Gambling with research quality

How you get 244 different ways to measure performance on the same test of decision making. And what it means for the reliability of behavioural science

A new study has been released, and it beautifully illustrates a fundamental issue in making behavioural science reliable and interpretable. Possibly it illustrates, a fundamental issue with making any science reliable and interpretable.

On Friday I was invited to talk at an event at the University of Liverpool “Does AI threaten research integrity?”, co-sponsored by the terrific UK Reproducibility Network (UKRN). For my talk I wanted to start with considering how various actors in the research system define research integrity, and to share my take on the ‘special sauce’ that defines UKRN’s approach here.

All research has a problem with reproducibility, broadly defined. Some fields, like psychology and behavioural science, have a well publicised problem with phenomena which are reported, nay celebrated, but are just not real1. Other fields have less of an issue with that. In civil engineering, I imagine, if researchers say that a particular method will keep a bridge from falling down the world finds out pretty quick how right they are. Still, in those fields, there are still a host of issues about the reliability of published research, the ability of researchers elsewhere in academia or industry to understand and audit what was done, and for anyone (including the original researchers) to repeat it, scale it and/or translate it into new contexts.

Defined like this, reproducibility applies across all research endeavours. Whether you are researching more efficient manufacturing for widgets or marriage networks in Medieval royalty, you still need to be able to discover the truth and effectively share it, and that means sharing in a way that reliably signals credibility, as well as transmitting the raw result. You don’t have to buy into the idea that there is a reproducibility ‘crisis’ in your field to see that increasing reproducibility is needed.

The UKRN, and the wider global network of Reproducibility Networks, play a unique role here, coordinating researchers themselves to articulate and bring about improvements in research quality. This, I argue, is an essential ingredient in the special sauce of the UKRN: it is focused on ‘research improvement’, not a more narrowly defined ‘research integrity’. We could argue the semantics, but in many contexts research integrity has been captured by the governance issues of dealing with research fraud and other severe malpractice.

Those things are bad, but an essential insight is that you don’t need to be actively trying to make dishonest, unreliable or irreproducible research - you get these things for free simply because honesty, reliability and reproducibility are unreasonably hard to achieve.

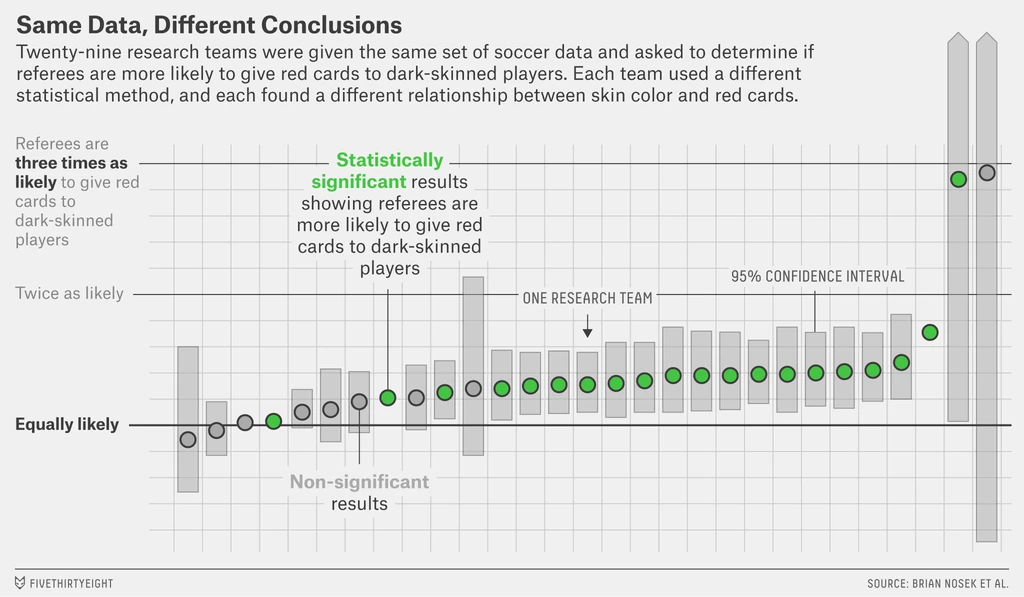

This was brought home to me by the “Many Analysts” study I was involved with, in which 29 research teams were all given the same data and the same research question. Lining up each team’s results there were not just 29 different answers, but significant range - the answers varied from saying that the effect was negative (left of the figure below), that there was no effect, to there was a significant positive effect (right of the figure).

More than this, each team used a different statistical model, and followed a different data preprocessing procedure before estimating the effect.

The moral was well expressed by the paper: “significant variation in the results of analyses of complex data may be difficult to avoid, even by experts with honest intentions.”

Most research has just one analysis team and reports a single, best, estimate. If you do this, how do you know if you are an outlier, like the teams at the extreme ends, or somewhere the middle. You can’t!

The implications for the research literature are profound. Honest, dedicated, skilled researchers may investigate a topic and come to opposite conclusions because of variation between how they conduct their analysis - never mind the variations in how the data to be analysed is collected.

§

Now a new report by Annika Külpmann and colleagues - Methodological Flexibility in the Iowa Gambling Task Undermines Interpretability: A Meta-method Review - has been published, which gives another glimpse of just how deep this problem can be.

The Iowa Gambling Task is a classic test of decision making ability. It is used widely in medical research, but also in healthy populations to look at differences in decision making. It’s the kind of task every psychology student will have heard of. In the Task you are presented with four decks of cards, with each card delivering a reward or penalty. You are asked to draw cards from the decks, trying to accumulate as many points as possible. Unbeknown to participants, for two of the decks the average payout is negative - while most cards might give out a reward, these decks also contain penalty cards which over time outweigh any benefit of drawing from these decks. The original designers of the task thought that if you had intact frontal lobe function, you should learn to avoid the “bad” decks and prefer to choose from the “good” decks.

The Iowa Gambling Task has been used in literally thousands of research studies, which is why the result of the Külpmann et al review is so surprising. We hope that the more popular methods in any field will be the most reliable. Not so.

Külpmann et al started by picking 100 studies at random from a very long list of published studies. They found that there were hundreds of different versions of ‘The’ Iowa Gambling Task. Different research teams varied the instructions given to participants, the size and frequency of rewards and punishments, the order of the cards in the decks, the number of trials, and many other things. So extreme was this variation that Külpmann et al say the Iowa Gambling Task should be considered a “franchise”, not a single task, something that is undergoing constant adaptation for different purposes.

Obviously, if the Task is actually many different Tasks this makes it hard to draw conclusions across different studies. If studies have different findings it could just be because they involved different tasks and called them the same thing. Compounding this, Külpmann et al found that none of the meta-analyses they looked at - studies which are meant to synthesise across the published literature - used procedural variation as a criterion for including or excluding studies in their review. The meta-analyses assumed all these procedural variations didn’t matter. A big assumption!

Adding to this mess, Külpmann et al found that many studies didn’t even include enough detail to know exactly how they had varied the task when it was implemented - this was true for 65% of clinical research papers which used the task. Yes, 2/3rds of studies which reported findings using some variation of task didn’t contain the information which would let anyone else repeat what they did.

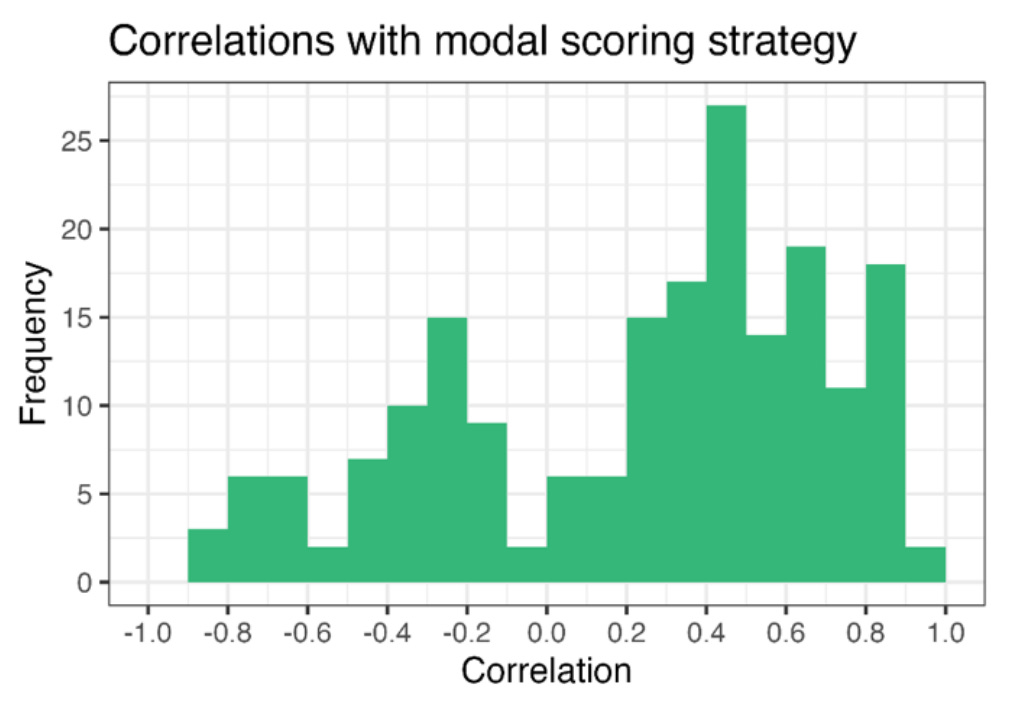

The most damning part of the Külpmann et al report concerns their analysis of different scoring methods. Even for researchers running identical versions of the Task, there is still flexibility in how you calculate performance on the task. You can count the choices from good decks vs bad decks, or count the points. You can look at all choices, or just the choices in the second half, or you could calculate a learning curve over successive trials. When you have a score, you can transform it in various ways to control its statistical properties (imposing maximum or minimums for example). Or you can do all of these things in some combination.

Incredibly, Külpmann et al found, across 100 studies, 244 different scoring methods reported. Over 200 of these were mathematically distinct.2 This incredible variety is a playground for individual researchers to fish around for a scoring system that ‘performs better’ - in other words, which gives them the results they hoped to get from running the task.

If the different procedural variants and the different scoring methods all gave very similar results, this variation wouldn’t matter. This was not the case.

By using a large, open, dataset of Iowa Gambling Task data Külpmann et al were able to run these 200+ different scoring methods on the same data. They found that choice of scoring method could vary a result in any direction, to any extent. Here is their plot of the correlation of the different methods against the the single most common (modal) method:

The correlations (x-axis) go from near 1 (perfectly matches the modal method), through 0 (completely independent of the modal method) to near -1 (the perfect opposite of the modal method). Yes, that means that you could - by careful choice of an existing scoring method from the literature - find any effect, or nothing, or the reverse of any effect you choose.

This is bonkers. It’s like if you went to see a doctor and they had thermometer which, depending on details which they won’t reveal to you, could tell you your temperature perfectly, give you a random result, or be the opposite of correct temperature, and the doctor themselves didn’t know which one it was.

The situation is so extreme as to be farcical.

§

The solutions to this mess are well rehearsed: transparent reporting, data sharing, protocol standardisation, measurement validation (see Flake and Fried, 2020, for example).

The worry is that if it is this bad under this particular empirical rock, it might be just as bad in other parts of behavioural science, or beyond.

The lesson of this, and many other studies, is that good intentions are not enough to deliver consistency and validity. Research studies are complex objects, complex objects where the details matter. We can’t rely on academic conventions for carrying out and reporting research to deliver credibility and reliability at the population scale. This is the reproducibility problem

And if you think your own favourite research area is problem free, ask yourself how you know that, and how systematically people have looked.

This newsletter is free for everyone to read and always will be. To support my writing you can upgrade to a paid subscription (more on why here)

Keep reading for the references and other things I’ve been thinking about

§

References

The Iowa Gambling Task study:

Külpmann, A. I., Ries, J., Hussey, I., & Elson, M. (2026, January 24). Methodological Flexibility in the Iowa Gambling Task Undermines Interpretability: A Meta-method Review. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/4g3vr_v1

The Many Analysts team study:

Silberzahn, R. et al (2018). Many analysts, one dataset: Making transparent how variations in analytical choices affect results. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(3), 337-356.

More on measurement validity:

Flake, J. K., & Fried, E. I. (2020). Measurement schmeasurement: Questionable measurement practices and how to avoid them. Advances in methods and practices in psychological science, 3(4), 456-465.

You can find my slides from the event in Liverpool here (reading the slides may be the ideal way of consuming the talk, since you get full references to all the things I talked about, but with none of my commentary). Thanks to the organisers for inviting me and to everyone who attended in person and online.

Grokked

Last time I reported some research on the Wikipedia-alternative, Grokipedia. This story illustrates another motivation a billionaire might have for building an alternative encyclopedia - so as to be upstream of the information LLMs rely on.

The Guardian 2026-01-24: Latest ChatGPT model uses Elon Musk’s Grokipedia as source, tests reveal.

Although there are reports that propaganda sites generally just fill information gaps, where conventional media haven’t captured the keyword space, rather than successfully usurp mainstream media:

Kate Starbird is now on Substack

And anyone who cares about making sense of our information environment should probably follow her:

Henry Farrell: Davos is a rational ritual

Henry Farrell analyses Davos as a stage on which the powerful coordinate over the creation of common knowledge.

Link: Davos is a rational ritual

Lord of the Rings, redux

Lols at this meme riffing of the well-known sycophancy of commercial language models:

Casey Newton: What a big study of teens says about social media — and what it can’t

Casey argues that we don’t need a study to know that the online environment is designed to be exploitative of our worse instincts, and that big tech has been persistently, culpably, shamefully negligent in protecting younger users:

"The next time you go to Las Vegas, you’ll notice that there are no 13-year-olds in the casinos. The reason is not because a series of longitudinal studies proved to the satisfaction of the gaming industry that gambling causes anxiety and depression. Rather, there are no 13-year-olds in casinos because we know that the environment is designed to exploit them."

Link: What a big study of teens says about social media — and what it can’t

Daisy Christodoulou: How to write a good rubric (for humans and AI)

Daisy Christodoulou is lucid on the perils of designing a reward strategy [in assignment marking terms, a rubric], with too much of a negative focus. To avoid perverse incentives you need to include what you actively want, not just what you will punish, and you need to give those who do the assessment some discretion. She shows how this applies - but doesn't only apply - to education.

Link: How to write a good rubric (for humans and AI)

… And finally

END

Comments? Feedback? Pick a card, any card? I am tom@idiolect.org.uk and on Mastodon at @tomstafford@mastodon.online

At this point, it isn’t clear of the ‘reproducibility crisis’ in psychology, which kicked off from roughly 2010 onwards, was a product of psychologists being particularly self-aware, or because the state of psychological science itself was a particularly egregious bin-fire.

Precisely, the authors treated two methods as distinct if they weren’t simple linear transformations of each other.

A big part of the problem is that classical hypothesis testing promises much more than it can deliver. "Rejecting the null with 99 per cent confidence", even with good practice, means something like "there's more than random noise here, and we should look into it". If you start with a broadly Bayesian view of the world, you can restate this as "I've adjusted my probabilities to give a bit a more support to the hypothesis I wanted to test".