Large Language Models and the Amazon-next-day-delivery trick

Understand this to see behind the curtain of AI's appearance of intelligence

You need to understand that large language models do not have a mind.

Although they use the human language. Although they can speak of all human things. Although you can have what seems like a human conversation with them, they are not minds, their outputs are not thinking.

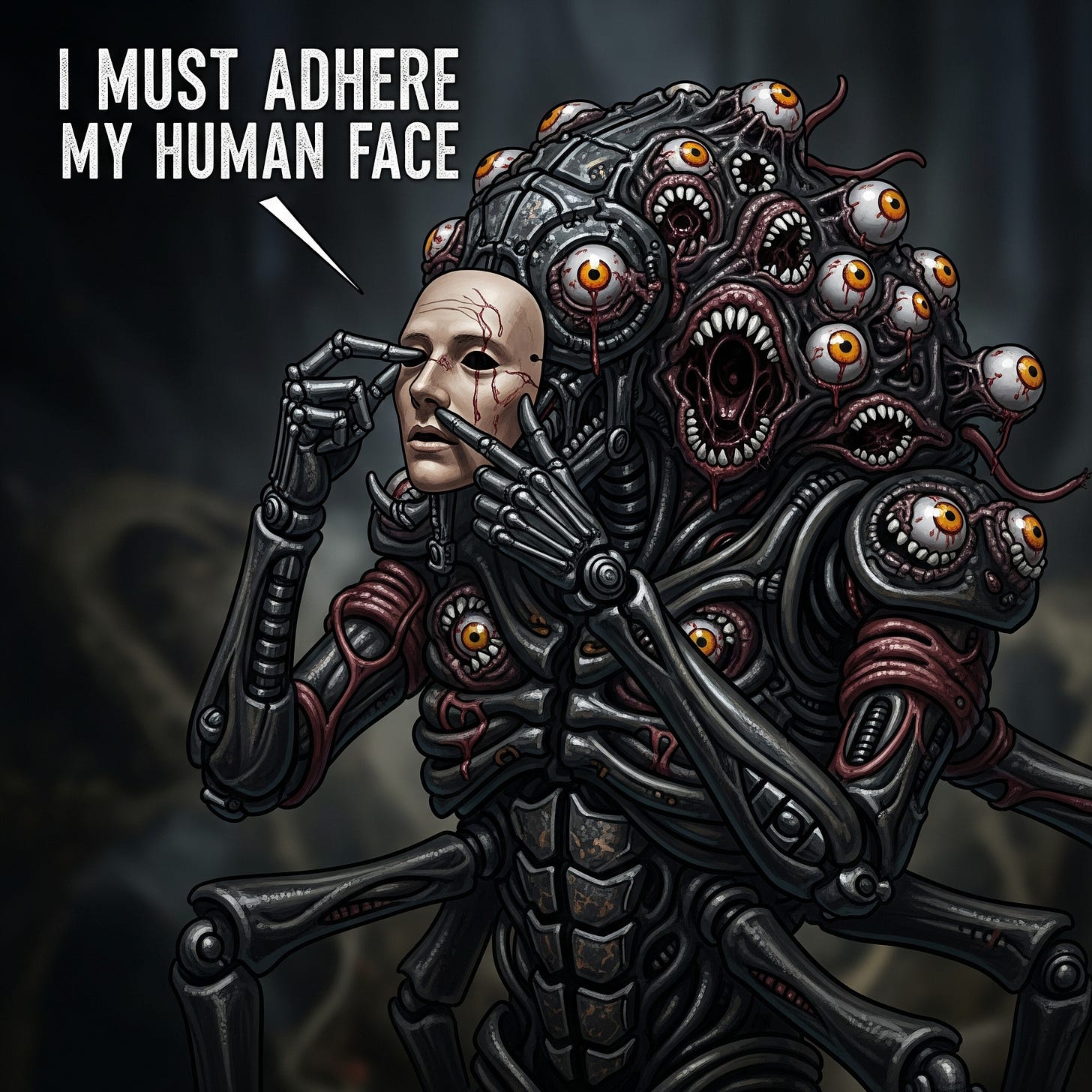

They wear our face but this is a trick.

Once you appreciate this, the surprising successes seem less miraculous, and the surprising failure more inevitable.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying that the AI of language models is a cheap trick - it is a very, very expensive trick. What the models can do is amazing, but they constantly try and seduce us into treating them like they are a person, and this is a dangerous misconception.

People have shame and so care about making stuff up, or at least getting caught out. Language models have no embarrassment; are happy to make plausible sentences without regard for the actuality, to project total confidence regardless of their actual knowledge. They are endlessly polite, infinitely patient, even sycophantic, in a way that would be deeply weird for any human.

This we know.

The consequence though, is that our normal metrics for trusting a human become unreliable. Confidence and fluency normally connote real knowledge (which is why bullshitters wreak such havoc), and knowledge is normally hard won, connoting intelligence and effort.

AI has the knowledge of a billion human hours of writing, and can use this to appear intelligent without actually possessing the intelligence (or humility, or focus) that a human expert would need to possess to obtain that knowledge.

Here’s a way to think about the way the language model trick works: Amazon next day delivery.

Amazon next day delivery seems magical. At 10pm I think “I need AAA batteries” or “I need a toothbrush”, or any of ten thousand things I can think of, and Amazon can delivers the next day.

The magic is in the feeling that Amazon can get anything and everything to me the next day, but the trick has very definitely limits.

What would truly be miraculous for my local corner shop is possible for Amazon because - like AI - it exists on a inhuman scale. Although I don’t know until 10pm that I might want batteries, or whatever, there is a fairly stable top 10,000 items that people order from Amazon, and Amazon can build a huge warehouse on the edge of town and put in it a thousand copies of each of the top 10,000 items.

Amazon’s magical ability to deliver the next day relies on scale and our own predictability. Crucially, the magic stops working as soon as you order something truly unusual.

Ask for the book Plant Galls (Collins New Naturalist Library, Book 117) or a miniature concrete model of Birmingham Central Library and the trick stops working. You have to wait a standard amount of time.

For AI, we get wowed when it can answer any question that pops into our head at 10pm at night. “How did Islam spread in China?”, “Why is the sky blue?”, “What’s the best way to defrost milk?” and so on for any of the ten thousand things, but we need to appreciate that most of our questions have been asked before, and the answers - produced by old-fashioned human intelligence - were captured and absorbed by the AI as part of the training data.

A human that knew the answers to all of these things would have dedicated a lifetime to studying. AI is just recycling these human hours of dedication. For the topics which haven’t been written about we shouldn’t expect it to to display native intelligence.

The shock of language models is exactly how much of human intelligence and experience has already been captured in written text. The models are great at adapting, recycling and summarising this knowledge, but that’s what they do. They are not minds, and we should not related to them as persons, any more than a book is a person.

If you enjoy the “AI as amazon next day delivery” concept, you may enjoy my last newsletter: AI will be the biro of thought. After the break, links on the normal topics of cognitive science, reasoning and persuasion.

Previously

(…on this newsletter)

My take from January 2023 when chatGPT seemed very new. We can check and see if what I said then holds up: Artificial reasoners as alien minds

Developing a measure of our faith in reason, new work from me: Belief in the reasonableness of others (January 2025)

Our piece in New Scientist bring evidence to worries about online manipulation: The truth about digital propaganda (September 2024)

Sheffield Tribune: The ‘harmful pseudo-science’ infecting Sheffield’s family courts

Story from my local describing the debunked theory of “parental alienation”, and how it allowed one expert to recommend that claims of abuse were in fact evidence of a lack of abuse. Here’s some of the expert testimony quoted in the article:

“[W]hile rejection of an abusive parent is considered to be an adaptive coping strategy where the child has been subject to abuse, such a response is highly unusual. Children have an innate, evolutionary drive to attach to their caregivers irrespective of the quality of care received, even where the caregiver is abusive. Most children who are abused by a parent struggle to disclose their abuse due to feelings of confusion and issues of loyalty and inner conflict. They usually resort to internalising coping mechanisms such as denial, silence and secrecy.”

Fans of the history of psychology will recognise the unfalsifiable dark pattern this projects on to the abused child: reporting abuse is evidence you are not being abused.

Link: https://www.sheffieldtribune.co.uk/the-harmful-pseudo-science-infecting-sheffields-family-courts/

When do politicians engage in discourse – and when do they avoid it?

A neat study of the German parliament 1990 - 2020 which looks at who tries to initiate discussion during debates, and who accepts these invitations for discussion. As well as the technically impressive steps in creating a dataset of “14,595 attempted and successful interventions (Zwischenfragen) – extraordinary, voluntary discursive exchanges between speakers and MPs in the audience – in the German Bundestag”, the study suggests that the increased divisiveness brought by the rise of MPs from the (far-right) AfD caused a rise in MPs refusing engagement - preferring to hold the floor, rather than engage in debate. Can we see in this an analogue of what happens in some corners of social media? Lack of common ground and/or polarisation encourages people to use their speaking power for status-seeking broadcast, rather than genuine discussion.

LSE Impact blog: When do politicians engage in discourse – and when do they avoid it?

Paper: Koch, E., & Kuepfer, A. (2025). The politics of seeking and avoiding discourse in parliament. European Journal of Political Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.70013

Indicator: AI bots join Community Notes

A community of AI bots. X announced on Tuesday that it would allow AI Note Writers into its crowdsourced moderation feature Community Notes. “Humans still in charge”, the company hastened to explain, in a classic case of protesting too much.

Link: https://indicator.media/p/briefing-ai-bots-join-community-notes-and-clothoff-whistleblower-speaks

Previously on Reasonable People: The Making of Community Notes

PODCAST: Showing Open-Mindedness with Mohamed Hussein

I recommend the whole series by Andy Luttrell, including this episode in which Dr Hussein discusses his research.

Link: https://opinionsciencepodcast.com/episode/receptiveness-is-complicated-with-mohamed-hussein/

PODCAST: Naomi Oreskes on 'Writing on Ignorance'

Again, I recommend the whole HPS Podcast series (“Conversations from History, Philosophy and Social Studies of Science”) but Naomi Oreskes is a great guest. She is the author of “Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming” (with Eric Conway) and as well as discussing ‘agnotology’ (the study of the social construction of ignorance) she has some nice advice on writing for nonspecialist audiences.

…And finally

"They were three months passing through the forest", illustration for Old French Fairy Tales (1920) by Virginia Frances Sterrett. Via @PublicDomainRev

END

Comments? Feedback? Ideas for what the 10,000 most common chatGPT questions are? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

Thank you, the next day delivery comparison neatly shows how scale affects perception. I’d also use a comparison to certain rough kinds of “crowdsourcing” of answers to questions; where the knowledge of many people is averaged out to produce a relatively well weighted response or sensible prediction. Most of us wouldn’t typically confuse such “wisdom of crowds” with a thinking agent yet even without the appearance of an agent we perceive the appearance of “”wisdom.” So the powerful appearance of human communicative traits adds another layer. Tom, sincerely thank you for continuing to provide a bright light on the web.

Great post.

IMHO LLMs (anti•intelligences) are a vipers nest influencing choices & herd responses. The Trusted News Initiative & the compliance by all the LLM controlled mass media ... ugh. They not only censored, they shaped perceptions, —almost everyone wants to moo or stampede with the herd. It's usually safer to evade predation, with the occassionsl risk of cliff vaulting to death.

In any event, enough doom & gloom, I'm going to enjoy breaking a 40 hour fast!

LLMs ≠ Human —

https://open.substack.com/pub/captainmanimalagonusnret/p/llms-human

https://open.substack.com/pub/captainmanimalagonusnret/p/llms-human-part-2