Microarguments and macrodecisions

Reasonable People #37: Warm up for discussion at the Site Gallery on tools, technology, craft and agency.

Two dominant dynamics in group decision making are herding and polarisation. In herding, members of a group all swing behind a single view, possibly the one held by the majority, or by the loudest, most convinced, members. With polarisation, opinion splits into two camps, which mutually repel, moving towards the extremes and/or drawing in those who might otherwise hold more intermediate views.

Herding and polarisation are easy to diagnose - you just need to know where everyone stands. It the sort of thing you can pick up in a simple survey item - “How much to you agree with the following statements, on a scale of 1 (Totally Disagree) to 7 (Totally Agree)”. You can also model herding and polarisation relatively easily, you just assume everyone knows their opinion (on a 1 to 7 scale) and is willing to modify it slightly based on what they learn about everyone else’s opinion. If everyone hears everyone else and/or isn’t restrained in how much they are willing to shift you get herding as the whole network converges on some opinion. If there’s structure in who listens to who, and how, or how much some individuals are willing to shift you can get polarisation.

So it isn’t a surprise that these two dynamics also dominate how we talk about group decision making, and you wouldn’t be an honest observer of things like national politics or social media controversies if you denied that these dynamics do frequently play out, often simultaneously, with opinion herding within social groups or political parties, and polarisation between them.

There is another way of looking at group decision making, one that attempts to hold in view what is happening beneath the general level of description in which people’s view is summarised as a single point on a simple scale. This is the level of argument and discussion, the exchange of reasons as a vital part of the process by which a group makes decisions. The collective outcome is an emergent product of individual reasoners, and an environment of reasons, which they each individual both feeds into and feeds from.

This level description is the preoccupation of this newsletter, but I hadn’t recognised the connection to complexity theory until last week, when I was met the artist Jan Hopkins, as preparation for an evening of talks and discussion at Sheffield’s Site Gallery on 2nd of Feb: INTERFACE: Art/Technology/Collaboration. This will feature Jan, textile artist Seiko Kinoshita, live coder and pattern researcher Alex McLean, myself and Shuhei Miyashita of the University of Sheffield’s microrobotics lab. In-person event registration is here (free!).

What I learnt about Jan’s work was a deep preoccupation with technology and the nature of tools and collaboration. Listening to Jan and the other artists present talk, I got a vision of craft which was about using tools as generative devices, not merely instruments of control to enact a predetermined vision. Maybe this is easier to understand with traditional crafts like woodwork, where you can’t impose any idea on any piece of wood, but have to understand the grain of material, find out the possibilities as you work. This can be true of digital tools too - there’s a space of possibilities which are beyond what was imagined when the tools are made, even in the imaginations of their inventors.

I’m the wrong person to talk about the process of art and technology - you might have to come to the discussion on 2nd of Feb to get to the bottom of this - but I saw, for a moment, a connection to reasoning and how we think about what happens when we reason together.

Complexity theory is concerned with how simpler parts interact to generate interesting collective outcomes. A core concept is the idea of emergence, that patterns at some more general or abstract level can be understood by studying the properties of units at some closer, more specific or more granular level of description. Starling murmurations can only be understood by recognising how individual Starlings respond to each other, for example - there’s no blueprint or master controller for the swirling patterns they weave in the sunset sky.

The herding/polarisation view of groups is flattening - it reduces both the scope of possibilities to a single dimension and the people in the group so nothing more than possessors of opinions which fall as single points on that dimension. The study of argumentation asks us to hold in view the microprocesses which contribute to collective behaviour - the production, exchange, reception and iteration of reasons within and between individuals. Complexity theory demonstrates numerous systems where the outcome is no mere tranlation of the inputs, but a truly generative, autonomous, creation of the whole interacting system.

Genuinely engaging in argument means giving up a bit of control. Just as an artist has to listen to her tools and respect the agency of the material, arguers need to listen to each other and respect the implications of the system of reasons they are co-creating. This means giving up the idea that one fully controls the outcome - the conclusions emerge from the discussion, they aren’t preformed in the mind of any single participant.

It is this generativity of discussion which allows groups to outperform, in the right circumstances, the ability of any single participant. This is the reason I’m sceptical of any account which flattens participants in a discussion to a single descriptor, and of tools which collapse structure or context from arguments (as arguably short-form social media does). Good discussions, and good accounts of the nature of discussions, require we recognising structure and diversity in the space of reasons.

I’m looking forward to discussion of all these themes, as well as finding out more about Jan and Seiko’s art practice at the event on the 2nd of Feb. Please join us.

Event link: Site Gallery on 2nd of Feb: INTERFACE: Art/Technology/Collaboration. (in person) Event registration

(This won’t be streamed or recorded, so if you’re not in Sheffield, watch this newsletter for a post-event report.)

Further reading

Schelling, T. C. (1978). Micromotives and macrobehavior.

RADIO: BBC Outlook How the kindness of strangers stopped my terror attack

US Marine Mac McKinney returned from decades of war to his home town of Muncie, Indiana. Traumatised, with hate in his heart for all Muslims, he planned to bomb his local Islamic Centre. An argument with is young daughter led him to visit the Centre so he could gather evidence of the Muslim conspiracy against America. Contra his expectations, the loving kindness he experienced there completely reversed his opinion of Islam, leading him - a mere eight weeks later - to convert.

Most conversions aren’t such dramatic reversals, and aren’t so sudden, testament to both the extent of the crisis Mac was in the middle of, his own strength of character to change his mind, and the compassion and wisdom of the community that he planned such evil against and which - unbeknowingly - welcomed him into their community at the exact point of his, and their, greatest danger.

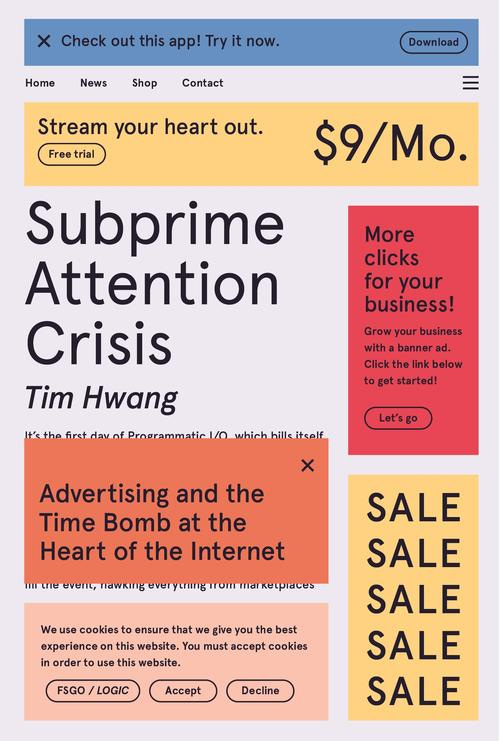

BOOK: Subprime Attention Crisis: Advertising and the Time bomb at the Heart of the Internet (2020) by Tim Hwang

The thesis is that online advertising suffers from the same misalignment of incentives, failures of regulation and opacity that created the financial crash of 2008. More, that the mechanisms of online advertising - algorithmic brokerage, increasingly complex derivatives - are directly inspired by finance. It is inherently difficult to discern the effects of advertising - even online advertising. Hwang reviews research which suggests that the classic quip (“I know half my advertising budget is wasted, but I don’t know which half”) is dramatically optimistic. Online advertising threatened a new era of targetted, effective advertising, but there is no good evidence this has materialised. The resulting bubble is a systemic vulnerability we should all worry about, argues Hwang. The bubble bursting would mean the billions spent on advertising - which indirectly fuels everything from machine learning research by DeepMind to humanitarian efforts by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative - would vanish from the industry. Love it or hate it, this would also mean the free services we’ve come to enjoy (facebook, google search, google scholar, unpaywalled news, etc) would be under threat. Hwang wants us to rethink the infrastructure of the internet, away from the advertising supported model, before it is too late (let’s have “a manageable crisis”, in his phrase).

Advertising is the original sin of the internet. Other online worlds are possible, even desirable. With this I’m on board.

Where I am less convinced by Hwang is that there is any mechanism of sudden collapse in the advertising bubble. With subprime mortgages, if people start defaulting on their payments it becomes clear that the assets are overvalued. The mechanisms of the financial market contain positive feedback loops which accelerates everyone finding this out at once. Does the advertising industry have such a mechanism? I don’t think so. It would take some new innovation (a demonstrably more effective advertising method? A step change in regulatory requirements around disclosure? A gold-standard RCT showing the ineffectiveness of online advertising?) for this to happen.

Lingis on the origin of reasoning

The will to give a reason characterizes a certain discursive practice. In the mercantile port cities of Greece, strangers arrive who ask the Greeks, Why do you do as you do? In all societies where groups of humans elaborate their distinctness, the answer was and is, Because our fathers have taught us to do so, because our gods have decreed that it be so. Something new begins when the Greeks begin to give a reason that the stranger, who does not have these fathers and these gods, can accept, a reason that any lucid mind can accept. Such speech acts are pledges. The one who so answers commits himself to his statement, commits himself to supply a reason and a reason for the reason; he makes himself responsible for his statement. He commits himself to answer for what he says to every contestation. He accepts every stranger as his judge.

Alphonso Lingis (1994). The Community of Those Who Have Nothing in Common (essays), p3 "The other community"

Would I recommend this book? I’m not sure, but there are some luminous moments.

PODCAST: Group psychology, polarization, and persuasion, with Matthew Hornsey

My favourite kind of podcast, like listening in on an intelligent discussion, with all the benefits that you don’t have to speak and so risk embarrassing yourself.

Summary

Topics discussed in our talk include: why people can believe such different (and sometimes such unreasonable) ideas; persuasive tactics for changing minds; tactics for reducing us-vs-them animosity; why groups mainly listen to in-group members and ignore the same ideas from out-group members; the effects of the modern world on polarization; social media effects, and more.

Contains these two quotes (roughly transcribed by me) from Hornsey:

People are not listening to what you say, they are listening to what they think you mean

Which I take to mean, you need to meet people where they are, not just transmit information, if you want to have a hope of persuading them. And

Credential your motives, not your arguments

By which he means that the largest factor in persuasion is people not trusting you, rather than the internal coherence of what you are trying to say

Lots of food for thought

From Zach Elwood’s People Who Read People: A Behavior and Psychology Podcast

Follow up’s on chatGPT

Last time I wrote about how chatGPT reasons (RP#36):

Here are a few follow-ons for thoughts in that newsletter.

I wrote about how one way to think about chatGPT is as a cognitive augmentation technology. I should have referenced this Carter & Nielsen’s 2017 essay Using Artificial Intelligence to Augment Human Intelligence

@svpino has some great - and specific - examples of how chatGPT can already be used in coding , illustrating exactly this - LLM as a force-multiplier on human intelligence

Counterpoint, as I illustrated, chatGPT is addicted to generating plausible answers without caring about accuracy even with maths

And finally, the always readable Dan Hon, has a suggestion for how to turn chatGPT’s addiction to bullshit into a virtue rather than a vice.

I’m pretty sure he’s just kidding

Hi Tom, I'm so pleased to have made it to this before publishing a somewhat epic length exploration of polarisation, reason and self-awareness. I'll be recommending it as one of the helpful tributaries for readers to navigate. Love so much in this thoughtful piece.