Democratic Reason

Reasonable People #16: Hélène Landemore's argument for the cognitive, not just moral, superiority of democracy

In Democratic Reason: Politics, collective intelligence, and the rule of the many, Hélène Landemore seeks to give an epistemic justification for democracy. This is an argument that democratic government is not just more just or fair, but also that it is smarter - that it allows better collective decisions. Just how this is possible, and why we should believe it actually is the case is the subject of this book.

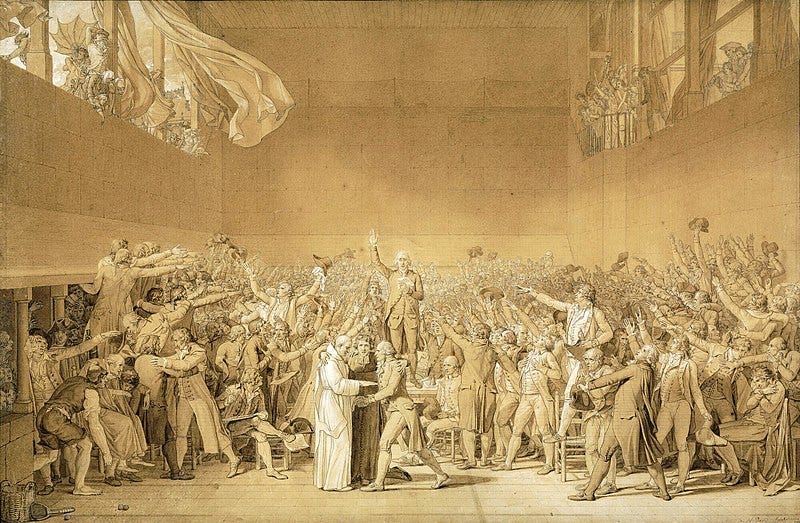

Image credit: Le Serment du Jeu de paume, by Jacques-Louis David

To convince us that democracy is smart, Landemore has to deal with the manifest fact that many of us are not smart. Not only are there the cognitive biases that psychologists know and love, but there is a whole literature in political science about the ignorance of voters regarding both aspects of government and about the specific social issues which government deals with (e.g, things like possessing false beliefs about the number of migrants coming into the country, not knowing who the prime minister is, etc). How can dumb citizens make smart governments?

Part of the response to this is that the stupidity of the average person has been over-emphasised by psychological research, but more central to Landemore's argument are claims about the nature of collective intelligence. Here, she argues, for complex problems - such as the ones that beset society - it is more important that the group members are different from each other in how they think and what they know, rather than the sum of their individual smarts being as high as possible. This is the Diversity Trumps Ability theorum. The claim is that however smart a dictator or elite cabal is, their ability, in the long-term, to produce smart decisions is rendered inferior to that of the univerally-inclusive decision making group which is democracy.

Deliberation drives the emergence of collective intelligence

Two key aspects of this collective intelligence argument are a) democratic reason is an emergent property, distributed over many individuals and artifacts (such as institutions) and b) there is a cognitive division of labour. By focusing on the emergent level of collective action Landemore hopes to reconcile the apparent paradox between her claim that democratic choices can be smart and the ignorance and/or stupidity of individual citizens (or at least the ignorance/stupidity of the average citizen in comparison to the smartest citizen).

In economics/political science there is a technical literature on preference aggregation, and how individual choices (votes) can or cannot be counted to produce coherent (and preference-satisfying) collective choices. While Landemore does engage with this area, she emphasises that the value of majority rule is that it is preceeded by, and necessitates, deliberation.

Democratic deliberation has several important epistemic properties. It adds to the pool of ideas and information; it weeds out bad arguments and promotes good ones; it encourages consensus, by both promoting individuals' understanding (even if they are in the minority and remain in dissent). Perhaps most importantly for Landemore's argument, though, is that it is inherently inclusive - all citizens contribute, rather than an elite.

Does Diversity Trump Ability?

For the "diversity trumps ability theorem" Landemore draws on the work of Hong & Page (e.g. Some Microfoundations of Collective Wisdom, which I have not read so I draw on Landemore's treatment of it). Democratic Reason has some discussion of the conditions which must hold for collective diversity to be more important than collective ability in decision making (p102-3). These conditions are that:

Problems are hard (i.e. not easy to solve for any individual)

Group members are diverse (e.g. such as would be compromised by minimal groups, or groups picked from a homogenous population)

The ability of group members' is above some minimal threshold (to avoid local minima)

There is a diversity of members’ local optima (such that the global optima only is found in the overlap of members’ optima). Landemore describes this last requirement as being such that the best solution is obvious to everyone when they are made to think about it. (I don't see how this follows).

To this I would add a couple more requirements, which I think are assumed :

Transaction costs are low. If it is hard for group members to coordinate/communicate then decison making by small groups or individiuals will be favoured

Problems are complex, not just hard: there are multiple local optima / the fitness landscapes is rugged. I think this entailed by the forth of the original criteria Landemore describes, but I wanted to make it explicit. Rugged landscapes mean you can't reach solutions by incremental adjustment your first guess, merely improving on what you've got a little at a time. In rugged landscapes small improvements on subproblems can lead to descrements in the finsl outcome, there are unintended consequences, great solutions can be adjacent to terrible ones. Things are, in short, interesting.

So what reasons do we have that the problems which democracies seek to solve meet these criteria? For me, I think there is a plausible story about problem selection - any issues which have non-hard, non-complex solutions don't need the full epistemic abilities of the polis. By the same logic, political leaders only get hard choices, since any and all obvious choices are solved before they require an executive judgement call. So, analagously, perhaps we can find the Diversity Trumps Ability Theorum plausible. Not because it is always true, but because selection means it is most true for the issues for which it matters most whether it is true or not.

Elite vs Democractic Decision making

The strength of democractic reason comes out when we don't even know the correct way to frame a problem, let alone the solution. By its nature, democracy includes the broad population in decision making. This, Landemore argues, means it is inherantly better able to recognise, diagnose and define problems - the stage before their framing becomes established.

Conversely when we already have a clear framing of an issue, decision making is most likely to be technocratic. Then we will most likely want to devolve decision making to experts. If you have a broken leg you want a doctor, not a diverse group which represents the general population.

Perversely, well framed problems are those for which it is easiest to think of concrete examples, and so they are most likely to spring to mind, and so be used as tokens in debate over the problem role of elite vs democratic decision making. This means that discussion around the value of inclusion vs expertise in decision making is likely to orbit exactly the kind of examples which favour elite rather than democratic decision making.

Image Credit: Will McPhail

Democractic Reason

Democratic Reason is a lengthy, clear and scholarly argument which I cannot do justice to here. It contains detailed intellectual history of the ideas it discusses, as well as systemmatically making a case, whilst similtaneously setting out exactly what she is not claiming (or where her claims are not intentended to be relevant).

Five stars, strong recommend.

* * *

Landemore, H. (2017). Democratic reason: Politics, collective intelligence, and the rule of the many. Princeton University Press.

Hong, L., & Page, S. (2012). Some Microfoundations of Collective Wisdom. In H. Landemore & J. Elster (Eds.), Collective Wisdom: Principles and Mechanisms (pp. 56-71). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511846427.004

Illiberalism Isn’t to Blame for the Death of Good-Faith Debate

Smart take that we should talk about the effect of platform structure, and how the “argumentative hyperliteracy” of being Very Online affects debate. Too pessimistic for me - once you diagnose that the internet encourages counterproductive reactions, you are allowed to stop them.

The Conjunction Fallacy? Take a Guess. Kevin Dorst & Matt Mandelkern

In which they argue that a centerpiece of empirical evidence that people are irrational, because they make judgements which violate the laws of probability, is not such good evidence

although the conjunction fallacy is sometimes a mistake, it is not a mistake that reveals deep-seated irrationality. Instead, it reveals that when forming judgments under uncertainty, we need to trade off accuracy for informativity––we need to guess.

This fits in a tradition of claiming that the demonstrations psychologists evoke to ordinary people’s irrationality draw on a particular intepretation of how the test questions should be intepreted as much as analysis of people’s answers to them.

What are we to make of evidence that pairs and groups are less likely to fall for the conjunction fallacy? How about that the informativeness of answers becomes less of a priority when a group can confirm what is understood with each other? So the probability comes to the fore?

Charness, G., Karni, E., & Levin, D. (2010). On the conjunction fallacy in probability judgment: New experimental evidence regarding Linda. Games and Economic Behavior, 68(2), 551-556.

Dorst, K., & Mandelkern, M. Good Guesses.

And finally: Can he do that?

Cartoon Credit: Poorly Drawn Lines, twitter: @PDLComics

Robert Talisse argues in Democracy and Moral Conflict that the epistemic justification for democratic conditions is also required to allow for moral pluralism because truth seeking is universal whereas the diversity values and moral commitments can preclude any way of resolving conflicts in a Rawlsian public reasons scenario. It seems like there may be some overlap with Democratic Reason.?