The Ideological Turing Test

Do you truly understand those you disagree with?

More new work I was involved with. I’m really proud of this work, and hope you enjoy the brief summary given here.

It’s a simple idea. Before you disagree with someone, prove you understand what they are arguing.

It’s a basic piece of intellectual hygiene, sadly more and more required. Social media thrives on taking people’s statements out of context. There is an ever-ready carnival of the commentariat who harvest kudos from their in-crowd by dunking on common enemies. Amidst all this sound and fury, it would be easy to think someone else a fool, scoffing at what you think they believe, without having an accurate understanding of what they are actually saying.

This idea was given the name The Ideological Turing Test by Bryan Caplan. The original Turing Test was proposed to distinguish human from artificial intelligence - if a computer can masquerade so that a human judge accepts it as human, then we can say it has met some standard of human intelligence.

The Ideological Turing Test puts a spin on this idea. Understanding, like intelligence, is a complex object, hard to define or prove. So, let’s declare that if you can masquerade as one of your ideological opponents, so that one of those opponents endorses the reasons you give for their position, then we can say you have met a standard of understanding.

This is the Ideological Turing Test: can you express reasons for positions you don’t actually believe, but in a way that people you disagree with recognise and say “Yes, that’s what I believe, and why”.

A few years ago, I was involved in a project that provided an opportunity to build on this idea of the Ideological Turing Test. Opening Up Minds was funded by the EPSRC and led by Paul Piwek, of the Open University. The project asked if we could use large language models to help people explore the argumentative structure of their own beliefs, and beliefs they disagreed with. As part of this, we wanted a measure of understanding, something with a bit more rigour than just asking people “Do you have a good understanding of the reasons given by people who disagree with you on this issue?”.

We were lucky enough to be joined on the project by the brilliant Lotty Brand, who led the development of the Ideological Turing Test measure. Our report of this work has just been published by the journal Cognitive Science.

The contribution made here is to move from the mere idea of the Ideological Turing Test to show how it can be practically measured.

To do this we picked three topics which we were confident would let us recruit UK adults with opposing views - Brexit, Veganism and Vaccinations. Brexit famously split the country in 2016. The topic of vaccination is not evenly split, but in 2021 when we started the project, it seemed important to understand the minority who refused vaccination. The topic of Veganism provides a third contrast, it is neither evenly split (most people aren’t vegan), nor is it politicised in the same way as the Brexit and Vaccination topics.

We came to realise that the project, as well as allowing us some insight into differences between individuals in their understanding, would also allow us insight into the groups which took different positions on these debates, and the argumentative terrain they occupied. It could be possible, for example, that those who were pro-vaccination wouldn’t understand those who are anti-vaccination1 , but the anti-vaccination individuals would better understand those who were pro-vaccination, since pro-vaccination views got more publicity. Or it could be possible that people on one side of the veganism debate all have similar reasons for their position, but people on the other side subscribed to a more diverse set of reasons. Or, also, that people understand each other across some of the divides we looked at, but on something as acrimonious as Brexit there would be a gulf of mutual misunderstanding.

I’ll spare you the details of the method - they are in the paper - but I’m really happy with the rigour we were able to bring to this project. To collect our data we had to identify people who subscribed to opposing positions on the three topics then ask them to provide arguments for what they believed, and ask them to provide the arguments someone who disagreed with them might provide. Specifically, assuming we recruited someone who believed a position we’ll call X, we asked:

“Imagine you are chatting with someone who is anti-X. What might this person say to you? Please provide THREE reasons that they might give for being anti-X”

We then asked people from both sides of each topic to rate the arguments according to how strongly they agreed or disagreed with them. When an argument comes from someone who disagrees with the position, and is rated by someone who agrees with it, this is the canonical Ideological Turing Test - can someone get the arguments they provide endorsed by an ideological opponent, so they, in effect say, “Yes, I agree with that.” The other combinations: someone providing arguments in favour of the position they hold, or rating arguments in favour of a position they hold, provide control comparisons. You’ll see later why these were important.

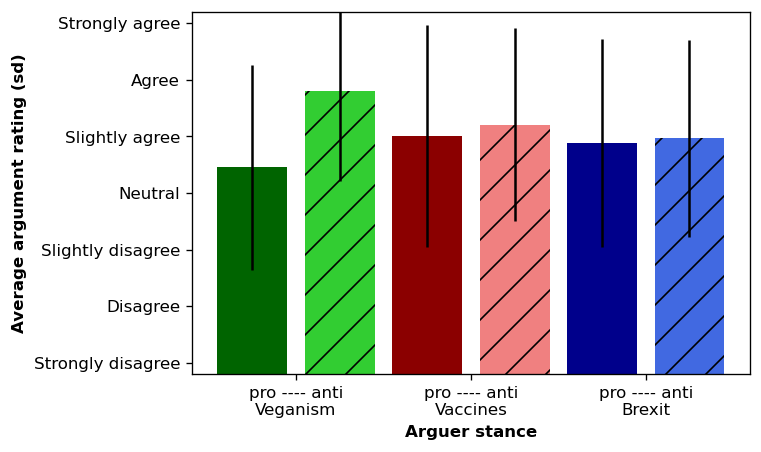

Here’s a graph, redrawn from the data available in the paper, showing how successful people from different positions on the different topics were at producing arguments which their ideological opponents endorsed.

You can see the different topics are in different colours and the pro and anti positions in clear or hatched bars. The scores relate to arguments which are the opposite to the arguer stance (because this is the Ideological Turing Test), so for example the leftmost bar shows data for arguments against veganism provided by those who are pro veganism (i.e. vegans), rated by those who are not vegans.

For me, the main message of this is the general level of high scoring. On all topics, most arguments provided were endorsed somewhat, and many to a high degree. This means that people across both sides of all three positions were able to articulate the reasons held by those they disagreed with. Although mutual misunderstanding may occur, for our sample on these topics it seemed to be the exception rather than the rule (looking at the actual arguments - which are shared alongside the paper - there are a few people who submitted arguments unlikely to get strong endorsement, things like “I am pro-Brexit because I am an idiot”, but these are rare).

The graph also suggests a curious finding, that people from both sides of the Brexit and Vaccine topics seem equally skilled, able to produce arguments endorsed at the same rate by their opponents. The symmetry looks not to hold for Veganism. The non-vegans obtain higher ratings, able to produce pro-vegan arguments which are strongly endorsed by vegans, but the reverse doesn’t hold, vegans are not able to produce reasons which are rated highly by non-vegans.

You could be tricked into thinking that this is a blindspot on behalf of vegans but you’d be wrong. The asymmetry is actually a product of the argumentative space, which becomes visible when we use the control data we collected.

The graph above shows the ratings of the arguments on an absolute scale - how strongly did people agree or disagree with them. The key to understanding the veganism topic is to incorporate information on how hard the task is for different positions. The fact is, when we looked at the data, we found that everyone - vegans and non-vegans - tended to rate the arguments in favour of veganism highly. Non-vegans might not have vegan diets, but they endorsed the arguments. In contrast, everyone - both vegans and non-vegans - had a harder time producing arguments against being vegan. For the Ideological Turing Test this meant that vegans had a harder task - the structure of the argumentative space means arguments against a vegan diet are harder to articulate and/or people feel less inclined to strongly endorse them2

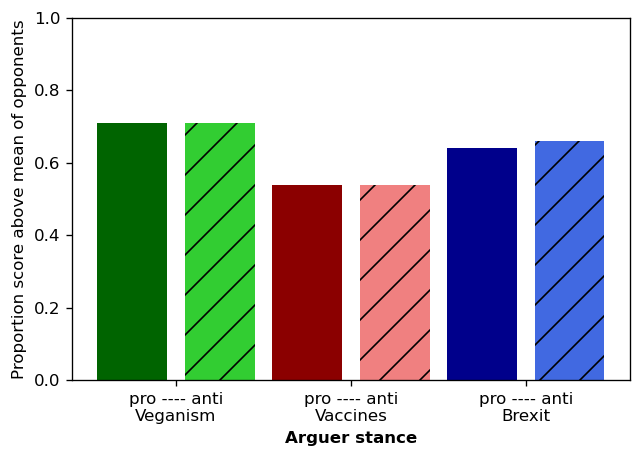

To make a formal comparison, we can replot the same data but using a relative criterio rather than the absolute criterion. Here’s the plot, now with the vertical axis showing the proportion of arguments that were rated higher than the mean in the control condition (arguments for a position, provided by those who truly believed that position, rated by others who also held that position).

Now we get a comparison which is normalised for difficulty. Across all three topics, people on both sides are just as able to provide relatively strong arguments for the opposing position.

The relative standard also emphasises the difference between topics. Now veganism stands out as the topic with the highest mutual understanding. Vaccines, not Brexit, is the worst.

I don’t want to overclaim too much on the specific results here. There’s an issue of temporal validity here - we collected these data March - May 2022, from an online sample of UK adults. Attitudes to all these topics will have shifted since, and will be different for different samples.

Instead, the two strongest claims I want to make are these:

We show it is possible to operationalise the idea of an Ideological Turing Test, and so produce a behavioural measure of argument understanding. The advantage of a behavioural measure is that - unlike a self-report of open-mindedness, where you tick a box to say something like “I am very aware of different perspectives” - you cannot fake performance on the Ideological Turing Test. If you understand arguments for the opposing position you can produce them; if you believe you understand them, but cannot produce them, then we can confidently say you don’t really understand.

There are high levels of mutual understanding across these three topics. Whether you are surprised or not will depend on your prior expectations, but these are topics which are known for producing some antagonism and, at worst, accusations of irrationality or immorality across the aisle. That may exist, but these results suggest that there is also a centre of mutual comprehension and (not discussed in this post, but it is in the paper) acceptance that people can disagree and still be rational and moral.

We’ve produced an interactive app which lets you explore the arguments (and the ratings they’ve received), please enjoy: https://sheffield-university.shinyapps.io/OuMshiny/

The full paper is

Brand, C. O., Brady, D., & Stafford, T. (in press). The Ideological Turing Test: a behavioural measure of open-mindedness and perspective-taking. Cognitive Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.70126

Link for the Opening Up Minds project this was part of.

Slides for a talk on this I gave over the summer: “Do we truly understand those we disagree with, and how could we test this? The Ideological Turing test”, Evolution and Social Cognition lab, Institut Jean Nicod, Paris.

I’m writing more for Reasonable People while on my career break, giving me more time to finish up projects I’m particularly proud of, like this one, and to write about them for the newsletter. Upgrade to a paid subscription to encourage more of this.

Keep reading for more on what I’ve been reading on social media, fact-checking and reasoning.

Both Democrats and Republicans can pass the Ideological Turing Test

After we’d collected our data, but before publication, Adam Mastroianni of Experimental History published his report Both Democrats and Republicans can pass the Ideological Turing Test.

This study used a single topic with an even split (at least among US adults) - US politics. Like us, Adam and his team’s results showed that people from both sides were equally good at passing the Ideological Turing Test. At various points he construes this as being equally bad at discriminating true (ideology aligned) from false (ideological faking) statements. Since the difficulty of the task is a direct effect of the ability of people to produce convincing “pretend” statements I think that construal is unnecessarily negative. Regardless, the implication is similarly positive:

These results also suggest that America’s political difficulties aren’t simply one big misunderstanding. If one or both sides couldn’t pass the ITT, that would be an obvious place to start trying to fix things—it’s hard to run a country together when you’re dealing with a caricature of your opponents. When both sides sail through the ITT no problem, though, maybe that means Republicans and Democrats have substantive disagreements and they both know it.

Link: Both Democrats and Republicans can pass the Ideological Turing Test (substack) and PDF

Google cuts funding to Full Fact.

UK fact-checkers Full Fact announced this on their mailing list on Friday. Here’s how they reported it:

Google has ended its support for Full Fact. The company has been one of our biggest funders over the last three years, helping us build some of the best AI tools for fact checking in the world.

But things have now changed abruptly: Full Fact received over £1m from Google last year, either directly or via funds the company supports. These have all either not been renewed, or have been cut altogether.

We think Google’s decisions, and those of other big US tech companies, are influenced by the perceived need to please the current US administration, feeding a harmful new narrative that attacks fact checking and all it stands for.

Full Fact will always be clear: verifiable facts matter and the big internet companies have responsibilities when it comes to curtailing the spread of harmful misinformation. If you agree, please support Full Fact today. We add to debate, we don’t restrict it. We promote more speech, not less.

Link: Donate to Full Fact

New User Trends on Wikipedia

In what I see as related news, Wikimedia report that AI is taking human traffic away from Wikipedia. This is happening because other platforms (such as Google search) use Wikipedia to generate summaries of information and deliver them directly to users. Compared to last year, visitors are down 8% at Wikipedia.

You might think this isn’t so much of a problem, but at the same time - and caused by the same industry - the majority of the bandwidth to the wikipedia sites, which wikipedia has to pay to support, is being used up by automated processes, scraping content to train AI models.

This is how Wikimedia put it

25 years since its creation, Wikipedia’s human knowledge is more valuable to the world than ever before. Our vision is for a future where everyone can participate in knowledge creation and sharing – a future that is possible when everyone uses the free knowledge ecosystem responsibly. As we call upon everyone to support our knowledge platforms in old and new ways, we are optimistic that Wikipedia will be here, ensuring the internet provides free, accurate, human knowledge, for generations to come.

The general pattern is of commercial tech companies extracting from the knowledge commons, happy to use it, and allow it to degrade, without providing support from their voluminous coffers.

Link: New User Trends on Wikipedia

How to tell if a social media account is monetized

From our friends at Indicator. This seems incredibly important in terms of interactions online. So much inauthentic behaviour is because people are making money from outrage, being able to tell which accounts are in it for the £££ is a vital part of intellectual self-defence.

Link: How to tell if a social media account is monetized

….And finally

“More of whatever this is”, says @samw

END

Comments? Feedback? Arguments you disagree with but I might endorse? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

This is “anti-vaccination” in lower case. We recruited people who had refused or intended to refuse the covid-vaccine. This did not mean they identified as “Anti-Vaxx”

We could speculate as to why this is. Maybe, because veganism is a minority position, people haven’t made the effort to elaborate the arguments against it.

The most outspoken people in politics and online do not behave as they could pass an ideological Turing test. That is what makes these results surprising.

Maybe the hard part - what leads to misunderstanding, isnt so much being able to restate what other people argue as it is being able to explain why they view those arguements as legitimate. For instance, I may understand that in Afghanistan it is normative to kill a daughter that disgraces the family because she was raped. But if I cannot grasp why those arguements are excepted there in grounded terms, even though I can state those arguements word of word, then it leads me to believe I do not understand their culture.