Ideas matter

Reasonable People #27: the middle ground between coincidence and necessity, why nudging isn't the same as framing, and persuasion strategy for those who believe in the power of ideas

Influence

The bible of research on persuasion is Cialdini’s (1984) Influence. Across 300 evidence-informed pages Cialdini sets out - with compelling examples and good humour - six principles of persuasion.

(Since this is the age of tl;dr I’m going to save you a click and put the six here: reciprocity, commitment and consistency, social proof, liking, authority and scarcity. Buy a suit because “sale ends Friday” - that’s scarcity. Buy the same suit everyone else is wearing - that’s social proof, and so on).

Cialdini’s portrayal isn’t just successful because he’s funny and well informed. All of us would like to know the cheat codes for human psychology - the full catalogue of the tricks, exploits and backdoors (but only for self-defence, right?). Influence is part of tradition of psychologists to fixate on quirks and foibles of human reasoning, the same tradition that leads directly to the Nudge / Choice Architecture account, whereby governments and other large institutions can sway people’s decisions by designing the way choices are presented.

You’d be a fool to claim there weren’t quirks and foibles in human psychology, but it is an equal mistake to act as if that’s all there is. Ideas matter, values matter, and arguments take on a life of their own (RP #9). Nudging may work, but the risk is that it narrows your conception of how the public can be related to.

Things Fell Apart

An illustration of how ideas have a life of their own can be found in Jon Ronson’s new radio series, Things Fell Apart. Here, Ronson tells “the origin stories of the culture wars” - tracing the history of celebrated (mostly US/internet) controversies.

The first episode, 1000 Dolls, tells the story of Francis Schaeffer a Christian theologian and art critic, co-founder of a Christian study community in Switzerland, L'Abri. I should tread carefully here because my knowledge of the 20th century history of the Christian right is minimal, but the way Ronson tells the story, Schaeffer is responsible for aligning US Evangelicals with anti-abortion activism - creating the modern pro-life movement. At the beginning of the 1970s anti-abortion activism was seen by many evangelical US Christians as a Catholic bug-bear, not an important issue for evangelicals. Schaeffer made a documentary and did a a tour of US, speaking to evangelical audiences, launching the issue as the central concern it is today.

Two coincidences drove this successful alignment. The first was that Schaeffer wasn’t initially minded to make abortion a central plank of his teaching. It was his son, himself a teenage father, who suggested Schaeffer include abortion in the documentary that launched his US fame. The whole documentary project itself, Ronson suggests, was prompted by Schaeffer’s desire to help with his son’s aspirations to be a film director. No son, no documentary; no teenage fatherhood, no request for inclusion of the topic of abortion. No documentary, no tour of the US. No tour, no modern pro-life movement.

The second coincidence was that Schaeffer’s tour was failing miserably, until the point it was boycotted by feminist activists. They’d got wind of the pro-life material and organised protests outside the venues. US Evangelicals were lukewarm about Schaeffer and particularly unresponsive to the material on abortion (again, as Ronson tells it), but one thing they knew for sure was that they hated feminists, so when they heard of the protests they threw organisational weight into getting attendance up on Schaeffer’s tour.

Even if partly true, this is an extraordinary picture of the role individual idiosyncrasies and historical accidents can play in ideological transformations. I had no idea that the evangelical movement wasn’t always 100% behind, and 100% fervent on anti-abortion policies. That this happened due to a weird combination of a son’s suggestion to his father and the coalition of Christian groups against a perceived common enemy underscores the sheer contingency at play. That things could have easily happened differently should make us humble.

An Aside about Alasdair MacIntyre

In Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, Alasdair MacIntyre (1988) accuses writers of intellectual history of two extremes. The one is to include the biography of the great thinkers as mere details, as if it is just incidental that Aristotle thought his thoughts in the Greece of the 4th century. The opposite extreme is to identify thinkers completely with the circumstances of their age, as if Aristotle’s thoughts were mere necessary expressions of the structural forces of society that were at play in Greece in the 4th century.

This same tension, between emphasising coincidence and emphasising necessity, holds for the Schaeffer story. Would the alignment between evangelicals and the pro-life movement have come about eventually, anyway? Or did the course of the world really turn on those small coincidences that Ronson describes?

MacIntyre gives us a resounding response. Balanced in-between cock-up and conspiracy is history, an account of the development of ideas which emphasises their contingent, chronological, development by communities of reasoners.

MacIntyre’s account is not only that history is a possible lens for understanding ideas, but that history -or more specifically, specific traditions - are the only lens:

Progress in rationality is achieved only from a point of view. And it is achieved when the adherents of the point of view succeed to some significant degree in elaborating ever more comprehensive and adequate statements of their positions through the dialectical procedure of advancing objections which identify incoherences, omissions, explanatory failures, and other types of flaw and limitation in earlier statements of them, of finding the strongest arguments available for supporting those objections, and then of attempting to restate the position so that it is no longer vulnerable to those specific objections and arguments. (p.144)

This historical account of rationality means that

There is no standing ground, no place of enquiry, no way to engage in the practice of advancing, evaluating, accepting, and rejecting reasoned argument apart from that which is provided by some particular tradition or other" (p.350)

Which leads MacIntyre to this rejection of liberalism and associated post-modern nihilisms:

…it is an illusion to suppose that there is some neutral standing ground, some locus for rationality as such, which can afford rational resources sufficient for enquiry independent of all traditions. Those who have maintained otherwise either have covertly been adopting the standpoint of a tradition and deceiving themselves and perhaps others into supposing that theirs was just such a neutral standing ground or else have simply been in error. The person outside all traditions lacks sufficient rational resources for enquiry and a fortiori for enquiry into what tradition is to be rationally preferred. He or she has no adequate relevant means of rational evaluation and hence can come to no well-grounded conclusion, including the conclusion that no tradition can vindicate itself against any other. To be outside all traditions is to be a stranger to enquiry; it is to be in a state of intellectual and moral destitution, a condition from which it is impossible to issue the relativist challenge. (p.367)

So, if I’ve read MacIntyre right, we must pay attention to the specifics of Schaeffer’s tour of the US, but these specifics represent not the play of mere chance, but of contingent events in the development of ideas. In MacIntyre’s account. ideas may have their own logic, their own momentum, and this logic is patterned by the specific history of the traditions within which they act. This doesn’t help us say what would have happened in an alternative reality where Schaeffer didn’t tour the US, but it does directly insist that we pay attention to the fact that he did, and because of these specific events, the tradition of US evangelicals evolved the way it did.

Frames

Another model for persuasion and influence is the ideas of frame and framing.

The idea is often maligned as adjacent to the something-for-nothing trickery of nudge. These shysters, accuse the critics, think they can fool the public by dressing up working for free as “exposure”, or presenting losing defined pension benefits as “retirement flexibility”. Framing, in this critique, is nothing but sophistry where you think you can sell something simply by altering the way it is presented, changing how you dress something up without altering its fundamental nature.

In, Don’t Think Of An Elephant: Know Your Values and Frame the Debate, George Lakoff gives an alternative account of framing. Framing, says Lakoff, is the art of connecting what you are saying right now to a value-laden understanding that your audience already holds. Good framing is supported by decades-long efforts to promote particular ways of thinking about the world, intellectual edifices which you can then invoke in a moment with a particular turn of phrase.

This, says Lakoff, is the work that US Conservatives have invested in, because they believe in ideas, while progressives have too often thought they could get away with letting the facts speak for themselves.

Lakoff’s account is tied to his work on the psychology of metaphor (so called, conceptual metaphor theory). Words evoke metaphorical schemas, and so your choice of words (the framing) lets you pack in associated concepts and conclusions to a simple phrase. So “tax relief” frames tax cuts within the scheme of relief - burdens which can and should be alleviated. Being “pro choice” frames abortion within the scheme of options, choice, freedom (and opponents as being anti-choice). And so on.

The point is not to start by dreaming up the most cunning framing to disguise what you want to do. The point is to develop the wider conversation - about minimal government (in the case of “tax relief”), about reproductive rights (in the case of “pro choice”) - the ideas and history of which you can then connect to with every use of the framing phrases.

Framing is not adjacent to nudging because framing takes ideas - and our status as reasoning, feeling, beings - seriously. Framing asks us to embrace the same middle ground. We can believe that it matters how something is presented, but also endorse that presentations are not arbitrary. Different frames are possible because of where we are coming from, because of the history of ideas that proceeded us.

Shit-posting our way into the future

There’s an interview with a Trump supporting internet activist from 2017. I heard it via the The Coming Storm documentary, but it was originally in an interview for This American Life. Jay Boone, the activist, says of Trump “We memed him into the presidency. We memed him into power. We shit-posted our way into the future.”

There’s a temptation, following the upset of 2016, to think that these events must be due to memes, or magic, or mind control of some kind. This is a mistake - in retrospect it was obvious that there was enough establishment resentment to make Trump’s election a real possibility.

But that doesn’t mean the memes are irrelevant. The memes mattered, because they gave expression to existing political animus. You couldn’t make good memes without the resentment. In their own way, the devilish shit-posters of the internet believe in ideas, even as they throw their backs against the erosion of all public discourse.

Held together

The motive of this newsletter, of Reasonable People, is to articulate the middle ground, the view of our psychology between being entirely biased and entirely rational. The middle ground position isn’t that we are half biased and half rational - instead it is something more like : our biases have rationale, and you can’t reduce reasoning to either logic (on one hand) or mere motivations (on the other).

There’s an analogous middle ground in trying to understand events. History is not just a series of coincidences, not entirely cock-ups, but it is not entirely conspiracy either. A series of coincidences that matter, maybe? Or perhaps, competing conspiracies of different levels of ineptness.

MacIntyre’s account is appealing to me because he is arguing that you have to start from somewhere to understand an argument, there’s no view from nowhere (or, rather, the view from nowhere abstracts so much it deprives you of the context you need to truly understand). Ideas have a history and life of their own, which we contribute to, but don’t completely control.

Putting too much faith in nudges, or memes, or mind-control, betrays the reality of our complex relation to ideas, our agency as reasoning, acting, individuals. Because individuals are drawn to follow the thread of ideas, to minimise outright contradiction, to pursue implications, ideas themselves have their own agency. Our story about why things happen and how things change must include both aspects, individual choices and the power of ideas. The ideas matter

* *

BBC/Jon Ronson: Things Fell Apart.

Cialdini, R.I. (1984). Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion (William Morrow & Company.

Lakoff, G. (2004). Don't think of an elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing. Here’s the short version

MacIntyre, A. (1988). Whose Justice? Which Rationality? Duckworth

Thaler, R. H. & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-14-311526-7.

(related)

Reasonable People #7: Barnacle Geese, Bright Lines and The Regulation of Beliefs

Reasonable People #9: Reason is no mere slave

Reasonable People #22 : Microtargeting is not mind control

If you enjoy the newsletter, please consider forwarding it, or telling people about it by sharing this link tomstafford.substack.com and if you can complete or complement any of my half thoughts, please hit reply and get in touch

Short notes and links follow…

Nudge policies are another name for coercion

Henry Farrell & Cosma Shalizi in New Scientist (2011):

This points to the key problem with “nudge” style paternalism: presuming that technocrats understand what ordinary people want better than the people themselves. There is no reason to think technocrats know better, especially since Thaler and Sunstein offer no means for ordinary people to comment on, let alone correct, the technocrats’ prescriptions. This leaves the technocrats with no systematic way of detecting their own errors, correcting them, or learning from them. And technocracy is bound to blunder, especially when it is not democratically accountable.

…libertarian paternalism treats people as consumers rather than citizens. It either fails to tell people why choices are set up in particular ways, or actively seeks to conceal the rationale.

By cutting dialogue and diversity for concealed and unaccountable decision-making, “nudge” politics attacks democracy’s core.

Farrell, H., & Shalizi, C. (2011). Nudge’policies are another name for coercion. New scientist, 2837, 28.

Nudges definitely maybe work

A recent meta-analysis from Mertens et al (2022) suggests that nudges are generally effective (“choice architecture interventions overall promote behavior change with a small to medium effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.45”).

But Szasci et al (2022) claim this is a misrepresentation. The Mertens report focusses on a headline figure which is the average strength of published studies. If unsuccessful studies are less likely to be published, this figure will be an overestimate. The Mertens paper itself even reports evidence of publication bias, and Szasci apply their own bias correction methods to give estimates of true, average, effect sizes which are much closer to zero.

A case in point is the note, from Mertens, that nudges show “a particularly strong effect on behavior in the food domain”. Their meta-analysis contains a number of studies from the Cornell lab of Brian Wansink, notorious for producing unreproducible research (Wansick has since resigned following upheld accusations of scientific misconduct).

If you include false figures in the average, how useful is the average? And how many of the constituent figures are false? We just don’t know, but many people would bet “a lot”. GIGO.

Additionally, the original meta-analysis highlights considerable variability in effects, and Szasci et al argue that we still don’t really understand where this variability comes from. If we don’t know that nudges generally work, or, if they do work, when they do, what do we really know?

Mertens, S., Herberz, M., Hahnel, U. J., & Brosch, T. (2022). The effectiveness of nudging: A meta-analysis of choice architecture interventions across behavioral domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(1).

- kudos to the authors for including Open Data so I could check the studies they included ones from Wansink

Szaszi, B., Higney, A., Charlton, A., Gelman, A., Ziano, I., Aczel, B., … Tipton, E. (2022, January 19). No reason to expect large and consistent effects of nudge interventions. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/mwhf3

pair with

Milkman, K. L., Gromet, D., Ho, H., Kay, J. S., Lee, T. W., Pandiloski, P., ... & Duckworth, A. L. (2021). Megastudies improve the impact of applied behavioural science. Nature, 600(7889), 478-483.

[In] a megastudy targeting physical exercise among 61,293 members of an American fitness chain, 30 scientists from 15 different US universities worked in small independent teams to design a total of 54 different four-week digital programmes (or interventions) encouraging exercise...Only 8% of interventions induced behaviour change that was significant and measurable after the four-week intervention....Forecasts by impartial judges failed to predict which interventions would be most effective

Persuasion strategy advice from Abraham Lincoln

A speech by Abraham Lincoln on February 22, 1842, aged 33, to the Springfield Washington Temperance Society. After some words about the successes of the Temperance movement, he moves to the reasons for this success (converts) and aspects of Temperance strategy which he views as less helpful:

Too much denunciation against dram sellers and dram drinkers was indulged in. This, I think, was both impolitic and unjust. It was impolitic, because, it is not much in the nature of man to be driven to anything; still less to be driven about that which is exclusively his own business; and least of all, where such driving is to be submitted to, at the expense of pecuniary interest, or burning appetite. When the dram-seller and drinker, were incessantly told, not in accents of entreaty and persuasion, diffidently addressed by erring man to an erring brother; but in the thundering tones of anathema and denunciation, with which the lordly Judge often groups together all the crimes of the felon's life, and thrusts them in his face just ere he passes sentence of death upon him, that they were the authors of all the vice and misery and crime in the land; that they were the manufacturers and material of all the thieves and robbers and murderers that infested the earth; that their houses were the workshops of the devil; and that their persons should be shunned by all the good and virtuous, as moral pestilences -- I say, when they were told all this, and in this way, it is not wonderful that they were slow, very slow, to acknowledge the truth of such denunciations, and to join the ranks of their denouncers in a hue and cry against themselves.

To have expected them to do otherwise than they did -- to have expected them not to meet denunciation with denunciation, crimination with crimination, and anathema with anathema, was to expect a reversal of human nature, which is God's decree, and never can be reversed. When the conduct of men is designed to be influenced, persuasion, kind, unassuming persuasion, should ever be adopted. It is an old and a true maxim, that a "drop of honey catches more flies than a gallon of gall." So with men. If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend. Therein is a drop of honey that catches his heart, which, say what he will, is the great highroad to his reason, and which, when once gained, you will find but little trouble in convincing his judgment of the justice of your cause, if indeed that cause really be a just one. On the contrary, assume to dictate to his judgment, or to command his action, or to mark him as one to be shunned and despised, and he will retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart; and though your cause be naked truth itself, transformed to the heaviest lance, harder than steel, and sharper than steel can be made, and though you throw it with more than Herculean force and precision, you shall be no more be able to pierce him, than to penetrate the hard shell of a tortoise with a rye straw.

Such is man, and so must he be understood by those who would lead him, even to his own best interest.

This is key: “assume to dictate to his judgment, or to command his action, or to mark him as one to be shunned and despised, and he will retreat within himself, close all the avenues to his head and his heart”. What is remarkable is not so much that Lincoln could diagnose this accurately in 1848, but that we still so routinely seem to fall back on the ‘thundering tones of anathema and denunciation’ strategy in 2022.

(This via A., thanks!)

Don't call people out -- call them in

Loretta J. Ross on an alternative to call out culture.

This also via A.

"calling in will be to this digital age human rights movement of the 21st century what nonviolence was to the civil rights movement in the 20th century"

Link on TED site (includes transcript)

And finally…

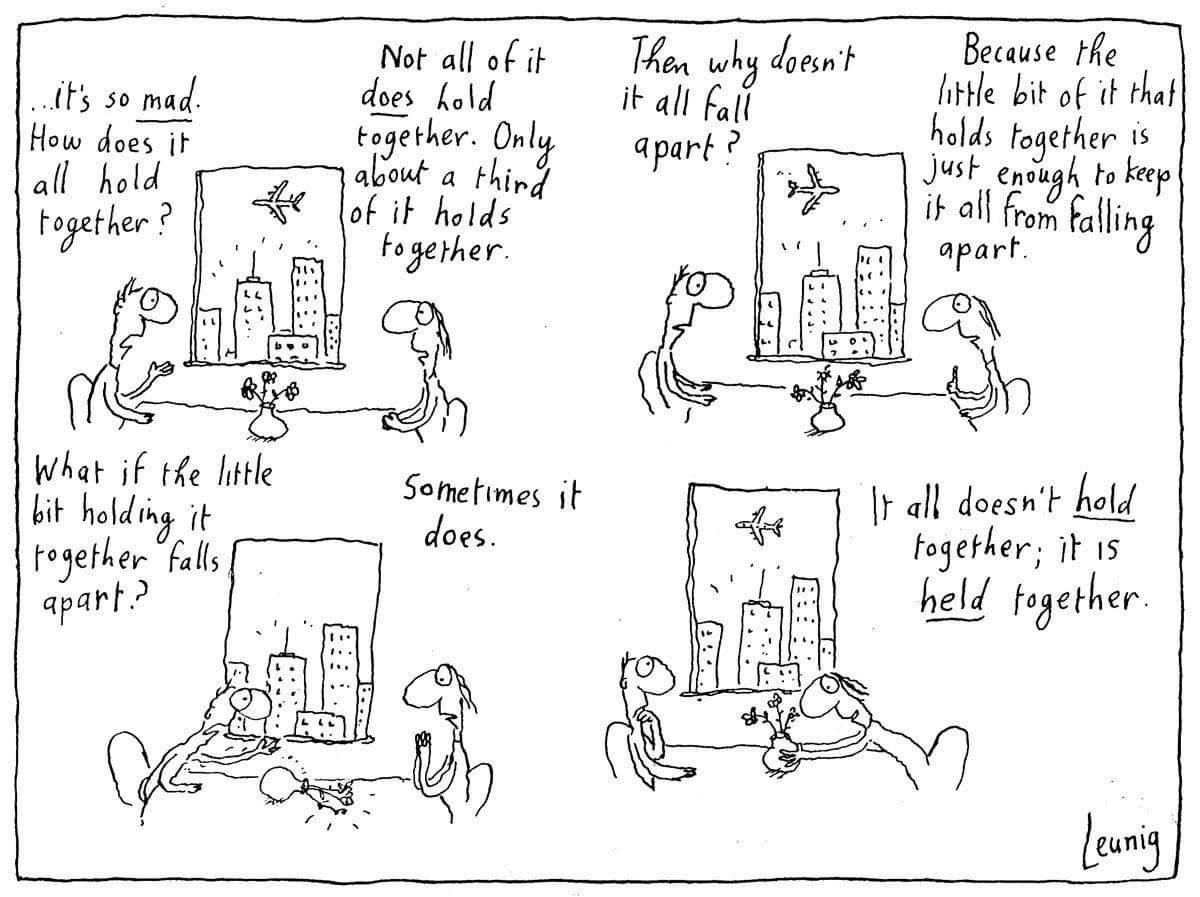

A statement of faith, the cartoonist Michael Leunig