Conspiracy thinking

Reasonable People #29 how we measure conspiracy theory beliefs, and the vulnerabilities to confusion thereby introduced. Look away now if you don't want to see how the sausage is made.

Conspiracy Theories are a dark mirror to our rationality. Out of reasonable attempts to understand the world, to discern the causes of things, some people construct fever dreams of UFOs, Illuminati-signs and secret rulers.

Yet it is hard to put the finger on what exactly is wrong with conspiracy theories. It isn't that they are contradictory - they are often maddeningly internally consistent. Nor is it that they don't explain. They provide reasons why events occurred exactly as they were supposed to. Any reasonable person will also point out that conspiracies do sometimes happen, so even that can't be a hallmark of the conspiracy theory.

Quassim Cassam notes that having an explanation for 9/11 which invokes a conspiracy by a secretive group (the Al Qaeda terrorists) is a belief which, even though it is a theory about a conspiracy, isn't enough to count as a Conspiracy Theory. The true Conspiracy Theories about 9/11 contain extra elements - doubt of the official narrative, belief in a plot wider and more sinister than Al Qaeda's.

But what of the Conspiracy Theorist? What epistemic sin does one commit to fall for conspiracy theory? There's a growing scholarly industry in attempting to measure conspiracy theory beliefs, and the conspiracy theory mentality that leads you to fall for them.

* * *

One approach is to ask people about specific conspiracies: is the government hiding evidence of alien contact? Was 9/11 an inside job? Was covid deliberately released as part of a government plan? This has the appeal of the concrete - we all know what we are talking about. Do this and you find out two important facts: a large proportion of the population endorse at least one conspiracy theory, and people who endorse one conspiracy theory are more likely to endorse others.

Asking about the specifics has limitations. What about the conspiracy theories you don't ask about? Maybe the proportion of the population who endorse at least one conspiracy is far higher, if only you knew to ask about the right beliefs. In addition, the focus on particular theories seems to keep the general, deeper, issue at bay: the urge to conspiratorialism. What if there is something beyond the details of specific conspiracies, something about the style of thought in those who believe in Conspiracy Theories?

* * *

Another approach is to try to get at conspiracist thinking in general, not just ask about specific conspiracies. This is what Brotherton, French & Pickering (2013) did. Theirs is one of the most popular scales in the study of conspiracy thinking, the GCBS (Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale). Here are the 15 items

I’ve always been interested in how facts are made, and this is a good example of the business of fact-making in academic psychology. We want to know how conspiracy theorists think, so we invent a scale to measure that, and then we try and understand the things which predict high scores on the scale. In the process, there’s a kind of bait and switch, as the object of study changes from the vague concept which has everyday currency into a more narrow, scientific, object. We start with Conspiracy Theories and those who believe them. We may not be able to define a conspiracy theory, but we feel like we know it when we see it. With the deployment of the GCBS we tie the concept down to a single metric - how high you score on the scale. No problem with this, of course, as long as you remember that when we talk about Conspiracy Theory beliefs, as measured by the GCBS, we are talking about survey respondents’ tendency to endorse these specific questions.

A moment to look and you can see that some of the items are more reasonable to endorse than others. You might reject

#8 Evidence of alien contact is being concealed from the public

But who doesn’t have some sympathy for

#15 "Information is deliberately concealed from the public out of self-interest"

Or even

#11 "Groups of scientists manipulate, fabricate, or suppress evidence in order to deceive the public"

… ?

It is worth remembering if you see a study claiming that Conspiratorial Thinking is associated with X and Y, that the use of a scale like this makes conspiratorial thinking a continuum which we all exist on.

Another popular scale makes this even clearer. The Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire (CMQ, Bruden et al, 2013) has five items, to which you indicate the extent you agree:

I think that…

1 … many very important things happen in the world, which the public is never informed about.

2 … politicians usually do not tell us the true motives for their decisions.

3 … government agencies closely monitor all citizens.

4 … events which superficially seem to lack a connection are often the result of secret activities.

5 … there are secret organizations that greatly influence political decisions.

#3 particularly (“government agencies closely monitor all citizens.”) looks much more reasonable following the revelations about the extent of NSA spying in the US.

The effort to focus on some essence of conspiratorialism, abstracted from any specific conspiracies, led Karen Douglas and colleagues (Lantian et al 2016) to suggest a 1 item measure:

“I think that the official version of the events given by the authorities very

often hides the truth.”(scored on a scale from 1 = Completely false to 9 = Completely true)

The purist in me loves this, but you have to wonder what these scales lose in their quest for abstraction.

One worry is that in making a scientific object - Conspiratorial Thinking - these scales make these beliefs pathological. The idea of Conspiracy Theories borrows normative connotations - we can’t define a conspiracy theory exactly but we know it is a Bad Thing - and those connotations persist when we switch in a scale which operationalises the definition, but in a way that captures defensively reasonable beliefs.

* * *

And so it was a delight to read Stojanov & Halberstadt’s (2019) ‘The Conspiracy Mentality Scale: Distinguishing Between Irrational and Rational Suspicion’. They write:

"there still exists no validated measure of the general tendency to believe in conspiracies, abstracted from both the content of specific conspiracy theories and from the rational skepticism that serve democracies well. This paper presents the development of such a scale."

Their questionnaire has two subscales. First, items which measure conspiracy mentality (which they label Conspiracy Theory Ideation, CTI). Here are the items:

CTI_1. The alternative explanations for important societal events are closer to the truth than the official story.

CTI_2. The government or covert organizations are responsible for events that are unusual or unexplained.

CTI_3. Many situations or events can be explained by illegal or harmful acts by the government or other powerful people.

CTI_4. Some things that everyone accepts as true are in fact hoaxes created by people in power.

CTI_5. Events on the news may not have actually happened.

CTI_6. Many so called “coincidences” are in fact clues as to how things really happened.

CTI_7. Events throughout history are carefully planned and orchestrated by individuals for their own betterment.

The items which measure reasonable skepticism are:

SK_1. Many things happen without the public’s knowledge.

SK_2. There are people who don’t want the truth to come out.

SK_3. Some things are not as they seem.

SK_4. People will do crazy things to cover up the truth.

This first paper makes a case that the two subscales are separate, coherent, reliable and meaningful measures. A second paper (Stojanov, Bering, & Halberstadt, 2020) uses the scale for some follow up experiments. It has open data, which I love, so I made this plot of responses, from participants in their study 6 (n = 605).

This shows that although the skepticism and conspiracy theory ideation subscales are somewhat correlated, there is a lot of independent information in the two measures (some people are low on conspiracy theory ideation, but high on skepticism; some people who are at least moderate on conspiracy theory ideation are low on skepticism).

* * *

One of the most consistent findings from the study of conspiracy beliefs is that people holding them have low trust. Low trust in other people generally, but also low trust in establishment institutions such as the government or the University employed scientists.

The interpretation of this association with low trust changes if measures of conspiracy theory beliefs confound conspiratorial beliefs with reasonable skepticism. There’s two ways this could happen. First is that some of the items in some of the scales used reflect skepticism rather than conspiracy. Stojanov & Halberstadt’s contribution is to make this explicit. Other scales are not so careful. The second way this could happen is if, while the questions ask about conspiracies, people’s answers reflect other attitudes beyond their actual commitment to specific conspiracies. So, for example, I ask “Do you believe the government has covered up evidence of alien contact” and part of your answer may reflect a general attitude of “screw the government, those guys are definitely lying to us” and not a strong belief in aliens. (So called expressive responding).

Confounding - whether in the measure or due to expressive responding - may explain some salient sociological findings about conspiracy theories. There are elevated levels of conspiracy belief among ethnic minorities (e.g. this paper), and, cross nationally, higher levels of conspiracy belief in countries with a recent history of authoritarian government. Both populations have justifiable reasons to distrust the official story, so we shouldn’t leap to label them irrational victims of conspiracy theories. Just by virtue of their distrust of the government line they will score higher on common measures of conspiratorial thinking.

* * *

Creating scales of conspiratorial beliefs puts everyone on the spectrum. Although this is arguably a great strategy for understanding the psychology of conspiratorialism, it makes us vulnerable to over-emphasising the importance of conspiracy theories

There's already a risk of this because Conspiracy Theories are so colourful (And, honestly, who doesn't have some small hope that an interspace species of lizard people run the world, rather than the appalling crowd of perfectly ordinary humans we appear to be stuck with). When our measures confound real commitment to these beliefs with expressive responding and reasonable skepticism, both reflecting distrust of the establishment, it encourages us to focus on Conspiracy Theories as a bigger problem than they really are.

How big a problem are conspiracy theories? It isn’t clear. With our own work on vaccines (Brand & Stafford, 2021) we found that a UK population of vaccine hesitant adults didn't spontaneously express commitment to conspiracy theories to explain their reluctance to get vaccinated. Instead, like other work on covid-vaccine resistance, we found that attitudes to the vaccine were mixed, with some reasonable concerns about the safety and necessity of vaccines ("reasonable", in the sense that it makes sense to ask yourself these questions, even if vaccine rejectors reach different answers than that of the consensus view).

Anti-vax conspiracy theories are a long tradition, with a hardcore of true believers (who are protected from the consequences of their mistake by the herd immunity the rest of us provide). Obviously this tradition must fuel some vaccine hesitancy in the wider population, but it isn't clear how much (and how would you even tell?). It's fun to fact-check anti-vax nonsense, but it will be a distraction if we let the boogeyman of a Conspiracy Theorist stand in for the reality of the mass of unvaccinated who are merely hesitant, or even just underserved by vaccine provision, rather than actively resistant.

Scroll down for more on conspiracy theories, scale development and the joy of open data published alongside studies.

References

Brand, C. O., & Stafford, T. (2021, December 17). Covid-19 vaccine dialogues increase vaccination intentions and attitudes in a vaccine-hesitant UK population. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/kz2yh

Brotherton, R., French, C. C., & Pickering, A. D. (2013). Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: The generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Frontiers in psychology, 279.

Bruder M, Haffke P, Neave N, Nouripanah N, Imhoff R. Measuring individual differences in generic beliefs in conspiracy theories across cultures: Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. Front Psychol 2013;4: 279. PMID: 23734136 28: 617–625.

Lantian A, Muller D, Nurra C, Douglas KM. Measuring belief in conspiracy theories: Validation of a French and English single-item scale. Int Rev Psychol 2016; 29: 1–14.

Stojanov, A., Bering, J. M., & Halberstadt, J. (2020). Does Perceived lack of control lead to conspiracy theory beliefs? Findings from an online MTurk sample. PloS one, 15(8), e0237771.

Stojanov, A., & Halberstadt, J. (2019). The conspiracy mentality scale. Social Psychology (2019), 50(4), 215–232 https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000381

the journal site tries to charge 20 Euros for the PDF, but I found this link which may work for you

Elsewhere

Mindhacks.com (2017): Conspiracy theories as maladaptive coping

Paper: Believing in nothing and believing in everything: The underlying cognitive paradox of anti-COVID-19 vaccine attitudes.

Newman and colleagues write

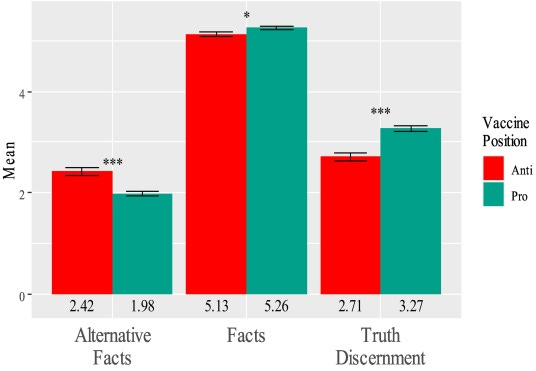

"We found that people who rejected COVID-19 vaccines believed well-established facts less, and “alternative facts” more ...Less discernment between truths and falsehoods was correlated with less intellectual humility, more distrust and greater reliance on one's intuition. "

BUT, as is my habit, I have to point out that the study provides resounding evidence that vaccine-refusers *can* discern true from "alternative" facts. Yes, there is a difference between pro and anti-vax, but that is a difference on top of the basic pattern where the average person rates true facts as true and false facts as false.

To see this, check out their Figure 1, showing mean "perceived veracity" on a scale of 1 to 6. Note true facts perceived as massively more true than alternative facts, in both groups. (The two right bars are the difference measure)

Nonetheless, the choice to refuse the covid-vaccine is an important difference between people, so I’m down with the rest of the paper which investigates the other factors associated with being pro-vs-anti vaccine.

Fitting with the rest of the literature, Newman et al find that pro and anti vax groups are significantly different in levels of trust. But a larger difference between the groups than extent of trust, is the difference between the pro and anti-vaccine groups in conspiratorial thinking. Conspiratorial thinking is also the strongest correlate of weak discernment of true from false facts (see their Table 1, but weirdly this is omitted from the abstract).

That the conspiracy theory endorsement correlates with failure to discern true from false facts suggests that high scores on the conspiracist scale are not merely expressive responding (e.g. not just a more sensitive measure of distrust), but part of the wider cognitive/belief system.

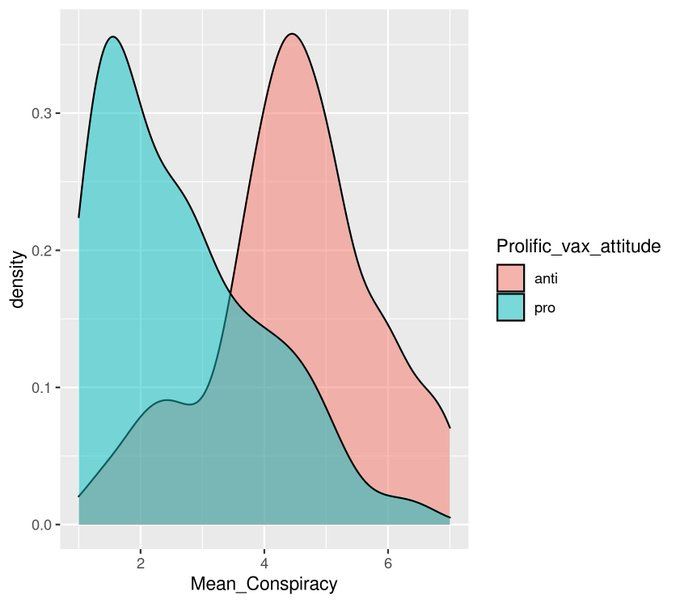

To visualise the extent of the difference between the pro and anti groups in terms of conspiracy endorsement, I took the study data and plotted the distribution of conspiracy theory endorsement. The conspiracy theory scores come from the Brotherton GCBS measure (the 15 items shown above). The vaccine attitudes are provided by the survey platform Prolific which asked people a bunch of questions, including it seems vaccine attiude, before recruiting them to specific surveys. This is great because it means you can target particular populations without worrying that people are pretending to belong to particular groups just for survey-cash.

Anyway, look at the difference in distribution of the mean score on the GCBS conspiracy scale, for pro and anti vax groups. Now that's an effect size! Far higher conspiracy thinking in the anti-vax group (but see the caveats about the scale mentioned above)

The study conclusion notes that studying people’s current beliefs doens’t reveal the causal directions between low trust, conspiracy endorsement and anti-vaccine attitudes. We need to investigate how people develop anti-vaccine attitudes (and how they get into conspiracy theories), and how they get out of them. Strong agree with this: [there is a] “vital role of trust as a path to restoring the shared reality we all depend on.”

Newman, D., Lewandowsky, S., & Mayo, R. (2022). Believing in nothing and believing in everything: The underlying cognitive paradox of anti-COVID-19 vaccine attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 111522.

Open data and code: https://osf.io/wjpz4/

Some more graphs of the open data in this thread

Conspiracist Ideation: scale validity

Anyone can make up some random questions and call it a scale (and in psychological science, they frequently do). Checking that the questions measure what you want, and only what you want, that people give consistent answers (both over time and consistent with their other answers) is … less often done.

The authors cited above do some of this work, but checking that these measures work as intended is an ongoing job. If you want to read more about this, two good papers are:

Swami, V., Barron, D., Weis, L., Voracek, M., Stieger, S., & Furnham, A. (2017). An examination of the factorial and convergent validity of four measures of conspiracist ideation, with recommendations for researchers. PloS one, 12(2), e0172617.

…which has a good survey of the most popular measures of conspiracy theory beliefs (and concludes that most of them are mediocre in terms of scale validity), and

Drinkwater, K. G., Dagnall, N., Denovan, A., & Neave, N. (2020). Psychometric assessment of the generic conspiracist beliefs scale. Plos one, 15(3), e0230365.

…which looks at the Brotherton / GCBS scale (and says it is ok)

Part of the interest in this kind of analysis is not just understanding if the scales are good measures, but what structure people’s answers have. Understand this, and we might see if the beliefs of conspiracy theorists are organised around a single, central, belief (something like “nothing is as it seems and everything is connected”) or whether there is looser network of mutually reinforcing but separate beliefs (openness to the idea of an alien cover up makes 9/11 being an inside job more plausible. And it was the same people who killed Diana of course…etc).

Network analysis seems promising here, with a new analysis from Matt Williams and team supporting the network account (I don’t understand the technique well enough, but I do wonder if a network analysis was ever going to deliver any other conclusion)

Williams, M. N., Marques, M. D., Hill, S. R., Kerr, J. R., & Ling, M. (2022). Why are beliefs in different conspiracy theories positively correlated across individuals? Testing monological network versus unidimensional factor model explanations. British Journal of Social Psychology.

Open materials: https://osf.io/y3rfz/

And finally….

Reading about the different scales published for measuring conspiracy theory beliefs reminded me of the XKCD cartoon ‘Standards’

And the old line that in Psychology, theories are like toothbrushes: everyone has one, nobody wants to use anyone else’s.

I find the whole concept of conspiracy theories baffling. There’s the stuff that is quite clear (flat earth...) but what about climate skepticism? Some « mainstream » theories (the wilder claims of some gender theorists spring to mind) surely qualify as being totally anti-science yet no one calls them conspiracy theories. One thing that I find interesting is that people who oppose a mainstream theory often oppose more than one. Not sure what it means.

Many thanks for an interesting post on conspiracy theories. While it is interesting to have a digest of some work on this subject I have some observations.

First is the rather thorny question of what is a conspiracy theory. I would expect a definition that would differentiate a conspiracy theory from other aspects of shared belief, beliefs that are not a conspiracy theories. I strongly suspect that such a definition would be exceedingly difficult or impossible and that suggests that the attention should be turned elsewhere. Using the example in the blog there are some that belief that vaccines are not beneficial but rather form a risk whereas there are others that believe that they beneficial and worthwhile; which is the conspiracy theory.

My second observation is that most, though not all, of the questionnaire items refer to groups; secret organisations, government, the public, etc. To me this points more to group behaviour rather than conspiracy theories as such. I had hoped to see an exploration of group formation, utility and behaviour as a way of exploring conspiracy theories. I feel that the academic psychology is bedevilled by efforts to come up with something new rather that like to and evidence the best - most enduring - theories of human behaviour.

While I have not read the papers referenced and therefore have not read the theoretical basis for the questionnaire construction it does appear to me that the attempt to create 'conspiratorialism' as a separate psychological concept diverts attention of linking such behaviour to existing theories, group behaviour, cognitive dissonance, self-determination to name a few, which may provide more greater illumination that simply creating yet another scale.

My final musing on this piece is the motivation for conducting research (surveys wrapped in a scientific wrapper) in the first place. Is it, I wonder, simply to meet the publish imperative or is it to find a way to prevent or counter such theories? The latter carries with it the assumption that the psychologist knows better what people should believe and the whiff of manipulation of coercion to bring such people into line with proper beliefs? Just because that my belief is right and I have the science to prove it does not mean that those who do not believe it are wrong. I reflect on the basis of modern science - that all findings are provisional and tentative until disproved.