Reason is no mere slave

Reasonable People #9: Review of Singer's "The Expanding Circle", a job opportunity working on online arguments with me, Kevin Dorst's new project, and bonus links

It’s a buffet this week folks. No main course, just tasty morsels from my recent reading.

Book: The Expanding Circle (1981), by Peter Singer

An extended reply from the ethical philosopher to E.O. Wilson’s Sociobiology. Wilson’s book sought to explicitly bring human behaviour within the scope of animal behaviour, and also said, it seems, that science would replace philosophy as arbiter of ethics. Singer disagrees.

Singer’s argument doesn’t involve denying the relevance of evolution. He places the origin of reasoning firmly within the history of our biological evolution, and the particular nature of reason as due to the conundrums of social life that are core to the evolutionary consideration of behaviour

Ethical reasoning, according to Singer, began as justification. Justification implies an audience, and that audience initially was the small group of our fellow ancestral humans. But, Singer argues, the very act of justification requires adopting a “disinterested stance”, and a disinterested stance is the trigger for a chain reaction. Once you start trying to put things within a framework which doesn’t depend on the particular individuals or circumstances involved, that disinterested stance has no natural limit. The initial audience for reasons may have been a small group, but soon the implicit audience of reason becomes increasingly abstracted in time and space; an expanding circle of ethical concern. First your family, then your tribe, then other tribes you have contact with. Then all of humanity. Then all sentient beings.

The capacity to reason is a special sort of capacity because it can lead us to places we did not expect to go. This distinguishes it from, say, the ability to type. As I work on the draft of this chapter, I am using both my capacity to reason and my ability to type. My ability to type produces the results I expect-that is, the words I choose to convey my thoughts appear on the paper in my typewriter, more or less as I wanted them to. My capacity to reason, on the other hand, has less predictable consequences. Sometimes an argument that appeared sound turns out to be fallacious. I may have to drop a position I formerly held, even abandon a project I find I cannot complete. Matters can also take a brighter turn: I may see a connection between two points that I had overlooked before. I may become persuaded of something that I did not previously believe. Beginning to reason is like stepping onto an escalator that leads upward and out of sight. Once we take the first step, the distance to be traveled is independent of our will and we cannot know in advance where we shall end. (p88).

Once reason has evolved it possesses an internal dynamic that makes it an independent entity. This does not mean reason is cut off from biological interests, just that it is not completely subservient. “Reason is no mere slave”, he says (p143), despite its evolution as tool of genes. “Tools have a way of influencing the purpose for which they are used” (p142).

He doesn’t use the language of complex systems, but what Singer is proposing has something of the flavour of a self-organising system about it. Evolution produces complexity; complexity finds the capacity to reason; reason is driven to reduce inconsistency and BOOM! Philosophy!

Once reason is established, the engine of its dynamic is a need for consistency (see RP#7). Singer recalls Festinger’s work on cognitive dissonance. Festinger said “the existence of nonfitting relations among cognitions…is a motivating factor in its own right”. That is, we have a drive to reduce feelings of inconsistency just as we have a drive to eat when we feel hungry.

His account of the inevitable victory of disinterested accounts is Whigish:

Reason is inherently expansionist. It seeks universal application. Unless crushed by countervailing forces, each new application will become part of the territory of reasoning bequested to future generations (p99)

Even if we grant all this, I’m more hesitant about the inevitability of the destination. Singer argues that all people, in all cultures, have happened upon the golden rule of “do unto others as you wish they would do unto you”, and that the next step will be to include non-human animals in the circle of our concern.

Maybe.

Consistency may be a common driver of reason, but you can get large variations in outcome from small variation sin in initial conditions. This is, I guess, what can lead sensible people to come to very different conclusions about topics: it doesn’t take much, just small changes in life experience, assumptions, or the weighting of various considerations to drive a self-organising system of reasons towards different stable states, internally consistent in themselves, but divergent from other conclusions.

Singer’s book is lucidly clear, an exciting demonstration of philosophy grounded in natural science accounts of human origins. You don’t have to accept his conclusions about the inevitability of the expanding circle of moral concern to be inspired by his account of the autonomy of reasoning. Yes, ideas have a force and life of their own, even when they are traded by limited, biological, selfish, humans.

We are reasonable people.

Cut from Goya’s El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (1799)

Job: Research Associate on “Engaging Dialogue Generated From Argument Maps”

If you have a PhD, or will do soon, and would like to work with me on a new project evaluating dialogues between humans and bots about controversial topics please click here. Here’s the project abstract.

The idea is to design a “dialogue system” interface to existing databases of the arguments surrounding controversial topics such as “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union?” or “Should all humans be vegan?”. In particular, a user can have a “Moral Maze” style chat with the dialogue system.

“Moral Maze” is a longrunning popular BBC 4 Radio programme in which a panel discusses a controversial topic with the help of witnesses and a host who chairs the conversation. The dialogue system consists of a panel of Argumentation Bots (ArguBots) who present arguments for or against the topic under discussion (the pro and con ArguBots), a host ArguBot and a witness ArguBot (that can provide detailed evidence). The user is invited to join the panel and voice their views on the topic under discussion. Thus the user can explore what they thought and what others thought about the controversial topic.

An important part of the projects will be to evaluate the effects on people’s appreciation of the complexity of debate and attendant ability to comprehend the world from other people’s point of view or perspective.

Due to start January 2021. No doubt I’ll have more to report once we’ve started. Please forward to anyone who might be interested. Informal enquiries welcome at any point.

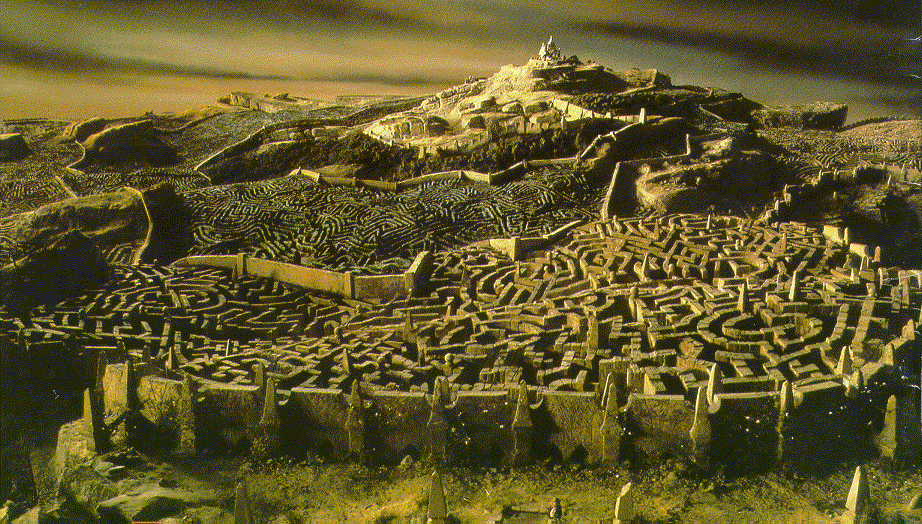

More of a moral labyrinth than a moral maze

Kevin Dorst: A Plea for Political Empathy

“Society is more polarised than ever”, is one of those things ‘everybody knows’, but Kevin Dorst makes the important point that in many domains polarisation per se isn’t a problem. The reason polarisation is problem is how our feelings have changed towards people who disagree with us :

This is new. Between 1994 and 2016 the percentage of Republicans who had a “very unfavorable” attitude toward Democrats rose from 21% to 58%, and the parallel rise for Democrats’ attitudes’ toward Republicans was from 17% to 55%:

So we do have a problem, and polarization is certainly part of it. But there is a case to be made that the crux of the problem is less that we disagree with each other, and more that we despise each other as a result.

In a slogan: The problem isn’t mere polarization—it’s demonization.

If this is right, it’s important. If mere polarization were the problem, then to address it the opposing sides would have to come to agree—and the prospects for that look dim. But if demonization is a large part of the problem, then to address it we don’t need to agree. Rather, what we need is to recover our political empathy: to be able to look at the othe

What feeds demonisation? The success of a particular brand of cognitive science, marked by the award of the Nobel prize to Kahnemann in 2001, which celebrates heuristics and biases in human judgement. The consequence:

we are now swimming in irrationalist explanations of political disagreement

Dorst’s project will be to undermine ‘irrationalist narratives’, defending human rationality and revisiting supposed evidence for irrationality and bias’. Needless to say I am completely on board with this!

Link: A Plea for Political Empathy - Dorst sets out his research programme.

Also: The Rational Question where he shows how you can reinterpret a couple of common biases (Hindsight bias and the sunk cost fallacy as rational).

Tom Stafford: Evidence for the rationalisation phenomenon is exaggerated

Yep, that me.

Fiery Cushman has published a long article in Behavioral Brain Sciences Rationalization is rational which presents the theory that post-hoc rationalisation of our actions might have a wider purpose, rather than just being an example of us not knowing the real reasons for why we act and, as a result, improvising. Cushman argues that rationalisation allows "representational exchange" between various sub-personal processes. I have written short commentary, which doesn’t disagree with the main thesis (which I think is interesting), but contests some of the motivating research. Studies on rationalisation suffer, like so much work in psychology, from an inflated need to emphasise our irrationality and bias. So, I say:

The evidence for rationalization, which motivates the target article, is exaggerated. Experimental evidence shows that rationalization effects are small, rather than gross and, I argue, largely silent on the pervasiveness and persistence of the phenomenon. At least some examples taken to show rationalization also have an interpretation compatible with deliberate, knowing, reason-responsiveness on the part of participants.

Mine is just one of many, more fascinating, commentaries, so I recommend the article and commentaries for a great example of scholarly debate on the topic

New Statesman: Why politicians and journalists should ban themselves from using Twitter.

Ian Leslie is fairly clear on the epistemic effects of twitter (see RP#8):

Twitter is the worst thing to ever happen to MPs, and therefore to politics, and therefore to us. …[it] makes politicians and journalists do their jobs differently: they commit to views more hastily, burn relationships and shun nuance.

New Yorker: Slow Ideas by Atul Gawande (July 2013)

Great piece about the diffusion of standards, norms and practices, and how sometimes the most inefficient method may be the only one that works: “People talking to people is still how the world’s standards change.”

Podcast: Michael Lewis’s Against The Rules

One of the kings of nonfiction has an eleven-part podcast series about the decline of referees in all domains of American life. Psychology people will definitely want to check out episode #3 The Alex Kogan Experience. Kogan was the academic who found himself at the heart of the Cambride Analytica scandal, having used privileged access to Facebook’s platform to harvest data and create tools which then ended up with the Trump campaign. The way Lewis tells it, the tale is really one of the failures of journalists and journalistic regulators who should have checked their story better - Kogan became a scapegoat for our need to find some easy explanation for Trump’s victory, and a story about a sinister spy-psychologist was easier to believe than that Democratic elites were complete blindsided by the reality of the life for many US voters.

I spoke to Alex Kogan briefly in 2014, after he gave a seminar reporting on his work predicting personality from facebook data, the work which was later to get him into so much trouble. There are two things I’d like to report. First, that - to my shame - no bells rang about the data security issues of harvesting data on people’s friends (just because this was technically possible doesn’t make it a good idea). Second, Kogan was infectiously enthusiastic about the science he was doing. It was clear he was excited about getting some cool data and using some cool techniques to test ideas about human psychology. Those are things I find exciting too. Probably this excitement was part of the reason I didn’t stop to question the data ethics of it all.

The rest, as they say, is history.

Review: of Eleanor Gordon Smith’s “Stop Being Reasonable” by Fleur Jongepier

She gives it five stars, and I agree.

…And finally

h/t @rogierK