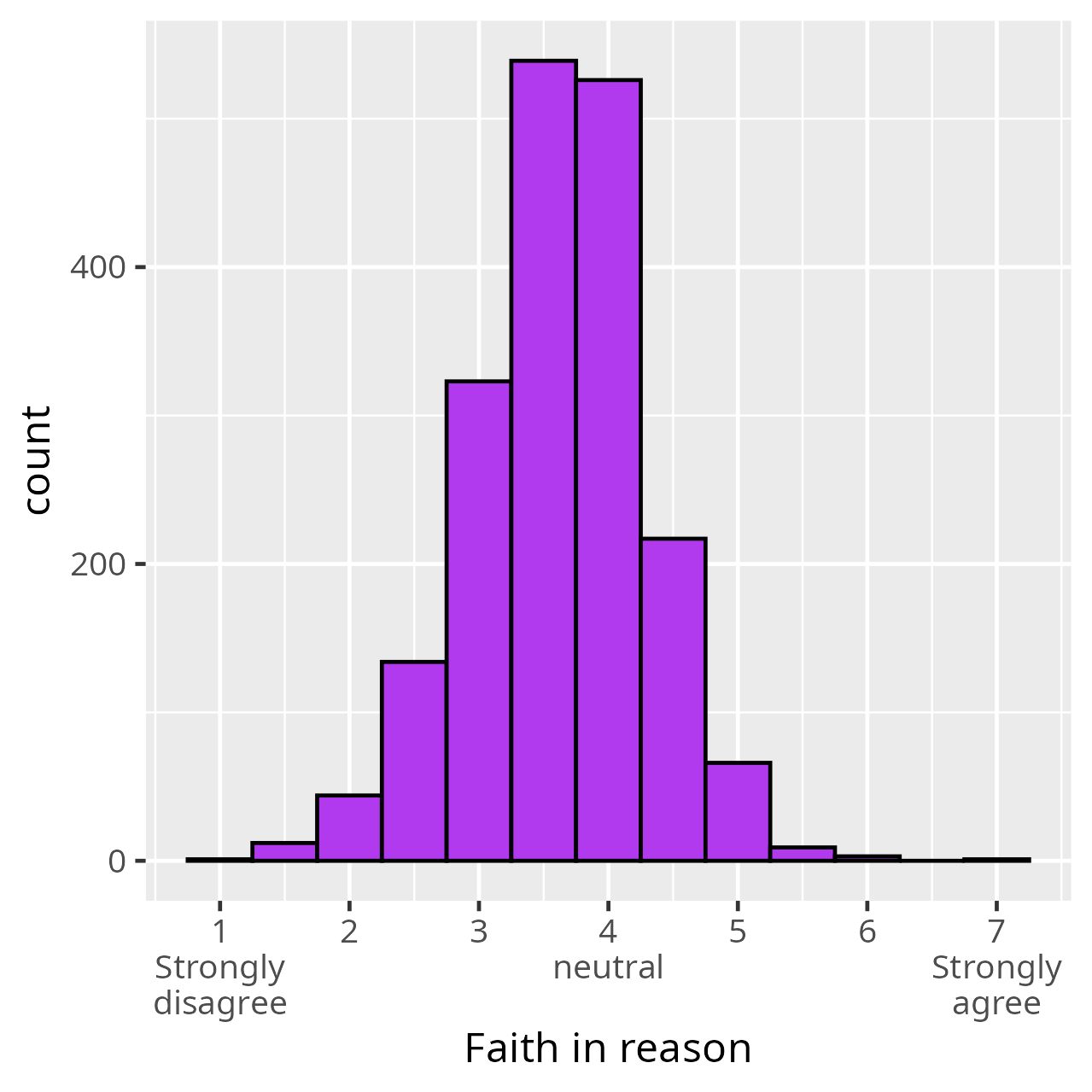

First off, the scale - a single number constructed from answers to all items so higher numbers represent stronger faith in reasons - shows a good variation. Some people really did say that they had faith in the reasonableness of other people. Other people really didn’t.

The average response was just slightly under the neutral point of 4, meaning that the typical score reflected a slightly more pessimistic than optimist view of human reason.

Next, I tried various analyses which attempt to work out if the different items form a coherent set2. They all said ‘maybe’, so I marked this as “to be revisited”. Clearly I could refine the items to make them form a more coherent set and/or pick our different aspects of rationality more distinctly.

Finally, I asked asked participants some other standard measures that political and social scientists ask in surveys. One was about the perceived importance of democracy (“How important is it for you to live in a country that is governed democratically?”), which didn’t correlate in any way with my faith in reason scale. Suggesting either that attitudes to democracy are independent of responses to my scale, or that there was a ceiling effect where most people said democracy "Very important” and so there wasn’t much meaningful variation.

Another standard measure I used was “generalised trust” which is a single item which asks people “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted?”. This correlated moderately, but not completely with my measure. Does that mean the two concepts are related to each other - perceptions that other people are trustworthy supporting the perception that other people are reasonable, and vice versa ? Maybe! In addition, that they don’t correlate 100% at least suggests to me there is also something distinct in “faith in reason” separate from generalised trust.

So what does all this mean? Some modest conclusions are that it may be possible and sensible to try and quantify a person’s attitude to the reasonableness of others, in this way, and that the measure may reflect some small part of a wider constellation of attitudes which are of interest, such as generalised trust.

I submitted the report to the Cognitive Science 2024 conference and it was rejected, with fair and thorough reviews. One reviewer suggested some changes to the item wording which would be improvements, another suggested making clearer that the analysis is exploratory. After sitting on the manuscript, making some small improvements, I’ve now published the report as a preprint, but probably won’t re-submit to a journal or conference. These analyses are preliminary, and I think I have some follow up work which both improves on the scale, and demonstrates it’s relevance in an interesting way. Of that, more soon.

For now, I’m happy to share where I got to with this, and hear any feedback.

Here is the conclusion from the preprint:

The nature of human rationality is a perennial concern, both in terms of what it means for our self-regard and societal projects like democracy. Recent concerns over misinformation have amplified these concerns, and often assumed a pessimistic view of human credulity and bias. Nonetheless, extensive evidence supports measured optimism about human rationality - that the capacity for due skepticism, warranted trust, and reason responsiveness is widespread (Mercier, 2020; Nyhan, 2020). Responses to our survey appear to reflect these competing currents, with some endorsing extremely pessimistic views of human reason, other endorsing extremely optimistic views, and the majority represented in the middle. It remains to be seen how future world events and the dissemination of empirical results from the cognitive sciences might affect the population levels of Faith in Reason.

References

Preprint: Stafford, T., Zhu, J., & Dommett, K. (2024, December 31). Quantifying belief in the rationality of others: the Faith in Reason scale. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/umwxj

I wrote the preprint as a “reproducible manuscript”, using R and Rmarkdown so that when the manuscript is compiled to PDF it also runs the analyses, integrating the data, code and text in a master file, sitting in a folder which captures all the project materials. I think this is pretty cool, but nobody I work with is as excited about this as I am. You can see the files here: https://github.com/tomstafford/faithinreason/.

The newsletter where I first raised the idea of constructing a scale : RP#30 Quantifying our Faith in reason

Flake, J. K., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Measurement schmeasurement: Questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 456–465.

Preprints?!

Speaking of preprints, I’m a big fan (and also on the Scientific Advisory Board for PsyArxiv, the preprint server for psychology, so count that as a conflict of interest).

Here’s a two minute explainer I wrote in 2018, in case the idea is new to you: Open Science Essentials: Preprints

And a Christmas hobby project, which shows the level of activity on PsyArxiv and the most downloaded papers: https://mastodon.social/@PAXscraper

Individual reports of new preprints here: https://mastodon.social/@PsyArXiv

PsyArxiv Blog: https://blog.psyarxiv.com/

And finally…

No cartoon, but a painting from 1882 by John Atkinson Grimshaw, ‘Moonlight’ (possibly painted in his native Leeds?)

END

Comments? Feedback? Genuinely I’d like to hear any way of improving the scale, it is still in development. I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

I am going to use the two interchangeably, partly because I don’t think anyone has a clear idea of what rationality is, at root.

There are detailed in the report, but, briefly, these were the traditional way (cronbach’s alpha and factor analysis; Mokken scaling from item response theory; and Exploratory Graph Analysis

I think the measure is a great idea and I appreciate the time and care you took to communicate your approach and the thinking behind it.

My first thought is that it makes me curious about how our perception of the reasonableness of others depends on our perception of their willingness to inquire and bend, their amiability , curiosity, and openmindedness, vs. their perceived capacity to reason consistently and accurately.

I suspect that our view of what it takes to reason together has a distinguishing line between “people who reason well are good at logic and at remembering and using factual knowledge and have high cognitive abilities,” and “people who reason well are curious and willing to listen to others and explore and seek new patterns.”

Seemingly both are important factors but there seem to me to be important individual differences in how much weight we give those factors. Many stereotypes are based on that sort of distinction and usually where there are persistent stereotypes there is at least a perceptual reason for them.

How much we care about precision and accuracy of thinking and how much we care about exploratory thinking and accommodation to others seems to me to shape how reasonable we see others. Whether we see accommodation as mere compromise for example. Or whether we see precision and diligence as rigid formality.

Maybe it's linked to empathy in which case specific relatedness would make a big difference compared with a more abstract concept. Is aunt/cousin/friend rational vs is neighbour at the end of the street vs top politician? Relatedness could lead to both overestimating and underestimating rationality compared with overall views.