Elliot had a very particular form of brain damage.

A brain tumour left him unable to feel emotion. His story is told in Antonio Damasio's "Descartes' Error" (1994).

He wasn't upset by his brain injury, nor pleased by his recovery. He would describe a near death experience with the same equanimity as he would discuss the weather. He wasn't upset by anything. His life was an emotional flatline.

Damasio tells Elliot's story to illustrate the role emotion plays in our decision making. Elliot had everything to support good decisions that a traditional account of reason requires: his perception, memory, language, IQ and general knowledge were unaffected. If anything, his Spock-like detachment from passion should make him a better decision maker, right?

Wrong.

Elliot's decision making was disastrously impaired, losing him both his job and his marriage. Damasio describes his difficulties at work:

"Imagine a task involving reading and classifying documents of a given client. Elliot would read and fully understand the significance of the material, and he certainly knew how to sort out the documents according to the similarity or disparity of their content. The problem was that he was likely, all of a sudden, to turn from the sorting task he had initiated to reading one of those papers, carefully and intelligently, and to spend an entire day doing so. Or he might spend a whole afternoon deliberating on which principle of categorization should be applied: Should it be date, size of document, pertinence to the case, or another?" (p36)

Damasio describes these problems in terms of framing:

"The flow of work was stopped. One might say that the particular step of the task at which Elliot balked was actually being carried out too well, and at the expense of the overall purpose. One might say that Elliot had be come irrational concerning the larger frame of behavior, which pertained to his main priority, while within the smaller frames of behavior, which pertained to subsidiary tasks, his actions were un necessarily detailed." (p36)

But it puts me in mind of Simon's notion of bounded rationality (see Reasonable People #2. Every decision is composed of sub-decisions; every possible choice could potentially overturn the impact of all other choices. Without arbitrary limits (a frame) reasoning can grind on endlessly without ever reaching a final decision.

The behaviour of another of Damasio's emotion-impaired patients illustrates this, as the doctor reports:

"I was discussing ... when his next visit to the laboratory should take place. I suggested two alternative dates, both in the coming month and just a few days apart from each other. The patient pulled out his appointment book and began consulting the calendar. The behavior that ensued, which was witnessed by several investigators, was remarkable. For the better part of a half-hour, the patient enumerated reasons for and against each of the two dates: previous engagements, proximity to other engagements, possible meteorological conditions, virtually anything that one could reasonably think about concerning a simple date. ... a tiresome cost-benefit analysis, an endless outlining and fruitless comparison of options and possible consequences. It took enormous discipline to listen to all of this without pounding on the table and telling him to stop" (p193)

The stories of these patients are used by Damasio to support his account of emotion in decision making. Descartes' Error, according to Damasio, was to separate "pure rationality" from bodily experience. Our bodies are the representational ground for a vital part of reasoning, and one which helps us escape the endless hall of mirrors of unframed, unbounded rationality. That vital part of reasoning is emotion. Emotions help us prioritise: focusing on the bigger picture, cutting short dead-ends, committing to previously settled considerations, biasing us away from risks, breaking deadlocks. Emotions, Damasio says, consistently inform all decision making via "somatic markers", bodily sensations which inform the decision process as a whole. The patients he saw suffered from brain injuries which cut off their access to these somatic markers, paralysing their decision making despite the rest of their cognitive machinery still working.

The traditional story contrasts emotion to reason, rather than placing it at the heart of reasoning, so it is interesting to rehearse the objections to the dichotomy.

There is a very abstract objection that, just theoretically, you need emotions to have a reason to do anything. Pure reason would lack any motivation pursue any goal, or values to support preferring one outcome over another. Hence the need for emotion (the very root of the word supports this idea - from the Latin emovere - to move out, remove, agitate). In "The Mind Is Flat" Nick Chater puts it well "having an emotion is a paradigmatic act of interpretation, and hence of reasoning" (2018, p99)

Aligned with this theoretical objections is Damasio's account - the empirical demonstrations that a relatively pure impairment of emotion can have catastrophic impact on reasoning.

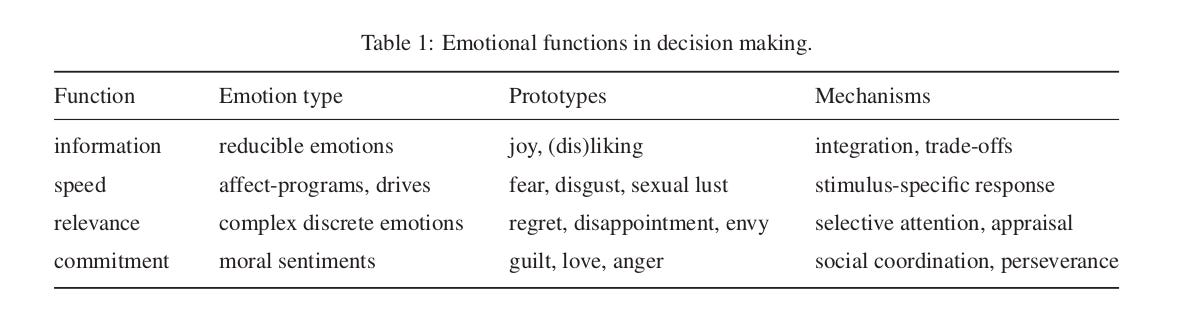

Reading Lisa Bortolotti's "Irrationality", I came across Pfister & Bohm's (2008) taxonomy which proposes that emotions actually play four distinct functions in impacting reasoning:

Information: Inform preferences by providing information on pleasure and pain

Speed: Drive rapid choices under time pressure

Relevance: selective attention to relevant information

Commitment: force sticking to decisions once made

We could argue about their account, but I think it is nice in that it breaks down both the roles emotion can play, but also highlights the specific emotions which might play these different roles, and the cognitive mechanisms by which it might do this. Their table 1:

Once you jettison the tired old reason-emotion dichotomy it frees you up to have much more interesting thoughts about the role of emotions in decision making. It also has the benefit that you won't be tempted to dismiss people who express emotions as irrational, which both delegitimises their opinions and falsely relieves you of responsibility for trying to argue with them.

The idea that emotions are not reason responsive allows us to dismiss people (ie women ) who are emotional as "irrational" AND justifies not trying to change their mind (Gordon-Smith, 2019, p193, briefly reviewed in RP#4)

References

Bortolotti, L. (2014). Irrationality. John Wiley & Sons.

Damasio, A. R. (2006). Descartes' Error. Random House.

Pfister, H. R., & Böhm, G. (2008). The multiplicity of emotions: A framework of emotional functions in decision making. Judgment and decision making, 3(1), 5.

If you enjoy the newsletter, please consider forwarding it, or telling people about it by sharing this link https://tomstafford.substack.com and if you can complete or complement any of my half thoughts, please hit reply and get in touch

LINK: Why Don’t We Just Ban Targeted Advertising?

Giled Edelman, in Wired, says ‘From protecting privacy to saving the free press, it may be the single best way to fix the internet.’. I like the piece because it doesn’t just make the case for banning targeted advertising, but tried to imagine the future where such advertising was banned. It was good on twitter to be corrected by people who know more about advertising than me - apparently the article’s citation of evidence that targeting is ineffective is selective. There is more positive than negative evidence that targeted advertising is effective, or at least that advertisers believe it to be effective. Not that advertiser belief is the bottom line, but they are strongly motivated not to waste their money.

Work by Garrett Johnson is the place to start if you want to cultivate an evidence-informed view of this.

Believing targeted advertising is ineffective is tempting, because it simplifies the moral calculus: societal costs of ads don’t need to be balanced against any benefits, societal, commercial or personal.

But if targeting is effective, you can still ask if the benefits outweigh the costs. Edelman’s article makes a strong case that ad targeting puts an incentive on harvesting user data, that then is passed to data brokers and from there leaks to insurance companies, potential employers and the state. Your mileage may vary, but there’s a question about how worried we should be about this.

You can also ask if targeting is a legitimate persuasion technique. The Centre for Data Ethics has just published a report on Public Attitudes Towards Online Targeting. There’s a lot to digest there, but it suggests that the (UK) public are concerned about ad targeting, both in terms of a capacity to undermine autonomy by changing preferences directly, to influence by long term exposure and the effect on vulnerable people (e.g. those with gambling addictions).

Related, an old post of mine: Facebook’s persuasion architecture and human reason

AND FINALLY

And Other Stories is a small publisher based in Sheffield, England, which specialises in translations and literary fiction. Not only do they publish some great books, but they offer subscriptions, which means you directly fund the production of new work and then receive books you’ve helped fund in the post. There are two extra reasons you should subscribe:

In response to the current crisis, And Other Stories are pledging 20% of the value of new subscriptions will go the local bookshop of your choice, so you are supporting authors, publishers, and book sellers in your local economy.

If you subscribe now, you’ll get my mate Rachel’s second novel “What You Could Have Won” in the August package, before it is published in October. Rachel is a recovering neuroscientist who has been writing since 2005. I read an early chapter of What You Could Have Won and it is sure to be brilliantly intense and intensely brilliant.

Full disclosure, obviously I am well disposed to all bookish people, and Rachel and And Other Stories in particular are my pals, but you know it makes sense