Quantifying our Faith in reason

Reasonable People #30: Measuring the core belief that people do what they do for good reasons.

The lost wallet

A slow day at the museum, and the receptionist is sitting at their desk as a stranger approaches, perhaps a tourist.

‘Hi’, the stranger begins, ‘I found this on the street just around the corner.’ He puts a wallet on the desk and pushes it over to the receptionist. ‘Somebody must have lost it. I’m in a hurry and have to go. Can you please take care of it?’. Without waiting for a response, the stranger turns and leaves.

The wallet is a clear plastic envelope, which the receptionist picks up and turns over. Inside they can clearly see a key, a shopping list, some business cards and a couple of bank notes.

A team of researchers travel the world, dropping wallets in this precisely scripted manner. They leave them at galleries and museums, banks, post offices, police stations and hotels. They travel the world, handing in lost wallets. Once they’ve left the wallet they leave immediately, noting whether the receptionist has a computer on their desk, whether there were colleagues watching, if there are security cameras in the building.

In India, flooding forces them to drop Chennai from their schedule. In Malindi, Kenya, they can’t drop any wallets because the research assistant is arrested and interrogated by the military police for suspicious activity. But in the end, after 3 years, they’ve dropped 17,303 wallets in 330 cities across 40 countries.

Back at his lab at the University of Michigan, Alain Cohn has a specially configured email server. Cohn and his research team wait. The business cards in each wallet have a fake name, and each one has a unique fake email address. The server logs the time between a wallet being dropped and somebody getting in contact to try to return the wallet.

What does the receptionist do with the lost wallet? What would you do? Nobody knows the wallet has been left where you work. Maybe nobody saw it being handed to you specifically. Can you be bothered to help return it to the owner? What about money? Would that make a difference? Perhaps you might decide to just… keep it?

Cohn and his team’s research project was a massive effort to find out the answers to these questions. What would people do, how did the money affect people’s choices, and how did this vary around the world? The answers say something about human nature, and about how our beliefs about human nature matter.

For me, the most interesting finding is not whether most wallets were returned (they were), or whether the wallets with more money in were more likely to be returned (also true), but the differences around the world in the rates at which the wallets were returned. These differences were huge, varying from 4 out of every 5 wallets being returned (in Scandinavia, of course, and Switzerland), to fewer than 1 in 5 being returned (in places including China, Peru and Kazakhstan).

Trying to understand this range led Cohn and his team to the World Values Survey, an international research effort that polls citizens around the globe about their beliefs and attitudes. One question, in particular, asks about faith in other people: ‘Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?’. In Sweden, for example, most people agree with this statement. In Peru, fewer than 10 per cent do. Cohn’s analysis suggests that it is this generalised trust in other people that drives the cross-cultural differences seen with the lost wallets.

* * *

Generalised interpersonal trust

The question Cohn looked at, the item in the World Values Survey, is a doubled ended statement: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”. Participants are either asked which they agree with, or shown just the first part (“Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted”) and asked to rate agreement. The question has been in something called the General Social Survey since the 70s. It is of discussed as a measure of ‘generalised interpersonal trust’ or simply ‘social capital’ (Brehm & Rahn, 1997) - a measure of our faith in our fellow citizens.

It is so standard that it has been asked all over the world, for many decades, so you can make maps like this:

This generalised trust in others seems important, but I’ve been thinking about how other beliefs feed into this belief. Why do we trust others? Do we trust them intellectually as well as morally? Do we think other people are able to work things out for themselves, to display good judgement? Do we trust the typical person to avoid being manipulated, to respond to arguments, to reason their way to good enough decisions?

It seems plausible that perceiving most people as irrational or misinformed is a crucial part of our feelings that most people cannot be trusted, while perceiving most people as reasonable could be a crucial part of feelings that most people can be trusted. This faith in reason could be a core belief, the kind of thing that has knock on effects for how you think about everything from democracy to calorie guidelines on food labels.

* * *

Measuring beliefs about human nature

Beliefs in human reasonableness seem so important that I assumed somebody, somewhere, would have invented a scale for measuring this faith in human reason. I’ve looked and I can’t find anything. This is a surprise, the engine of academic psychology turns by psychologists minting new concepts and new measures, putting the old wine of how punters respond to random questions into the new bottles of frameworks, theories and schema.

Here’s a few related-but-not-quite-it scales.

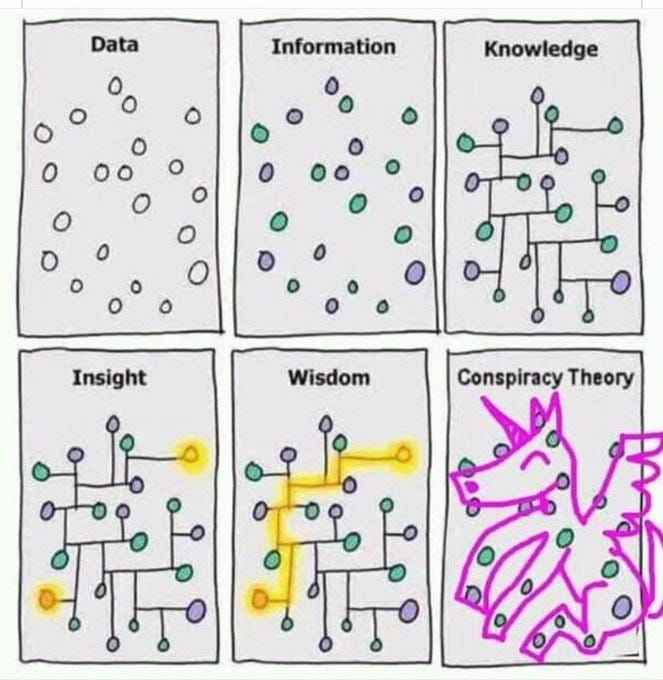

Conspiracy Thinking

Conspiracy Thinking scales (RP#29), like the Generic Conspiracist Beliefs scale which asks agreement with the statement “Groups of scientists manipulate, fabricate, or suppress evidences in order to deceive the public” or the Conspiracy Mentality Scale which asks agreement with “Some things that everyone accepts as true are in fact hoaxes created by people in power.” If the public has been deceived the implication is that we are more easily fooled, right?

Cynical beliefs about human nature

Some researchers have looked at what they call ‘Cynical beliefs about human nature’ (e.g. Stavrova & Ehlebracht, 2016; as discussed as discussed in RP#17), but when you drill down the work relies on generalised trust/distrust measures, the scale items do not touch on reason or rationality as a cause of cynicism.

Beliefs about human nature

Other studies which have looked at beliefs about human nature (e.g. Furnham, Johnson & Rawles, 1985), as far as I can tell, have questions which focus on the role of biology, genetics and/or heredity on psychological traits. For, for example, asking if participants believe personality is entirely caused by a person’s genetics.

The ‘Third Person Effect’

The third Person Effect (Davidson, 1983) is that others are more likely to be influenced or manipulated than you. So, if you ask people ‘How much would the exposure to fake news affect you’ or ‘how influential are online political ads on you?’ you get one set of answers, and if you ask about the effect on general voters you get another answer, one which indicates greater influence. Very often Third-Person Effect studies seem to ask about you vs an outgroup (e.g. people of the opposition political party), but some ask about you vs the general voters or typical person. The larger the social distrance (and more negative the influence) the stronger the effect.

This is definitely part of what I’m interested in - vulnerability to manipulation -, but the third person effect literature doesn’t ask about the positive aspects of rationality, or specifically about the role of good or bad reasons in people’s actions.

The missing scale

No study I can find seems to measure the wider beliefs that the typical person is reasonable, responds appropriately to reasons, or is capable of resisting manipulation. Maybe I missed a whole research area out of my own ignorance or ham-fisted use of search keywords. If you know of a measure that researchers or pollsters have deployed, please let me know.

In his 2019 essay, ‘On Digital Disinformation and Democratic Myths’, David Karpf warns that the real risks of digitial disinformation may be second order effects. Not that the public is misinformed (supported by research which shows that most people don’t see much fake news, and when they see it they aren’t likely to believe it), a first order effect. Rather, the second order effect may be that people come to believe that others are so distracted or deceived by fake news that politicians will no longer be held to account. If too many people come to believe this is true, politicans may, also, come to believe that they will no longer be held to account if they lie or are inconsistent. Chaos ensues! Karpf calls the idea of an attentive, informed public ‘a load bearing myth of democracy’ (discussed in RP#14). This idea is important not because it is 100% true, but because our belief in it helps regulate our behaviour as political actors.

This idea of a well informed, attentive, public is one of the things I would hope to measure if I had a set of good questions for measuring our faith in reason. Another thing, arising in our own work on perceptions of online political advertising: I have a hunch that these broader perceptions of public rationality will predict more specific beliefs about how tightly the government should regulate political advertising.

Fine, I’ll do it myself

So, dear reader, I’ve been thinking of making my own scale to measure perceptions of public rationality. There is a deep science of creating and validitating scales (Boateng et al, 2018, Clark & Watson, 2019). There’s a strong argument that psychologists in particular have too casual an attiude to just making up new measurements, without caring enough about the reliability, transparency and validity of the measures (Flake & Fried, 2020).

So, with those warnings, if I was going to do this I’d want to do it properly, and this post is by way of thinking aloud about a first steps. A way of trying to work out if this is a good idea (if you have intuitions about that let me know).

What elements would this scale have? One way would be to measure the positive and negative aspects of reasonableness. For the negative aspects we can ask if the typical person is:

irrational?

misinformed?

easily manipulated?

caused to act by reasons they don’t understand or endorse?

And for positive aspects, do they?

respond to good reasons, ignore bad reasons?

believe true facts about the world, not believe falsities?

have beliefs which don’t contradict each other?

behave consistently with their beliefs?

The positive aspects reflect, in order, reasonable skepticism (the ability to discriminate signal from noise), the correspondance criteria of rationality (having beliefs which reflect the true state of the world, and two flavours of a coherance criteria of rationality (having beliefs consistent with each other, and behaviours consistent with beliefs).

When I have some candidate questions, the next thing would be to trial them, and look at if responses on these measures predicted the kind of thing you would expect. I am open to suggestions for what these might be, but off the top of my head these might be: attitude to democracy, support for censorship/regulation of news and social media, and, of course, generalised trust. Since, if you don’t belief the typical person is reasonable, how could you trust them?

References

Boateng, G. O., Neilands, T. B., Frongillo, E. A., Melgar-Quiñonez, H. R., & Young, S. L. (2018). Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Frontiers in public health, 6, 149.

Brehm, J., & Rahn, W. (1997). Individual-level evidence for the causes and consequences of social capital. American journal of political science, 999-1023.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (2019). Constructing validity: New developments in creating objective measuring instruments. Psychological Assessment, 31(12), 1412–1427. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000626

Cohn, A., Maréchal, M. A., Tannenbaum, D., & Zünd, C. L. (2019). Civic honesty around the globe. Science, 365(6448), 70-73.

Flake, J. K., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Measurement schmeasurement: Questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 3(4), 456-465.

Davison, W. P. (1983). The third-person effect in communication. Public opinion quarterly, 47(1), 1-15.

Furnham, A., Johnson, C., & Rawles, R. (1985). The determinants of beliefs in human nature. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(6), 675-684.

Philpot, R., Liebst, L. S., Levine, M., Bernasco, W., & Lindegaard, M. R. (2020). Would I be helped? Cross-national CCTV footage shows that intervention is the norm in public conflicts. American Psychologist, 75(1), 66.

Stavrova, O., & Ehlebracht, D. (2016). Cynical beliefs about human nature and income: Longitudinal and cross-cultural analyses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(1), 116–132. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000050

More on conspiracy theories

Following the last newletter (RP#29, Conspiracy Thinking), I spotted a few nice titbits about conspiracy theories. (Coincidence?)

This cartoon, via Jay Van Bavel.

Image credit is unclear

This typically pithy thought from Cory,

“conspiracy is a rejection of the establishment systems for determining the truth” gets you a long way in my opinion.

And this paper from colleague Richard Bentall:

Three studies looked at the traits associated with conspiracist beliefs and “suggest[ed] that paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories are distinct but correlated belief systems with both common and specific psychological components”. People who were more paranoid were likely to have low self-esteem, while people who endorsed conspiracy beliefs were more likely to have high self-esteem, narcissisit traits and poor analytic skills (unskilled an unaware of it?)

Abstract: Paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories both involve suspiciousness about the intentions of others but have rarely been studied together. In three studies, one with a mainly student sample (N = 496) and two with more representative UK population samples (N = 1,519, N = 638) we compared single and two-factor models of paranoia and conspiracy theories as well as associations between both belief systems and other psychological constructs. A model with two correlated factors was the best fit in all studies. Both belief systems were associated with poor locus of control (belief in powerful others and chance) and loneliness. Paranoid beliefs were specifically associated with negative self-esteem and, in two studies, insecure attachment; conspiracy theories were associated with positive self-esteem in the two larger studies and narcissistic personality traits in the final study. Conspiracist thinking but not paranoia was associated with poor performance on the Cognitive Reflection Task (poor analytical thinking). The findings suggest that paranoia and belief in conspiracy theories are distinct but correlated belief systems with both common and specific psychological components.

Alsuhibani, A., Shevlin, M., Freeman, D., Sheaves, B., & Bentall, R. P. (2022). Why conspiracy theorists are not always paranoid: Conspiracy theories and paranoia form separate factors with distinct psychological predictors. PloS one, 17(4), e0259053.

And finally …

A Banx cartoon for everyone involved in research : “Institute of Umbilical Studies”.

Being reasonable is about much more than using reason; it also implies things as fairness and compromise. It’s a social skill. Arguably it is sometimes in tension with abstract reason.

Being reasonable does require the use of reason, but you miss a few key points in some of your suggested questions trying to determine if someone is reasonable. A reasonable person thinks using proper logic to derive proper conclusions from a set of premises. It also includes the ability to differentiate between coincidental relationships and causal relationships, an ability that is waning, I think.